How deep is the ocean and what’s at 3,900 metres?

The US Coast Guard is leading the search for a small vessel off the coast of Canada.

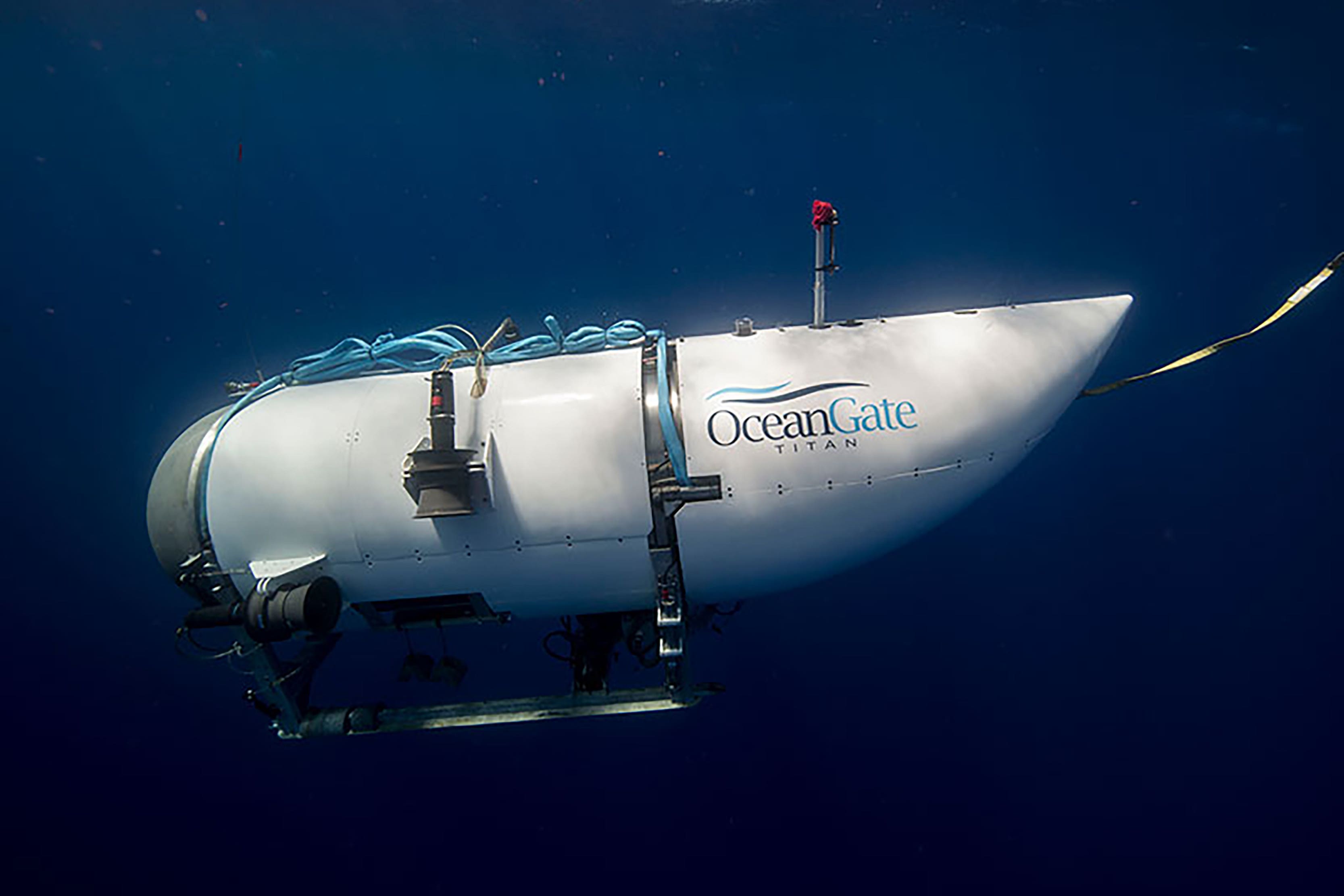

Rescue teams are still racing against time to find the missing 22ft submersible, named Titan, which was on a mission to dive near wreckage of the Titanic in the North Atlantic Ocean.

The vessel, with five people on board, lost communication with tour operators off the coast of Newfoundland, Canada, on Sunday.

Titan’s dive was one of many that have been made to the Titanic wreck, which is about 2.4 miles, or 3,900 metres below the surface, by OceanGate Expeditions since 2021.

Scientific research has helped us better understand the elaborate nature of the ocean, its environment and marine life, but there’s still a long way to go – and lot still isn’t known.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), more than 80% of the bottom of the sea is unmapped and unexplored.

How deep is the ocean?

The ocean floor is undulating. Covering 70% of Earth’s surface, the average depth of the ocean is 3,682 metres. The lower you go the higher the hydrostatic pressure (the force per unit area exerted by a liquid on an object).

The deepest point of the ocean – the Mariana Trench – is 11,034 metres deep. It’s located in the western part of the Pacific Ocean and is a 1,580-mile-long stretch (2,542 kilometres) of oceanic abyss.

According to a study published in the journal Earth-Science Reviews, there are at least four other deep parts of the ocean across the world, including the Molloy Hole in the Arctic Ocean, located at 5,669 metres below the surface. There’s also the Sunda Trench, also known as Java Trench, situated 7,290 metres underwater.

The deepest part of the Southern Ocean, which encircles Antarctica, can be found within the South Sandwich Trench, at a depth of 7,385 metres.

Lastly, a Puerto Rico trench site called Milwaukee Deep, the deepest part of the Atlantic Ocean, has a depth of 8,408 metres.

To put that into context, the deepest a scuba diver has ever gone is 332.35 metres (a record held by Ahmed Gabr for a dive in the Red Sea).

What is the ocean floor like?

Though the ocean floor can be dark, it doesn’t look the same across the entire ocean. So why is this the case?

“Natural geology,” said Sophie Benbow, director of marine at Fauna & Flora International, a conservation charity dedicated to protecting the planet’s threatened wildlife and habitats. “In the same way, we have mountains and river valleys on the land, they basically exist like that at the bottom of the sea. Affected by movements of tectonic plates (creates undersea volcanoes and hydrothermal vents) and oceanography processes, [for example] currents.”

This makes the seafloor potentially unstable and it can rapidly bury marine life or shipwrecks where you can also find strong currents.

What’s it like around 3,900 metres – where the Titanic wreck lies?

Many people imagine there to be a seabed with a vast amount of sand but like most of the deep sea, it’s a jagged and dynamic landscape made of sediments with as much variation as any place onshore.

Benbow described it as being “low [in] oxygen, near freezing temperature, a completely dark environment which provides unique habitats to species that have evolved over millennia to be able to thrive there… with unique features to survive in the very high-pressure environment”.

Dependent on the oceanic zone (the region of the open sea beyond the continental shelf is divided into four zones: the sunlight zone, twilight zone, midnight zone, and abyssal zone) a wide range of species can be found.

The depths of the ocean from 1,000-4,000 metres are called the bathypelagic or midnight zone.

Dr Huw Griffiths, a marine biologist at the British Antarctic Survey, said: “It’s called the midnight zone because [the] light in the ocean decreases with depth and below 1,000 metres there is no light from the surface, but some animals do produce light (bioluminescence) to attract prey and mates or to escape predators.”

What sealife can be found at this level?

The World Register of Deep-Sea Species (WoRDSS) has kept a comprehensive taxonomic database of known deep-sea and marine organisms since it launched in December 2012. So there is no doubt that the bottom of the ocean is teeming with a unique and special life.

“We would refer to the wonders of the deep rather than anything more sinister,” said Benbow. “I don’t believe there are species to be afraid of except perhaps in appearance as some of them are rather weird and wonderful.”

For instance, you would find one of the world’s deepest living fish, the Mariana snailfish, which over time has evolved to develop holes in its skull to keep its head from exploding due to the high pressures of the deep ocean.

There’s also the Dumbo octopus, named after the Disney elephant – the deepest living of all known octopuses. Due to its rarity, this creature has specially adapted so that it can more easily reproduce anytime it finds a mate.

There’s the Headless chicken fish, a type of deep-sea cucumber, also known as the Spanish dancer thanks to its unusual pink appearance.

Grittiths added: “On the seafloor, there are worms, brittle stars, starfish and other invertebrates. All of the animals at this depth are dependent on food sinking down from the surface layers of the ocean.”

At least 24 different species including fish, crabs and corals have been recorded from the wreck of the Titanic, he said.

“The ocean as a whole helps to regulate our global climate and is doing a great job of mitigating the ever-increasing impacts of fossil fuel emissions by absorbing and storing over 91% of the excess heat from global warming,” Benbow added. “It’s what makes marine sediments one of the most expansive and critical carbon reservoirs on the planet.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.