The true cost of 'fast fashion': why #whomademyclothes is trending this week

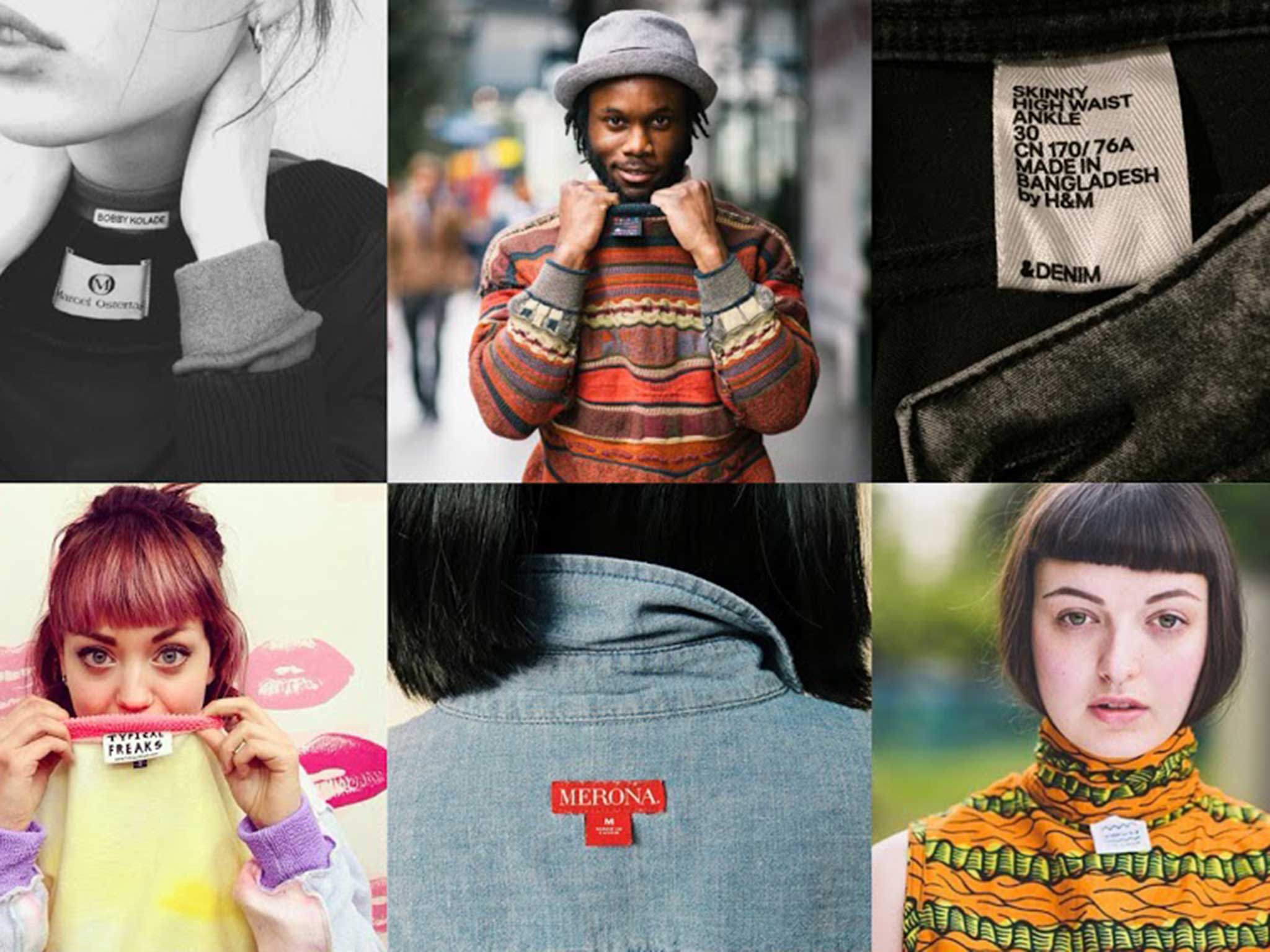

The style industry’s ethics are under scrutiny this week. As we near the third anniversary of the collapse of the clothing factory in Bangladesh that killed over 1,000 people the public asks #whomademyclothes...

Fashion and politics do not make the happiest of bedfellows. For all its virtue signalling, a system based on inequality and insecurity – that’s the fashion business – has little room for genuine compassion. However, this week the beneficiaries of sweated labour are being asked to examine their consciences – and their order books – as part of Fashion Revolution Week.

This is a global response to the collapse of the Rana Plaza factory complex in Bangladesh that killed 1,134 people and injured 2,500 more, on 24 April 2013. And as well as a “label selfie” campaign on social media, it has already provoked a special Fashion Question Time in the House of Commons, hosted by Labour MP Mary Creagh, at which the industry was urged to come clean about its foreign suppliers and help to clean up the iniquitous conditions under which their workers are hired.

FASHION IN NUMBERS

£2 trillion annual turnover of the fashion industry

£100m value of used clothing that goes to landfill in the UK each year

£2 average daily wage of a garment worker

25p amount that, if added to every item of clothing, would cover the costs of a living wage for all workers, and for factories to meet safety standards.

170 million estimated number of child labourers around the world, many for textiles industries

The disaster graphically demonstrated the true cost of quickly changing trends, or “fast fashion”, for high-street brands such as Gap and Benetton: dangerous working conditions, long hours and little pay for the garment workers. And what made it worse is that 2013 was global fashion’s most profitable year to date.

“Most of the public is still not aware that human and environmental abuses are endemic across the fashion and textiles industry and that what they’re wearing could have been made in an exploitative way,” says Carry Somers, the co-founder of Fashion Revolution, who argues that transparency is the first step towards persuading brands to take responsibility for working conditions across the supply chain. Which is why, this week, people are taking those “label selfies”, tagging the brands of what they’re wearing, and asking #whomademyclothes.

FIVE ETHICAL FASHION BRANDS

People Tree

People Tree is at the forefront of ethical fashion. Garments are handcrafted using traditional skills that support rural communities. peopletree.co.uk

Gather & See

A collection of small-scale hand-made brands that pride themselves on their aesthetics as well as their ethics. gatherandsee.com

Luva Huva

If you’re looking for sexy and sustainable lingerie, then Luva Huva is the brand for you. All items are handmade in the UK. luvahuva.co.uk

Beyond Skin

Natalie Portman, Anne Hathaway and Leona Lewis are a few of the high-profile celebs who wear these stylish, vegan, shoes. beyondskin.co.uk

Matt & Nat

“Live beautifully” is the motto of this stylish vegan bag brand whose linings are made from 100 per cent recycled plastic bottles. mattandnat.com

Often the answer will be “poor Bangladeshis”. But similar working conditions prevail across the globe, from South America to China – and the big brands seem blithely unconcerned. The international Behind the Barcode report, published last year by the charity Baptist World Aid Australia, found that 86 per cent of brands surveyed made no attempt to ensure a living wage across their supply chains, and half didn’t even know the locations of the factories in which their garments are made. And while H&M and Inditex (Zara) have taken action to pay wages above the legal minimum at the final stage of production, in the “cut-make-trim” factories, this does not extend to the textile workers, who spin or embroider the fabric, or to the cotton farmers at the very beginning of the supply chain.

The latter certainly deserve better treatment. In the past 15 years, there have been 250,000 cotton-farmer suicides in India (equivalent to one every 30 minutes) because they simply can’t make ends meet. But, says Somers: “Tragedies are preventable. All we need is to make every stakeholder in the fashion supply chain responsible and accountable for their action and impacts. We have incredible power as consumers, if we choose how to use it.”

The 63-million reach of last year’s #whomademyclothes hashtags is just a first step.

Lizzie is the author of London's ethical fashion and food website, bicbim.co.uk. Follow her on Twitter @LizzieRivs and @bicbim.

Find out more about: Fashion Revolution.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments