Pucker up, it's a bumper year for mistletoe

It may not be around for future generations, so we should enjoy the rites of this native plant while we can, writes Jonathan Brown

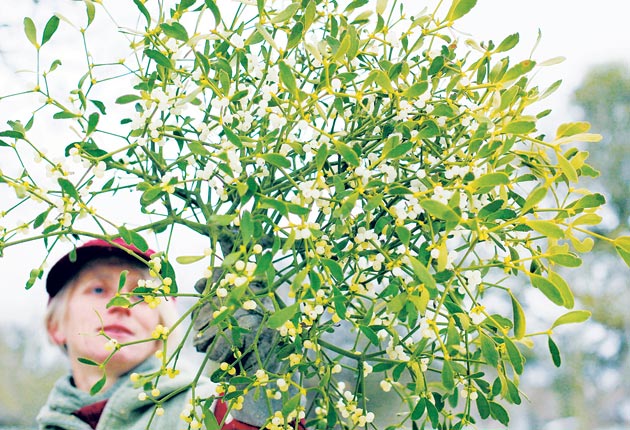

The frost was thick on the ground in Tenbury Wells this week and the breath of those who had gathered to bid for the bushels of mistletoe hung in the freezing air like a fog.

In many ways it was the perfect Christmas scene. For more than a century, bidders have been gathering in this picturesque Worcestershire market town, which lies deep in the heart of the three South Midlands counties famed not only for their cider but also for their mistletoe.

However, all is not comfort and joy for one of our most intriguing and evocative native plants. Although this year's harvest is bountiful and prices are buoyant, a long-term threat hangs over the future of homegrown mistletoe.

At the heart of the problem, explains Jonathan Briggs, a freelance environmental consultant and mistletoe expert, is the long-term demise of England's traditional apple orchards. Although the nation's drinkers might be turning in ever greater numbers to the delights of cider drunk over ice in a pint glass, the big companies that are reaping the rewards grow their apples in an entirely different, industrialised way from the traditional method. As a result, hundreds of ancient orchards which once supplied dozens of small cider makers and apple juicers are now lying derelict, their fruit left to rot on the ground while the mistletoe is allowed to run out of control.

In the short term, this is providing an abundance of berries and bright green foliage under which festive revellers can kiss. In the long term, it will lead to the destruction of the host tree and the loss of the invader on whom it is currently thriving.

"If you have traditional apple orchards, mistletoe will appear whether you like it or not. If you are prepared to tolerate it and use it as a winter crop, you don't need to encourage it. It is so prolific it will colonise on its own quite happily," said Mr Briggs. Apple trees are a favourite host and this part of Middle England is its favoured home, so widescale loss of orchards could have a serious long-term impact.

The National Trust, which this week launched a campaign to conserve indigenous mistletoe, estimates that traditional orchards have declined by 60 per cent since the 1950s, with up to 90 per cent lost in the former heartlands of Devon and Kent. However, the implications of the disappearance of an iconic crop that once thrived on small-scale, sustainably run farms are yet to be fully appreciated.

Another factor is the increased reliance on imports of mistletoe from Europe and northern France, though the decline of traditional apple orchards is also continuing apace in these areas.

Mistletoe became a Christmas fixture courtesy of the Victorians, and the fashion for decking the halls with it spread to northern and eastern parts of the country following the arrival of the railways.

Wherever it grows naturally, it has commanded more than its fair share of folklore. "The kissing tradition originated in the 19th century, but in the mists of time it has always been associated with the winter solstice and fertility," said Mr Briggs.

Very few other plants bear white berries, let alone deliver them from the boughs of a favourite fruit tree, which gives the white seed obvious parallels with human reproduction.

The seed of the mistletoe is spread by birds – traditionally the mistle thrush, but increasingly blackcaps which are over wintering in Britain in increasing numbers offering a potential ray of hope.

The name is thought to come from German words for dung and branch – a vivid reminder of how the seeds arrive on the host tree.

The plant is also important ecologically as it supports six specialist insect species such as the scarce mistletoe marble moth, and the appropriately named kiss-me-quick weevil.

This uniqueness made it an important fertility symbol for the Druids, with Greeks, Romans and many other cultures. The most celebrated myth can be found in Norse mythology, in which the god Baldur is killed by his brother with a sword made of mistletoe.

While the threat to the future of mistletoe mounts, the tradition is as popular as it has ever been. Supermarkets can sell sprigs at £2 each over Christmas, while florists have found it increasingly in demand for winter wedding bouquets and table decorations.

There is also mounting interest in mistletoe as a medicine. The use of the plant in the treatment of cancers is well established, while herbalists have used it to treat respiratory and circulatory conditions.

Reg Farmer, 81, has been harvesting mistletoe by hand since he was a boy. "I like it because I like orchards and I like being up a tree – although I have fallen down a few," he said. He recalls traditional winter dances where the plant was a commonplace accessory in his native Worcestershire.

"You would see the lads and girls with a bit of mistletoe. It was a real bit of fun and it used to bring people together. I think I've got a few kisses left in me yet," he added.

The second of the three traditional Christmas mistletoe sales at Tenbury Wells was held on Tuesday, and auctioneer Nick Champion had a busy day. Despite the freezing weather, he sold 950 lots during four hours of steady bidding for the 10kg bundles which fetch around £20 each.

Things have changed, he said. "We see a lot more buyers but they are buying less. We don't see the big fruit and vegetable wholesalers any more – they seem to have died out. The buyers are more specialist and we don't see the supermarkets. They don't like auctions because they can't control the price," he said.

Typical of the new generation of holly entrepreneurs is Alex Moss, 22, an Oxford chemistry student, and her friend and fellow student Jess Hills, 21. They were leaving the market at the close of bidding having bought five bundles, which they intend to sell outside the pubs and bars in Chelsea. They'll tie it up with ribbon and sell it from boxes around their necks like cinema usherettes.

They are anticipating earning more than enough to fund their Christmas celebrations. "This is the first time we have done it but it would be nice to think we might end up bringing people together. It really is quite romantic," said Ms Moss.

Myths and truths

*Mistletoe (Viscum album) can grow on a wide range of deciduous trees, including oak and apple. It is a hemi-parasite, deriving nutrition and water from the host tree, but photosynthesises through its evergreen leaves.

*Mistletoe is popularly supposed to be highly poisonous. It might cause sickness and diarrhoea, but it is not particularly toxic. A child who swallowed a couple of berries would probably not require any treatment. But if in doubt, call 999 or take them to your local Accident and Emergency department.

*The tradition of kissing under the mistletoe derives from the link with Frigga, the Norse goddess of love. Frigga's son, Baldur, had a premonition that he would be killed by his brother, Hodr, the blind god of winter. So Frigga asked every living thing to promise not to harm Baldur, but she overlooked the mistletoe. Loki, the Norse god of mischief, tricked Hodr into making a spear from mistletoe and killing Baldur. The world mourned and everything started to die. The gods resurrected Baldur and Frigga swore that mistletoe would never be able to hurt anyone again, but would become a symbol of love.

*Herbalists claim mistletoe helps lower blood pressure and has a sedative effect on the nervous system. It is used for arteriosclerosis and as a compress for varicose veins.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks