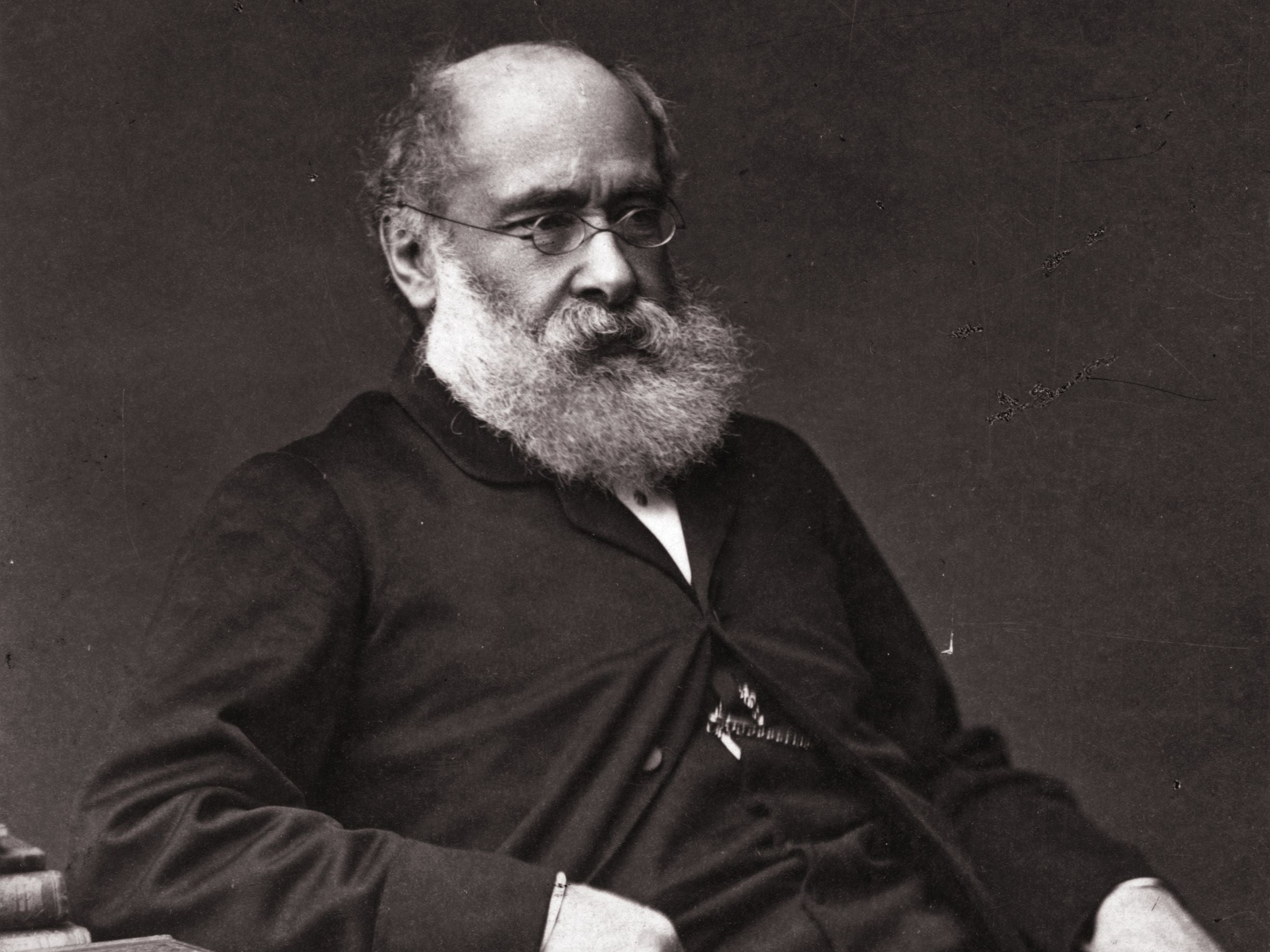

The Way We Live Now by Anthony Trollope

From The independent archive: Amanda Craig on ‘The Way We Live Now’ by Anthony Trollope

By rights, I ought to loathe The Way We Live Now. It starts with a withering portrait of a woman author writing begging letters to three different literary editors about her new novel. It’s unremittingly racist about Jews and respectful to posh people. Yet I adore Trollope, and re-read him regularly. I owe to him, more than any author, my moral education, my understanding of how British society still works, and my determination to write novels that are, as far as I can make them, also about the way we, too, live now.

Trollope’s genius came upon me not as a thunderclap but as a slowly evolving, wholly delightful friendship. By the time I read TWWLN, I was half-way through his Palliser novels with their incomparable portrait of political life, and had been enchanted by The Eustace Diamonds. TWWLN, his great dark novel, begins as pure satire on literary life (Lady Carbury wants to write not good books, but ones that are said to be so), on the kind of credit-based greed that is especially evident in our own time, and on the perpetual struggle between what is honest, loving and kind in people and what is venal. Trollope writes with brutal frankness about the three subjects that remain hot potatoes in our society: money, class and race. Merely by portraying these to his Victorian audience, he is much more radical than many suppose. Even as a satirist, he can’t help adding depth.

Lady Carbury is despicable, yet a loyal wife and loving mother of the stone-hearted Felix. The foreign financier, Melmotte, is despised even by the author, let alone the “curs” who fawn on him – yet he achieves a kind of nobility, and is, ironically, found to leave a genuine fortune after his death. Henry James sneered at Trollope for having “a complete appreciation of the usual”, but we recognise Melmotte as both unusual and real in the way that none of James’ characters were – in being a prescient portrait of the real-life swindlers Maxwell and Madoff.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies