Join the bio bunch: Bertie Eden's vineyard is reaping the rewards of biodynamic wine-making

It's Old World all right, but Bertie Eden's vineyard operates along the distinctly new guidelines of biodynamics. And you can be a part of it...

The garden of Eden is a beautiful place. "There is great history here," says Robert "Bertie" Eden of his adopted home in the South of France, looking out over rolling hills bright with shades of green and yellow. In this wide landscape, framed by distant black mountains, only one village rises up from the fields on a mound, still medieval with its tightly clustered sandstone homes and single, square church tower. But the history is also in the fields. Look closer and they are filled with rows of what look like black, gnarled hands, twisting up from the soil. These are the vines.

"This is the oldest wine region in the world," says Eden, beaming. "They made wine for the Roman Empire."

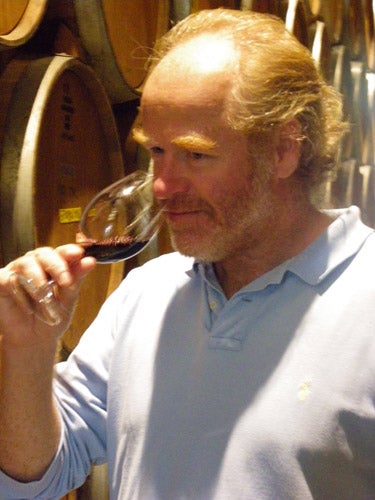

You would expect such reverence for tradition from an English toff, son of a Lord and great-nephew of Anthony Eden, the former prime minister; but the tanned, hearty Bertie Eden, his blonde hair swept back from a balding head, is also a rebel. His presence on this hillside testifies to that. He was destined for a life of politics and power, but chose instead to follow a passion for wine. Now he dares to make his own, in the ultra-conservative Languedoc of all places, in a way that is challenging his entire industry.

"Getting on the tractor, strapping on the mask and zipping up the overalls ready to spray the vines with chemicals made me think," he says of the moment he realised it was time to change. "It was like being a sewage pipe, spewing effluent into a river. I thought, 'This is revolting. We are going to drink this stuff. What are we doing?'"

So now Eden makes his wine according to biodynamics, a step beyond organics to a philosophy that sees the soil, the plants, ' the insects that feed on them, the animals that live there, the people that pick, press and ferment the grapes and the juice in the tank itself as part of a living system, influenced by the weather, the gravitational pull of the Moon, even the movements of the stars.

"When all these relationships are in balance," he says, "the soil is richer, the biodiversity in the vineyard thrives and the wine is better." Really? He quotes a blind-tasting by Fortune magazine, in which biodynamic wines were found to have "better expressions of terroir, the way in which a wine can represent its specific place of origin in its aroma, flavour and texture".

Then he thrusts a glass of wine into my hand. This is the moment I have been waiting for. The wines from the vineyards he keeps around the village of La Liviniere, under the name Château Maris, have won high acclaim. I'm not an expert – I think one respected judge may have knocked too much back before describing a glass of Eden's as offering "blueberry with brown spices, white pepper, bitter chocolate and chalk dust" – but I am about to be blown away.

Tasting wine made here, from grapes grown in these fields, is an extraordinary sensual experience (and one you can have for yourself, if you order from the Wine Club that Bertie Eden and the Independent on Sunday are forming together – see box below). He has opened two bottles, marked only with numbers, containing wine made in 2007 with Syrah grapes "from that vineyard over there, on the hillside". Inhaling over the deep bowl glass here in context is not like sniffing the bouquet at the dinner table at home: the scent is all-enveloping, almost as rich as the taste.

Richer, actually, because the wine itself is a little flat and disappointing. "Not ready," says Eden, shaking his head, "but it will be, in time." He pours from the other bottle and this time the scent is... awful. Eggs. "This is reduction," he says. "If we let it open up to the air, it will change." And it does, in the glass, mysteriously. The taste, though, is rich, elegant, voluptuous, seductive, all the words that are in my mind because Eden uses them to describe the sort of wine he is trying to make, but they're also true. It's wonderful. More, please.

I feel as if I'm being initiated into a secret religion, which is close to what Eden himself felt at the age of 12 when his father took "the big key" from the wall at their home in Dorset and led him down to the cellar one Sunday morning. John Eden, a Tory minister, was a serious wine collector. He was away a lot, and his son was at boarding school. Those moments were almost sacramental. "We would take the bottle upstairs into the dining-room, uncork it, sip it... and all that before going to church. Having a tipple in the morning with your father, when your younger brother is not part of it, is very special."

Eden was hooked. "For my Christmas presents, rather than roller skates or whatever, it was a book on wine or an envelope saying there were six bottles of Château so-and-so in my name at a dealer in London. Wine was the thing that belonged to me, within the family."

Beer was what got him thrown out of Stowe school, which he hated anyway. "I purchased exactly the same dustbins as were by the changing-rooms, hid mine in alcoves and brewed 100 litres inside them. I was very popular. Then I was caught."

Expelled, he persuaded his father to let him go travelling before joining the Army, but didn't come back. He flew to Australia, bought a motorbike, rode to the Barossa Valley and got a job in a vineyard, pruning. "That's how I learnt how to make wine, by watching and being shown."

Over the next two decades, Eden travelled from Australia to Italy then to France, Spain and California, nurturing the idea of a vineyard of his own. His friend, the New York banker Kevin Parker, helped him set up in 1997, but they soon realised the soil in the scattered vineyards they had bought had been exhausted by years of intense chemical farming. First, they went organic, then they realised that the cow manure they were importing as fertiliser, produced according to biodynamic principles, was extraordinarily good.

"I investigated, and discovered a total philosophy," says Eden, now 45. In practical terms, they use the manure; they plough the land with a horse; they treat the vines with "herbal teas" such as camomile instead of chemicals; and at harvest time they pick the grapes by hand. At night, after a full moon. The theory is that the gravitational pull is reduced, so less sap is lost with the harvest. Does it really, honestly, work?

"I don't know," says Eden, disarmingly. "But we have noticed that downward lunar cycles often coincide with periods of low pressure, meteorologically, so it is a good time. What is even more important, though, is the discipline: you are working within a calendar that acknowledges what is going on around you." In 20 years' time, the chemically farmed fields around them will be exhausted. "Ours will be in better condition that they were when we started."

Biodynamics is a rising force in the wine world, but Eden will lay down an even bigger challenge this year by building a state-of-the-art winery with no carbon footprint at all, producing more energy than it uses. Built on a hill outside the village, with hemp in the walls and floor and a living roof, it will maintain its own constant temperature with no need for air-conditioning, and the wine will be moved by gravity. Solar panels will provide power, and reed beds will recycle water.

This pioneering building, more ambitious than any in its industry, will not be open to the public; but members of the Wine Club will be able to have lunch there with Eden, and to taste the wines. That is, in the end, what it is all about. "Drinking copious quantities of biodynamic wine will make you feel a hell of a lot better than drinking copious quantities of industrially produced wine," he says, offering another glass. So that is what the two of us do next. You should try it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments