The Big Question: Are electric cars the answer to Britain's environmental problems?

Why are we asking this now?

Because Gordon Brown is promising, as part of his forthcoming Budget, steps towards the mass introduction of electric cars on to Britain's roads. This would be part of a "green recovery" from the recession, which could help make Britain a world leader in manufacture and export of electric, and hybrid electric/petrol driven vehicles.

Why does Mr Brown want to do that?

Not only because it might well be a terrific business opportunity, but even more, because tailpipe emissions of carbon dioxide from motor vehicles are a major contributor to the greenhouse gases responsible for global warming. Road transport emits about 25 per cent of Britain's total CO2, with passenger cars alone accounting for nearly half that figure – and car use is continually growing, all over the world. Britain alone now has a fleet of 27 million cars.

So is this revolutionary thought on Mr Brown's part?

Well, to make a major move on it would be something of a political coup, but the idea is not new at all. It is recognised globally that the internal combustion engine is a very big part of the climate change problem, and that transport will have to be "decarbonised" as part of the worldwide move to cut greenhouse gas emissions. Britain in particular has agreed to cut its CO2 by a huge 80 per cent by 2050, and in December, the Government's new Climate Change Committee recommended in its first report that there should be an initial 42 per cent cut by 2020 (the Government still has to accept this). The committee chairman, Lord Turner of Ecchinswell (who as Adair Turner was director-general of the Confederation of British Industry) said that if this goal was to be realised, in no more than 12 years from now, 40 per cent of all the vehicles on Britain's roads would have to be electric powered (or hybrid).

Is that a very practical idea?

The Government seems to think so. In 2007, when Mr Brown was Chancellor, he asked Professor Julia King, Vice-Chancellor of Aston University, to carry out a special review of low carbon cars, and the King report, published with the Budget last year, offered 40 recommendations for reducing vehicle emissions. Professor King said: "There is huge potential for CO2 savings, with a role for vehicle manufacturers, fuel companies, consumers and Government."

Low-carbon cars are running already, are they not?

Yes, indeed they are, mainly using electric battery power. For the most part they don't go nearly as fast or as far as petrol vehicles, but the major manufacturers are now coming to grips with that, and over the next few years we will see hybrid, electric and possibly hydrogen-powered cars coming in that will rival their petrol-driven equivalents in performance. And of course, they produce much lower CO2 emissions (the hybrids) or zero CO2 emissions (the battery and hydrogen cars), and are already very popular with many municipalities.

So Mr Brown's scheme is a win-win? We'll be well on the way to solving our environmental problem?

Ah. Well. Perhaps not: we are going to need a great deal of extra electricity if Britain is going to adopt these plans. So they will need to be thought through fully. It's all very well if you're driving an electric car here, and a hydrogen car there. But some obvious questions emerge if everyone gets involved: what happens if you want to convert all 27 million of the vehicles on Britain's roads to battery power? Where do you find the electricity to charge those batteries? Remember, electric cars do not have a very long range on one charge – enough for tootling about the city during the day – but basically they have to be recharged every night. If you add 27 million hefty car batteries being recharged nightly to Britain's current electricity load, what will that involve?

Well, what will that involve?

Professor Julia King thought it would add about 16 per cent to Britain's electricity demand. That's quite a lot of extra electricity to find, but we can probably find it. However, the pressure group the Campaign for Better Transport points out that the 16 per cent figure refers to the charging of all 27 million cars being averaged out over the course of a 24-hour electricity production period, when in reality it's not like that. Virtually all the cars would be charged just in the six-hour period from midnight to 6am – and remember, the National Grid cannot store electricity, we can only use what is being produced at a given moment.

So what are the implications of all this?

Analysis the Campaign for Better Transport commissioned from Keith Buchan of the Metropolitan Transport Research Unit suggested this would trigger an increase in UK electricity demand that was absolutely enormous. Mr Buchan calculated that the UK's 27m cars, using 50 kilowatt hours each per day, would need about 1,350 gigawatt hours. He reported: "Over 24 hours, the existing capacity could almost cope with this demand, but nothing else. In fact, most studies suggest off-peak charging (midnight to 6 am). This immediately has the effect of inflating the impact of car charging fourfold. The six-hour capacity of the system is 330 gigawatt hours, less than a quarter of what is required." So to accommodate Gordon Brown's all-electric car vision, Britain's electricity capacity would have to quadruple.

Where would all this electricity come from?

That's the point. If you think all that new electricity can be produced from renewable energy, from wind power and solar arrays, fine. But in reality, to get such an enormous new amount, you would probably have to build more coal-fired power stations and produce enormous new amounts of CO2. The Campaign For Better Transport's Richard George points out: "You're not solving the CO2 problem at all. You're just shifting it somewhere else."

So green, electrically-powered cars are not really greener?

Well, anything that really does reduce CO2 emissions – like 20 people taking one bus instead of 20 people each driving an individual car – is worth doing. But the attractions of green cars may not be quite what they seem. Richard George says that if you drive an average amount in an average car, it is probably not even worth changing to a lower-emissions vehicle, because the amount of CO2 that will have been produced in making the new car will exceed the emissions that you will save.

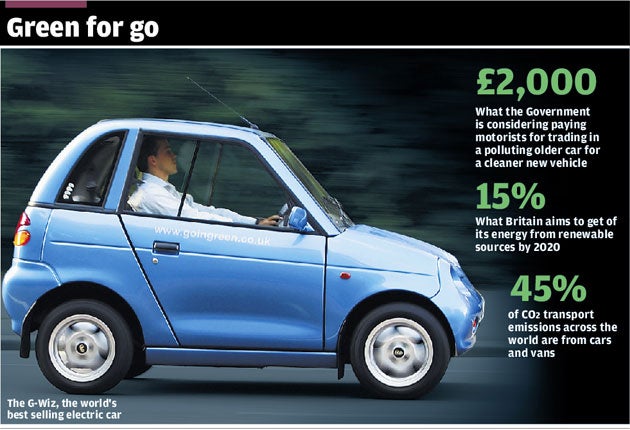

What about the scheme to scrap your car and buy a greener new one?

The Government is thought to be considering this – paying people to scrap their old bangers and buy better vehicles – and according to Richard George, this will do more for the car industry than for the environment, because the new cars you can buy to qualify will not necessarily be very environmentally-friendly. His own solution is a public transport boost. "There is a such a thing as greener transport," he says, "but there isn't really greener motoring."

Will Gordon Brown's plans for green motoring really be greener?

Yes...

*Greenhouse gas emissions from motor vehicles are one of the major contributors to climate change

*Anything that cuts down tailpipe emissions of greenhouse gases is to be welcomed

*Electric and hydrogen powered vehicles produce no tailpipe CO2 whatsoever

No...

*The electricity you need to power big fleets of electric cars may itself involve enormous emissions of CO2

*Hydrogen-powered cars will need lots of electricity to make hydrogen, which may involve big CO2 emissions

*Co2 savings in a lower emissions vehicle may be exceeded by the carbon expended in making it

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks