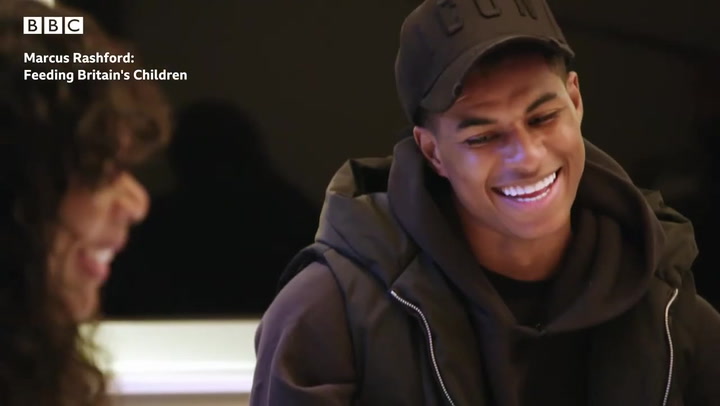

Marcus Rashford: Feeding Britain’s Children review – Footballer’s remarkable year is chronicled in moving documentary

In this new film about the the 23-year-old’s campaign against child poverty, Rashford’s mother Mel also emerges as a driving force for good

Marcus Rashford knows a goal when he sees one. The Manchester United and England forward could hardly have had a better year if he had personally developed the coronavirus vaccine. On the pitch he has been prolific: until the weekend, he was his club’s top scorer in all competitions this season, a tally that includes his first hat-trick. Even more delightfully, he’s also been curling screamers past the Tories all year. His campaigning on free school meals, supporting food charities and other groups, has forced Boris Johnson & Co to repeatedly backtrack on their food policy for children. In October, Rashford was awarded an MBE. To cap it off, on Sunday night he received an “Expert Panel Special Award” at the BBC’s Sports Personality of the Year.

For this hour-long behind-the-scenes documentary, Marcus Rashford: Feeding Britain’s Children (BBC One), cameras followed the 23-year-old on his remarkable year. He has been campaigning in a more low-key way for a few years, but things took off in March, when he started working with the charity FareShare. Then in June, when he wrote an open letter to MPs about free school meals, Rashford suddenly became a household name as a campaigner as well as a sportsman.

The government had initially said it would not continue to provide free school meals during the summer holidays, which would have deprived about 200,000 children in a year already disrupted by the pandemic. Rashford wrote movingly about his own childhood in Wythenshawe. Despite the best efforts of his mother, Mel, he was only able to make it as a footballer thanks to an extended support network. “The system was not built for families like mine to succeed, regardless of how hard my mum worked,” Rashford wrote. “As a family we relied on breakfast clubs, free school meals and the kind actions of neighbours and coaches.”

The letter was shared widely on social media and reported on by every newspaper. Two days later, the government reversed its decision. In late October, he did it again, getting more than a million signatures for a petition urging the government to provide more support over the winter. Again the government resisted, and again they were forced into a U-turn. One of the highlights of the film is Rashford taking a call from the chastened Johnson, who tells him he will be agreeing to his demands.

The film, which feels shaggy at times, isn’t quite up to the standards of the brilliant story. For anyone who’s been half-awake, the events will not be news, so the interest is in learning more about this remarkably level-headed and driven young man, and putting his work in context. We get glimpses of Rashford as he visits his old school and hangs out with this brothers, but like most modern footballers he is wary in a world where critics pounce on the slightest misstep.

He obviously has a smart team around him, especially his personal publicist, Kelly, who joins him on his conference calls with supermarket CEOs and food strategists, helping articulate his vision. Between the lines there is a rare positive story about the power of social media, which lets a young working-class black man bypass traditional intermediaries to take the fight directly to government. Inevitably, his actions provoke a backlash from the usual sources: Conservatives accuse him of “virtue signalling”, and Tory MPs whine about “personal responsibility” and costs. Their arguments would always be mean-spirited, but are borderline ghoulish when the government has been dishing out untold billions in other forms of coronavirus support. The issue of child food poverty hasn’t gone away; Unicef announced last week that it is helping to feed British children for the first time its history.

One of the most moving moments in the film is when Mel talks about her struggles when her children were young. She’s the other star of the show, radiantly proud of her son but clearly still embarrassed that she couldn’t always provide as she would have liked.

“In my eyes, a lot of the work is my mum's work,” Rashford says. “She’s the one who brought me up with these morals and expectations.” The country should be proud of his work, and embarrassed that it’s necessary.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies