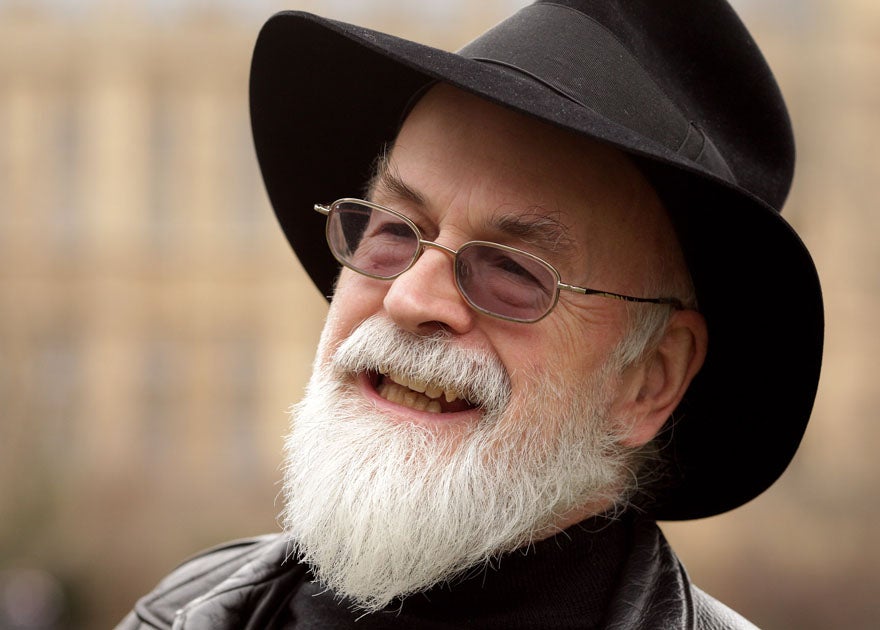

The Weekend's TV: Genius of Britain, Sun, Channel 4<br/>Terry Pratchett's Going Postal, Sun, Sky1

A fine appliance of science

Philosophy will clip an angel's wings," said Keats. But Keats was wrong, said David Attenborough at the beginning of Genius of Britain – well, implicitly at least: "The world is full of wonders," he declared, "but they become more wonderful when science looks at them." Take that, Keats.

Yes, science might have emptied "the haunted air and gnomed mine", but it has replaced the ghosts and the gnomes with something better. Oddly, though, this robust and rational defence of science – part of a distinctly defensive overture to Channel 4's celebration of British scientific brilliance – came dressed in the rhetoric of magic and the supernatural. You'll know the kind of thing from countless television programmes: ethereal tinkling on the soundtrack and a lot of optical magic for the landscape shots, flaring the light into the otherworldly and the numinous. It's the standard shorthand for there being more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy. Tellingly it was pretty similar to the idiom used for the opening of Terry Pratchett's Going Postal, Sky's lavish adaptation of one of Pratchett's gleefully otherworldly Discworld novels.

I take it this was a clue to the defensiveness. "We want to set the record straight," Stephen Hawking said at the beginning, "and put science back on the map." It was news to me that it had ever been taken off, but what you sensed at work here was a backlash against a backlash – against a fundamentalist caricature of science as a drab failure of imagination. If you want awe and the marvellous, the style said, science can give it to you. Enlisted in the cause, as if to match up with the quintet of pioneering British scientists profiled in the programme, was a relay team of distinguished scientific presenters: Attenborough came out of the blocks with a little section on Christopher Wren's passion for astronomy, passed the baton to Richard Dawkins, who used his stretch to fill us in on Robert Hooke and early microscopy, before a clean handover to James Dyson, appropriately on hand to talk about Robert Boyle's experiments with an early vacuum pump.

It was full of fascinating detail, though I'm not convinced that all of their anecdotes will have successfully countered the prejudice that science privileges hard fact over morality and feeling. Wren, Attenborough told us, had scotched the widespread belief that the spleen was essential to life by tying down a spaniel, performing a crude splenectomy, and then sewing the wretched animal up again. The dog survived, astonishingly – but I think Wren's reputation with the dog-loving British public may have taken a bit of a knock. At least Newton used himself as a guinea pig, notoriously probing around behind his own eyeball with an ivory bodkin in order to explore the properties of light. Then again, Newton wasn't exactly a moral paragon either; it's said that one reason there are no surviving portraits of Robert Hooke is because Newton was so consumed by his rivalry with him that he had them all destroyed when he took over at the Royal Society. To weigh against that, of course, you have Principia Mathematica, which Jim Al-Khalili described as "the greatest book ever written in history" in another little dig at scriptural dogmatists of another kind.

The cosmology of Going Postal is perhaps best described as pre-Newtonian. The Earth is flat and rests on the back of three humungous elephants, which in turn rest on the back of a giant turtle. This, as Terry Pratchett devotees will know, is Discworld, an extensively chronicled alternative universe in which the knowing joke is one of the fundamental physical forces. Those who aren't Pratchett devotees might be pleasantly surprised by Going Postal, which is so nicely done that it makes a proselytising case for the author's distinctive imagination. Richard Coyle plays Moist von Lipwig, a con-man and fraudster who is saved from the gallows to bring a bit of healthy competition back to the communications industry in Ankh-Morpork. Charles Dance's Lord Vetinari invites him to revitalise the derelict postal system in order to give consumers an alternative to a kind of steampunk telegraphy system, run with monopolistic greed by the villainous Reacher Gilt.

Moist has no intention of doing any such thing, particularly since he soon learns that all his predecessors have died trying. But as he tries to raise enough funds to flee, he inadvertently invents postage stamps – and begins to be haunted by the consequences of his former frauds. He also has the problem of getting away from his probation officer, a giant golem called Mr Pump, who eventually brings him into contact with the love interest in the piece, a young woman who runs a golem rights consciousness-raising group. It looks terrific and is full of good jokes, including a running gag about Stanley, one of the junior postal clerks, who is an obsessive pin collector. In an attempt to make small talk with him, Moist mentions that he's seen Pins Monthly on the newsstands. "That rag is for hobbyists," hisses Stanley. "True pinheads only read Total Pins." There are appropriately scary villains, some lovely special effects, including a tsunami of undelivered letters that pursues Moist through the corridors of the old Post Office, and just enough real feeling to make you care about what happens next. One of the opening credits read "Mucked about by Terry Pratchett", but neither he, nor they, mucked it up.

t.sutcliffe@independent.co.uk

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies