The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

How close are we to a cure for multiple sclerosis?

After watching her mother struggle post-diagnosis, Jessie Williams investigates the breakthroughs and dead ends that could improve our understanding of the ‘invisible’ disease... and one day halt it altogether

My mum has always been a very active woman. A natural long-distance runner, she would run through Hyde Park when she lived in London during her twenties, relishing the feel-good kick the endorphins gave her. As she got older she competed in numerous running events raising money for Cancer Research. One of my clearest childhood memories is watching her – arms outstretched, sweaty face beaming – cross the finish line at one of the many Race for Lifes she ran. She would always beat her friends; as much as they tried they could never catch her. I remember hoping that one day I would be able to run like her.

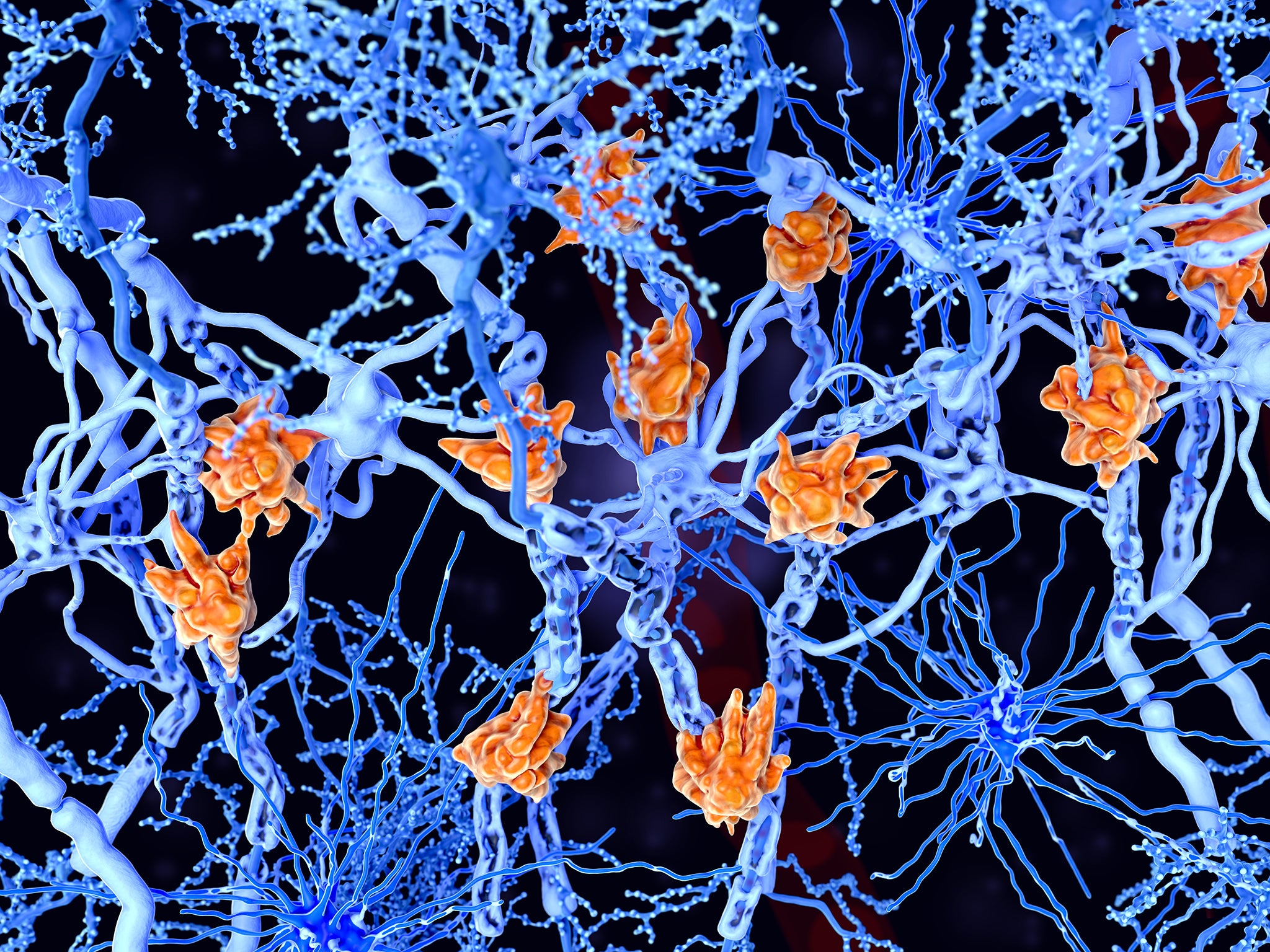

In 2006 she suddenly stopped running. I wasn’t sure why; she was a healthy, fit woman in her early forties. I found out later that it was because she had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. MS occurs when your immune system mistakenly attacks the protective coating around nerve fibres (called the myelin sheath), which is the biological equivalent to plastic insulation around electrical wiring. This is a vital part of how our bodies function, as the nerve fibres act as pathways delivering messages from the brain to the rest of the body. In people with MS, these messages slow down or get lost – imagine an internal traffic jam caused by a collapsed bridge. There is a glitch, a spasm, a tingling feeling spiralling through limbs, a loss of sensation. Like a Trojan horse, silently attacking from the inside. Symptoms vary but include anything from blurred vision, fatigue, numbness, balance problems and, in severe cases, paralysis.

It was when my mum began struggling to run that she realised something was wrong. “I thought I had a problem with my back because I kept dragging my right leg when I got tired,” she says. However, an MRI scan revealed she had relapsing-remitting MS, the most common form of the disease where you experience attacks when your symptoms flare up (known as a relapse), followed by a period of recovery. The diagnosis was “devastating” she tells me. We’re sat on my bed, trying to keep warm on a particularly chilly day in late December, and it’s clear that even thinking back to the moment is painful. “I did try to run [after the diagnosis] and I nearly fell into the road because I tripped over a curb, so I thought it’s just not worth it, I’m going to break something or do damage.” She says she misses running: “That feeling you get when you’ve done a run – the sense of achievement. I miss that.”

It is estimated that MS affects over 100,000 people in the UK, with 5,000 new diagnoses each year, many in people in their twenties and thirties. According to the NHS, it is the most common disabling neurological disease of young adults in the UK, and women are roughly twice as likely to have it than men. Ask anyone and they will probably say they know someone with MS – perhaps it’s an aunt, a granddad, a mother. Despite this, it is shrouded in mystery. The exact causes are unknown (it is believed that environmental factors and genetics play a part), symptoms are unpredictable and there is no cure. Yet.

Last year, an exciting discovery was made by scientists at the MS Society Cambridge Centre for Myelin Repair (CCMR), which could have the potential to prevent MS developing to the progressive stage, when symptoms grow worse and there is no recovery period. Set up in 2005, the centre is based in one of the many colossal glass buildings in the rabbit warren that is the Cambridge Biomedical Campus. A place where some of the greatest minds in the country converge, and, as I found out, a place where it is very easy to get lost.

I visit on an overcast Monday in January: outside slate-coloured skies threaten rain, while inside state-of-the-art equipment gleams behind glass. Professor Robin Franklin, director of the CCMR, sips on his coffee as he explains his research. In his office, alongside awards and an illustration of the human brain (“By far the most interesting organ in the body by some considerable distance; the liver didn’t write Shakespeare’s sonnets”) hangs a microscopic photograph of a rat’s central nervous system repairing itself. It is this cluster of grey blobs that Professor Franklin and his team have been studying, and which has led to this breakthrough.

To understand the discovery, Professor Franklin explains, you must know what an oligodendrocyte is. “These are very abundant cells and they make myelin sheaths around the brain and spinal cord – collectively called the central nervous system. In MS, for reasons that are still pretty unclear, the immune system gets confused and starts to destroy the oligodendrocytes, and especially the myelin sheath.” When the myelin sheath comes off the nerve fibre, two things happen: “The nerve fibre can’t conduct impulses as efficiently, so the whole thing slows up, and secondly (and long term more seriously) because the myelin sheath protects the nerve fibre, it is very vulnerable without it and so the nerve fibre itself may degenerate,” he says, adding: “If this happens they are gone forever.” It is this degeneration that underpins the later progressive phases of the disease.

How to ease MS symptoms

Stress can trigger relapses in people with MS, so your emotional wellbeing and mental strength is vitally important.

Try to avoid situations that cause a lot of stress on the mind and body – that could be extreme temperature change, or it could be pressure at work, and make your surroundings as calm and stable as possible.

“Early on in adulthood your stem cells are very efficient at regenerating new oligodendrocytes, which is why in the early stages of the disease it has a relapsing-remitting phase, so you have episodes where the immune system flares up and destroys the oligodendrocytes and myelin sheaths and then it all settles down and your stem cells regenerate the damage,” says Professor Franklin. However, as you get older, your stem cells become less efficient. “So, by the time you reach middle age the stem cells have become so ineffectual, they’re not able to make myelin sheaths sufficiently quickly to stop the nerves from degenerating.” In other words, the longer a nerve fibre is exposed, the more damage occurs.

The crux of the issue is: how do you get stem cells to create oligodendrocytes in old age? This is where metformin comes in. Professor Franklin and his research team found that metformin, a drug widely used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, can rejuvenate ageing stem cells so that they then become oligodendrocytes much more efficiently, as if they were young brain stem cells. He explains: “What we did was we took aged rodents, we induced a little area where they lost their myelin and gave metformin, and it accelerated the speed of healing – so much so that it was indistinguishable from a young animal.”

It was a major triumph, says Professor Franklin, who is clearly very excited. “It really got to the heart of why stem cells change with ageing and also what you can do about that, so those age-associated changes are not immutable; they’re not cast in stone.” Clinical trials using metformin as a regenerative medicine for people with MS are planned to start this year. “What’s particularly good about metformin is that it is a well-understood drug, which means it won’t have to go through the long and expensive process of drug development,” he says. Despite this, it could still take over five years for metformin to be used as a treatment, according to Dr Alasdair Coles, a consultant neurologist at Addenbrooke’s Hospital and professor at Cambridge who oversees trials of experimental treatments with MS. “A phase two trial will take two years to complete and a phase three trial will take a further three. So, with no delays to funding or on behalf of regulators, I would estimate seven years,” he says.

Dr Susan Kohlhaas, director of research at the MS Society, believes a lot of progress has been made in managing the disease over the past two decades. “If you think about where we were 25 years ago, there were no disease-modifying treatments for anybody with MS. Today, we have 14 treatments available on the NHS for people with relapsing forms of MS. We have one treatment available for people with early stage primary-progressive MS, and one that is hopefully on the way for people with early stage secondary-progressive MS.” In the first half of this year, the MS Society will be launching a clinical trials platform for testing new treatments, which is the single biggest investment the charity has ever made. “It’s a major programme of work for us and we’re hoping it will give us a structure and a platform in which to test treatments rapidly and get them to people with MS as quickly as possible,” says Dr Kohlhaas.

Regular gentle exercise

Staying active – even just a daily walk, or yoga – can help combat fatigue, and build muscle strength.

Wendy Hendrie, a specialist MS physiotherapist, says: “When people start to have problems with their legs or balance, their brain will automatically ‘cheat’ by finding quicker ways of doing things. For example, if your legs are a bit weak, without realising it you will begin to push up from a chair using your arms. You may favour your stronger leg as you stand up.”

This will inevitably make your core weaker and your weaker leg even weaker as you’re using them less. Wendy says to try to avoid this. “When you point this out to people and ask them to stop using their arms, their core and therefore balance improves.”

Will there ever be a cure for MS? Many people I spoke to were hesitant about using the C-word. The lack of understanding of the causes of the disease makes finding a cure difficult. “No autoimmune disease in humans has been cured,” says Dr Coles, but he adds that “we will be able to control the disease so it does not cause permanent disability in most people”. Dr Kohlhaas agrees: “What I will say is that we can see a future where nobody has to worry about their MS getting worse.” There are already drugs available which tackle the inflammation causing the damage, known as immunoregulatory drugs. Professor Franklin compares these to firefighters dousing the flames of a burning house. But you then have to rebuild the house, which is the second phase of treating the disease – this is the tricky part. “The analogy I’ve used in the past ns one [part of the treatment] is Fireman Sam, the other is Bob the Builder,” he says. It is the combination of both which will be crucial in halting MS.

Rebecca Naylor is sceptical about talk of a cure. “Several times a year, if not several times a month, somebody has discovered a cure for MS, and it’s been that way for 23 years. So talk to me when it turns into something tangible.” Naylor grew up in what she calls an “MS Family”. Her dad had the disease, as does her uncle, and in 1985 at the tender age of 17, she was diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS. “It was shocking for me, but it was not unfamiliar,” she says over FaceTime from Ontario, Canada. The symptoms that led to her diagnosis were extremely slurred speech (“I was just unintelligible for about two weeks”) and blurred vision, then later the same year she had a full paralysis on the right side of her body. “The full paralysis was only for a few hours but then it took several months to regain full movement.” Ever since she has struggled with balance, coordination and fatigue.

Naylor hasn’t taken any drugs for her MS since 2007, and her last relapse was in 1998. Keeping her stress levels down, going to the gym and staying healthy are what helps her manage the symptoms, but most importantly she believes a positive attitude is essential. It’s obvious from the way she talks about her MS that she’s a fighter. “Sad as it is for me to say, part of the reason that I developed the attitude and determination that I have, is that I watched my dad take the opposite route. I loved my dad dearly, but at the same time I watched him not fight very hard to stay well.” She says she sees a correlation between people who expect themselves to deteriorate and the people who do. “I think you can become a diagnosis through your thoughts. If you think about it and fear it so much, you actually manifest it as your reality.”

Address infections immediately

Infections such as a UTI, or even a cold, often bring on relapses, so make sure to treat them as soon as you are aware you have one.

Wendy Hendrie, a specialist MS physiotherapist, says that the advice she gives her patients is not to give up. “Keep going and keep as positive as you can,” she says, but admits that this is difficult when you have an unpredictable, progressive condition. Another piece of advice she gives is to stay as active as possible: “We know that exercise may have a neuroprotective role in MS.” She says that this was apparent in the results of a trial published in The Lancet in 2019 which showed that regular standing in a frame helped improve the strength of people with severe MS who spend a lot of their day sitting down. “This paper showed that people can develop insidious secondary complications of inactivity which can mimic disease progression but which are actually due to inactivity.” Hendrie compares regular exercise to cleaning your teeth. “You should do it every day not to necessarily get stronger (your teeth don’t keep getting whiter!) but to keep things as good as possible for as long as possible.”

But, for many with MS even putting one foot in front of the other can be a struggle. So how do you find the strength and balance needed for regular exercise? The answer may come as a surprise: socks. There’s a YouTube video of Naylor doing leg lunges (something she finds difficult to do, particularly on her right side) wearing a pair of special socks developed by Voxx, a neurotechnology company that produces insoles, patches, and socks with an inbuilt tactile simulation pattern. When the pattern touches your skin it triggers a response in the nervous system. Naylor does her leg lunges with and without the socks, and it is clear she finds it much easier to do them while wearing the socks. She rises slowly and smoothly out of the lunge with only a slight wobble on her right side – without the socks she can’t even lift herself out of the lunge. In the video her excitement is palpable, and it hasn’t dimmed two and a half years later.

Intermittent fasting

A study by scientists at Washington University School of Medicine found that mice that were fed every other day had a change in the balance of immune cells and hormones in a way likely to reduce inflammation.

Previous studies have shown that fasting-mimicking diets have reduced the number of immune cells attacking myelin, and may also help to promote myelin repair. However, similar studies done on humans haven’t been as conclusive, and the effectiveness of this type of diet for people with MS is still relatively unknown.

Talk to your MS specialist before making any major dietary changes.

She discovered Voxx at a wellness conference in 2017. “I passed this booth where this guy was doing this balance demo with socks and I was like, what is this guy doing?” He explained that he was fixing people’s balance with socks. “I just laughed – like, are you kidding me? I was paralysed 20 years ago and I have major balance issues, there’s no way that putting on this pair of socks is going to fix my balance.” Long story short, she was blown away and now wears the socks 24/7. She has also joined the Voxx team as a speaker, spreading the message of how the technology has improved not only her balance, but also her flexibility, and even helped with pain management. “Now when I do the lunge with and without [the socks], there’s still a difference but it’s not nearly as dramatic as it used to be, because I am just so much stronger, which is really cool.”

For Alister Bailey, a former British Superbike racer, cryotherapy – an extreme-cold treatment – helps him deal with the symptoms of his secondary-progressive MS. “My life has genuinely changed,” he says. Bailey puts this down to whole-body exposure to temperatures of -135C in a chamber filled with liquid-nitrogen for three and a half minute sessions – a therapy usually used by professional athletes to improve performance and aid recovery. “I can lift my mood and improve mobility by having a short session of treatment. I try to use the chamber every day and anticipate my afternoon fatigue by having the treatment around mid-morning,” he says. After being left bedridden, temporarily blind, and unable to move when his MS first developed 10 years ago, he says he has now gained control of his condition for the first time.

First developed in Japan, the treatment arrived on our shores in the 1980s, and is now frequently used to treat conditions such as arthritis, rheumatism and fibromyalgia, as well as MS. Research into the benefits of cryotherapy has produced contradictory results, but some believe it tricks the body into “fight or flight” mode, which boosts circulation and produces adrenaline which gives energy to muscles and reduces inflammation. Bailey says he is often ache and pain-free following the treatment at his local CryoAction lab in Poole, Dorset, and now works for a construction company.

Last summer my mum suffered a relapse. It was her first one in years, and was most likely triggered by the stress of work and moving house. She says it was a particularly bad one. “It started with tingling up and down my legs and then I just realised how desperately tired I was – normal everyday activities exhausted me and all I wanted to do was sit down.” It took six weeks for her to properly recover, and in that time she barely left the house. For someone who loves being outdoors, it was incredibly frustrating. “You want to keep moving but you just can’t and you get a bit desperate thinking ‘when is it going to pass, when can I go and do things?’ But then it does pass.” She says that when a relapse hits she struggles lifting her right foot and worries about going out on her own – even navigating stairs can fill her with dread.

The difficult part for me is the fact that I don’t look like I have MS. I’m 40, I’m tall, I’m thin, I’m blonde. I’m just your average person walking down the street, I don’t use a walker, I don’t look crippled

The hardest part of the disease, she tells me, is the invisibility of it. “People don’t really know about it, so they might think you’re a little bit odd, they might think you’re drunk when you’re walking. You can’t really just tell people, and sometimes you can’t function properly, so people don’t understand. They don’t realise something’s wrong, they think you’re just a bit strange,” she says.

Naylor says something similar. “The difficult part for me is the fact that I don’t look like I have MS. I’m 40, I’m tall, I’m thin, I’m blonde. I’m just your average person walking down the street, I don’t use a walker, I don’t look crippled.” But the disease has had a significant impact on her work. She used to be a full-time teacher, but because of her symptoms she’s had to scale it back to just supply teaching. “A lot of the things people can’t see. They can’t see your fatigue. When you say you’re fatigued people don’t understand that’s not the same as tired.” Naylor describes having to constantly direct her muscles. “It’s like the left side of my body is on autopilot and the right side is on manual.”

There is an overwhelming lack of awareness around the diversity of MS symptoms, which is largely down to the media image of a person with MS being someone in a wheelchair. This is starting to change. Last year at the Vanity Fair Oscar’s afterparty, the actress Selma Blair defiantly walked the red carpet with a cane, wearing a chiffon cape which billowed behind her like a superhero. She was diagnosed with MS in August 2018, and uses her Instagram to share the reality behind the disease.

Healthy eating

It goes without saying that a healthy diet is good for improving your quality of life, but in particular consuming plenty of omega 3 and fish oils is beneficial for people with MS.

Studies have found that they can reduce the relapse rate, so stock up on salmon, mackerel, herring and sardines.

Another well-known person who has MS is American writer Joan Didion. She captures the unpredictability of the disease in The White Album when she describes her confusion after her diagnosis in the 1960s: “I might or might not experience symptoms of neural damage all my life. These symptoms, which might or might not appear, might or might not involve my eyes. They might or might not involve my arms or legs, they might or might not be disabling.” Didion writes that her neurologist advises her to “lead a simple life… not that it makes any difference we know about.”

Although we’ve made significant strides in understanding the disease since then, it is a conversation my mum recognises from her own visits to specialist MS nurses, which she admits she finds “pointless” due to the lack of answers they can give her. “You go through all these tests and they don’t tell you anything. And then I ask [the MS nurses], ‘do you think I’m worse? Do you think I’m better? What do you think is going to happen next?’ And they say, ‘we can’t tell you, everyone is different. We just have to see.’” Furthermore, in the summer when she experienced the bad relapse, the local MS nurses didn’t respond to her phone calls, despite her leaving numerous messages saying she was struggling and needed advice.

The uncertainty created by the disease is often exacerbated by the underfunding of specialist MS services. According to the MS Trust, right now around 68,000 people with MS live in areas where there are not enough MS nurses to look after everyone. Hendrie says there’s not just a lack of MS nurses, there is also a lack of MS specialist neurologists and therapists. “Unfortunately, the trend is for specialist posts to be cut back. There are far too many managers in the NHS and not enough clinical staff,” she says. Dr Coles agrees: “The NHS is particularly poorly funded in areas of chronic neurological disability. We need more people with expertise in neurorehabilitation, neuropsychology and in mental health conditions associated with MS.”

I ask my mum if she ever worries about the future and her symptoms worsening. “I don’t really think about it, because I don’t really like to admit that it’s happening,” she replies, before getting up and saying she really ought to start making dinner. Her running days may be over, but she never stops moving – there is always something to do. She still walks to work every day, she still ambles in the countryside where she lives, she still dances in the kitchen to her favourite songs; she refuses to let MS define her.

In May I will be running a half marathon for the MS Society. On a crisp evening in early January, I start my training. I run around my local park as the sun sets; golden beams filter through the trees. My feet pound the pavement, propelling me forward, faster and faster. I inhale a lungful of air, my thighs burn, but my legs don’t stop. I’m pleasantly surprised – this is my first run in six months. I feel like I could go on forever. I pass the playground, and the maple trees with the naked twisting branches, the lake, and the rows of terraced houses, on and on, until I reach the edge of the park. Even when Rihanna’s dulcet tones stop pumping through my headphones, and my chest feels like it’s going to burst, I keep going. At the back of my mind is the memory of my mum crossing the finish line. I’m running for her.

To sponsor me, please click here.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments