Merce Cunningham, Barbican Theatre, London <br>Richard Alston, Sadler's Wells, London</br>

Merce Cunningham has been making fresh, daring work for half a century ... and he's not done yet

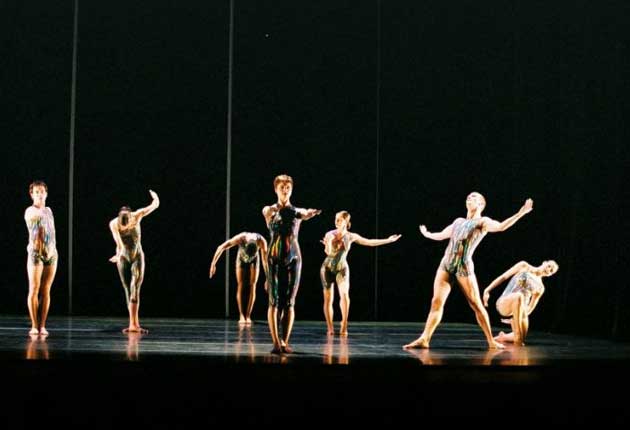

Astonishing as it is to find an 89-year-old launching Britain's premier contemporary dance festival in person, what's more astonishing is that Merce Cunningham has been ploughing the same unswerving furrow all his life. Dwight Eisenhower was in the White House when the opening work of this Barbican show first saw the light. Yet thanks to its purity of concept and dazzling execution, it looks as fresh and daring as anything made since. Crises (1960) sets out the premise that underpins every one of Cunningham's 200 works – that music and dance can happily be at the same party without being introduced. In this piece the dislocation verges on comic, as Conlon Nancarrow's crazy studies for pianola – created by randomly cut-and-pasting ragtime piano rolls – rub along with steps that are puritanically severe, tottering on high-arched feet or balancing serenely like hovering gulls.

Without the programme booklet, I would have been stumped as to the chronology of the three works on this bill, not least since the newest, Xover (2007) is a tribute to two Cunningham collaborators, both now dead. What's more, the John Cage score consists of two 1958 compositions run simultaneously, layering electronic swooshes with croaked human speech, rook calls and dog barks. Rauschenberg's backdrop is an image of roadworks, before which Cunningham's white-unitarded dancers move in discrete bubbles of beauty and calm. The strength and control this calls for are extreme.

By eschewing fashion, or rather, by setting his own, Cunningham has made his work timeless. Yet he's also been consistently ahead of the game, and, in 1999, was among the first to experiment with digitally generated design. The result, Biped, is one of his most glamorous creations. A futuristic scaffold of light-beams frames the choreography, and digital avatars of dancers – sometimes resembling draughtsman's scribble, at other times wreaths of smoke – magically cavort across a front gauze screen. Although the piece is too long by half, and the looping lusciousness of Gavin Bryars's electric-guitar score palls too soon, Biped remains a thing of jaw-dropping wonder. Ravishing.

Richard Alston, once a Cunningham acolyte, now a mentor himself to countless budding dancers, took up the Dance Umbrella baton at Sadler's Wells with a show meant to celebrate his 40 years of dance-making and 60th year on the planet.

The retrospective element, titled The Men in My Life, contained the evening's best moments: the seraphic Jason Piper reprising a courtly solo to Handel's Water Music, Jonathan Goddard gaunt and impressive in Dutiful Ducks, created long ago for a young Michael Clark. In a way, the effect was more elegiac than celebratory. It's hard to be reminded of things that are lost and gone.

Of the two new works, Shuffle It Right won hands down: a deft, larky response to old Hoagy Carmichael records. Again, it was Goddard whose toes twinkled brightest. Happy birthday, Richard. Here's to many more.

Richard Alston: Cambridge Arts Theatre (01223 503333) 7-8 Oct, and touring

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies