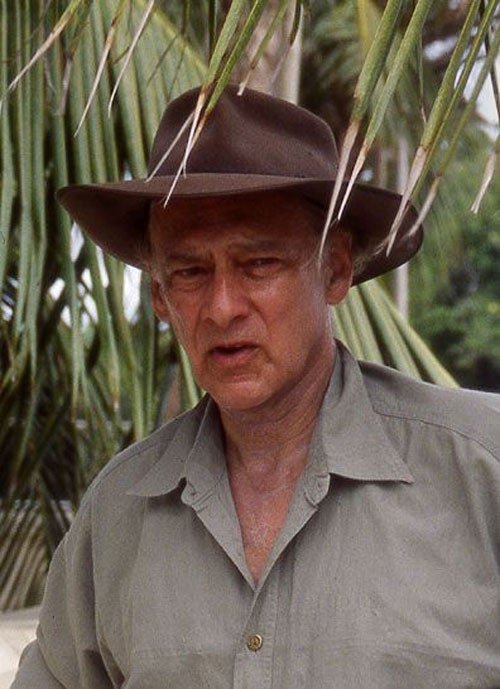

Sir Christopher Ondaatje: My soft spot for a big cat

Ondaatje's passion for leopards began when he was a boy. He tells Rebecca Armstrong about his love of the vicious, but vulnerable beasts

On retiring from the high-pressure world of finance, one might expect a millionaire businessman to settle into a gentle routine of golf, gardening and the odd gin and tonic. But when Sir Christopher Ondaatje turned his back on the boardroom he wasn't tempted by the quiet life. Instead, he longed for adventure and knew that the best way to find it was to track down the love of his life – leopards.

"Leopards are such unique creatures," he says. "They're paradoxical – sinister and ruthless, but at the same time charismatic and vulnerable." Ondaatje is almost as exotic as the creatures he loves. Born in Sri Lanka in 1933, he was educated in England before emigrating to Canada in 1956 with only a few pounds in his pocket. But his talent for business saw him set up the publishing house Pagurian Press, which eventually became the enormously successful Pagurian Corporation. However, while his wealth allowed him to make generous philanthropic gestures, donating $60m to a variety of causes in his 40-year career, his heart lay far away from the boardroom.

"The whole thing really started in 1946, when I was 12 years old, in what was then South-east Ceylon, but what is now Sri Lanka. I was with my father in the Yala game reserve and I saw my first leopard," he says. "Anybody who has seen a leopard will remember the first time – quite apart from its spectacular beauty, the leopard is a stealthy thing and it sorts of creeps into your line of vision and out again. It's a dangerous cat and it has a real aura of danger about it." In the two decades that have passed since Ondaatje sold his multimillion-dollar business, leopards have become a muse-like presence in his life and his work.

"I've written books about leopards and I've got a leopard in every single book I've written. In my first autobiography I used a leopard as a metaphor for my tyrannical father," says Ondaatje. "They're part of this world I've lived in since I chucked the gruesome world of finance." His latest book, The Glenthorne Cat, is an anthology of fictional and true stories which he was inspired to compile by his time on the trail of leopards. In it, Ondaatje recounts his own experiences of hunting for leopards alongside stories of man-eaters that terrorised villages across India and Africa, plus mythical accounts of the beautiful, if sometimes deadly, creatures.

"My love of and fascination with leopards has been tremendously rewarding," he says. "For me, tracking leopards is the most thrilling thing I can imagine. You work very hard to get to a situation where you can track one, I'll spend hours trying to see one but it doesn't matter. The prize is worth it." While Ondaatje has followed in the footsteps of some of the Empire's most famous explorers – "I think I am the only person alive today who has done all the Victorian explorers' journeys," he says – his prize isn't the leopard skins or mounted heads that were once such popular souvenirs. When Ondaatje shoots a leopard, it's with a 300mm camera and all he takes back with him are images of his prey.

"When I go out on safari, whether it's in Sri Lanka or Africa I take extraordinary risks to see a leopard. I will do anything to see one," he says. This obsessive approach has paid off for Ondaatje. "I'm one of the few people in the world to see a black leopard." Black or melanistic leopards are far rarer than their spotted relations as their dark hue occurs thanks to a recessive gene. They are difficult to see in the wild as they are usually found in the tropical rainforests of South-east Asia, where their dark hide camouflages them almost completely. On hearing that one had been spotted on the slopes of Mount Kenya, Ondaatje flew from the UK in a bid to glimpse one. "After getting up at 4am with three Masai guides, we surrounded a hill where the leopard had been seen as the sun came up. I looked up and there was the leopard 40 yards in front of us. It was extraordinary."

After taking a quick drink at a nearby stream the leopard disappeared, but Ondaatje was determined to see it again. "We came back later in the afternoon to see if it would come out looking for something to eat. I saw it in a tree with its tail hanging down. I sat there taking photographs for some time before it noticed us and jumped down. I was only 20 or 30 foot away. It was really stupid to be so close because if it had felt threatened it would just attack. But it is one of the most memorable encounters I've had."

Having tracked the big cats in Sri Lanka, India and Africa, he is under no illusion about the nature of the beast. "You have to be careful with leopards, you can never trust them. A cornered leopard is the most dangerous beast in the world. Having said that, it's also beautiful, but its beauty has caused it to be ruthlessly murdered for its hide. In Africa, in India, in Sri Lanka, they still poach leopards and they do still sell hides." As well as being hunted for their beautiful fur, which Ondaatje describes in loving detail as having "numerous rosettes on a creamy yellow which is spectacularly beautiful", leopards face an uncertain future as their natural habitats are threatened by humans. "Although an abundance of leopards has been slaughtered, they are not an endangered species. They're resilient. But as human territory expands, it is going to become more of a problem," explains Ondaatje. "We're moving into territories that really don't belong to us and even now, leopards maintain only a precarious foothold where they were once abundant. I would like people to be better educated about leopards."

According to the World Wide Fund for Nature, most wild-cat populations are declining and their habitats are shrinking. As more land is used for agriculture, prey becomes scarcer and cats, including leopards, are forced to kill domestic livestock, which causes farmers to guard their land and animals more carefully, creating an untenable situation for the future of leopards. Only by educating people and creating reserves and game parks can they be protected for the future.

So what does the future hold for Ondaatje now that the far-flung research trips that were required by his labour of love are over? A drink on the lawn or a spot of DIY? No way, says the unrepentant adventurer. "With my restless spirit and all the devils that are in me, every now and again I have to go and do this crazy jungle stuff."

The Glenthorne Cat and Other Amazing Leopard Stories £7.95 is published by HarperCollins

Lore of the jungle

* Leopards are found across sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia

* The origin of the modern leopard is estimated to have begun 470,000 to 825,000 years ago in Africa, followed by a more recent migration into and across Asia 170,000 to 300,000 years ago

* Leopards are smaller than lions, and can tear their prey apart with their hind legs while their sharp jaws lock into the throat of their prey to strangle it

* The animal's favourite foods include a wide range of birds and mammals, among them guinea fowl, warthogs, hares and, particularly, smaller antelope such as impala and gazelles

* A large leopard can weigh as much as 200lb, but the average weight for the animal is 110lb. They stand about 30 inches high at the shoulder and the full length of a leopard, including its tail, can reach up to nine feet

* Leopards are territorial animals and their range varies very much according to food supply. A leopard's territory can be as little as half a square mile and as much as four square miles

* Leopards mark their area by calling with their hoarse, saw-like cough or by spraying their urine on trees, branches, bushes, ant hills, rocks and any other prominent landscape feature. With their sharp claws they also mark trees, rocks and places on the ground

* The leopard's voice is barely audible. Its rasping cough is used not only as a territorial claim but also as a form of greeting or contact. Alarm or anger transforms the cough into a deeper growl that becomes a screaming roar. A leopard's contented purr is sometimes more audible than its cough

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments