Northern Soul: 40 years later the scene is bigger than ever

Britain has excelled at creating eccentric groups, each with its own strict code of dress, music and manner. Until now. Here, the former 'soul boy' Chris Sullivan wonders why

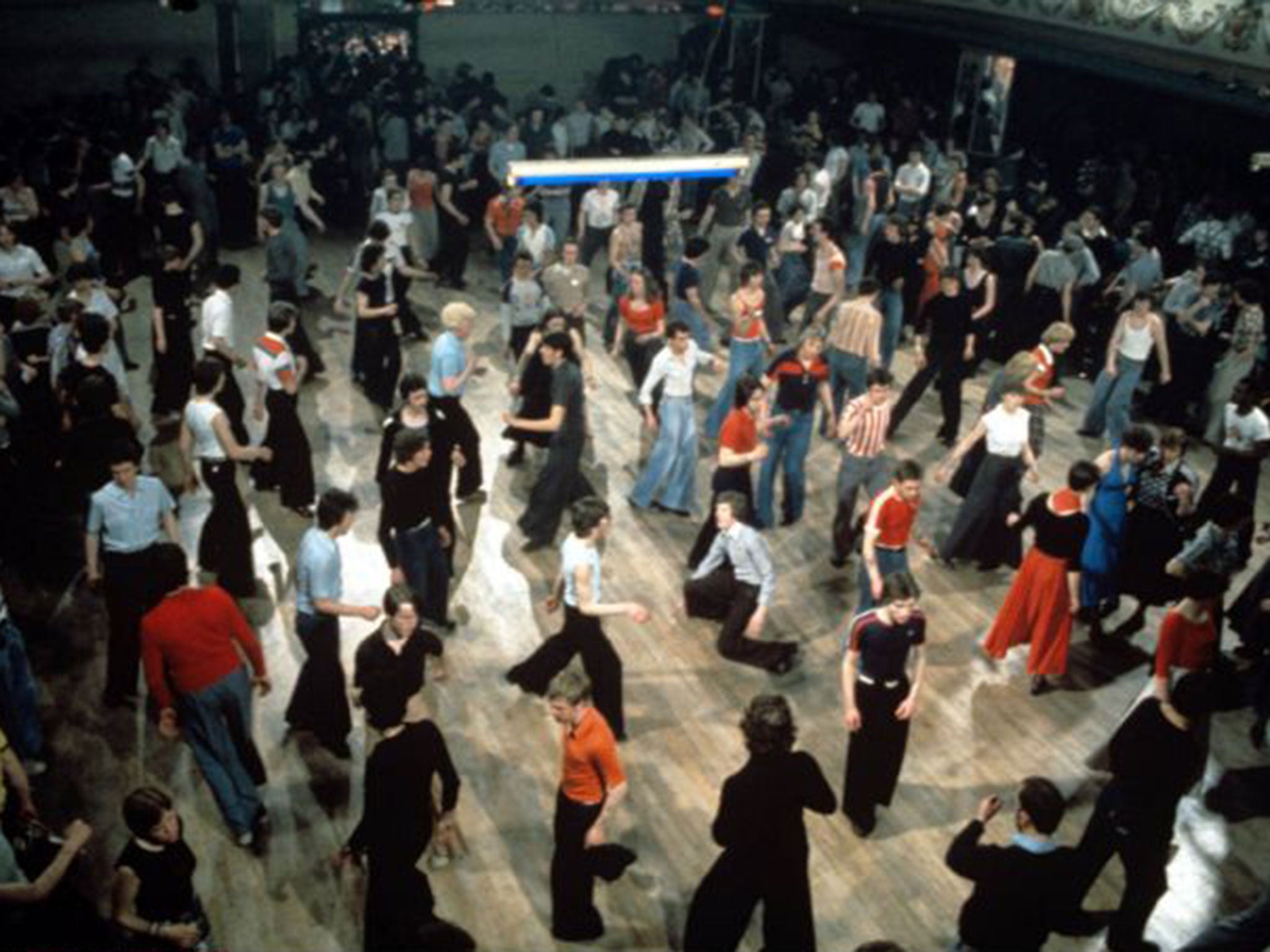

It is a rainy Sunday afternoon in Birmingham and 200 or so young people pack the dance floor of the Testify Northern Soul All Dayer. To the last, they face the DJ, shuffling from side to side like a gaggle of Whirling Dervishes before clapping their hands in unison and breaking into spins, splits and backdrops. The men wear brogues, baggy trousers, vests and Fred Perrys, while the women are in wide skirts and flat shoes. This is just one of 26 recent Northern soul events, held across the UK as part of the "All Weeker" calendar that celebrates the release of Northern Soul, the bravura feature debut by director Elaine Constantine, and its soundtrack CD.

Becki Sabell, 26, who attended the event, says that the Northern soul scene is bigger now than ever. "The main thing I love about the Northern soul scene is the sense of community," she says. "Everybody coming together over the love of the same music is ace."

Constantine's film, set deep in the dour industrial North of 1974, takes place against the backdrop of that most beguiling and eccentrically idiosyncratic of all British style tribes – Northern soul – which, based around dancing all night (and sometimes all day) in ballrooms to rare Sixties and Seventies US black soul 7in singles, baggy trousers and bundles of speed, is about as British, in its own peculiar way, as Morris dancing. The film stars Elliot James Langridge as John Clark, a teenage misfit who stumbles across the fascinating youth cult after meeting a fledgling DJ (Josh Whitehouse) and, much to his parents' chagrin, bewilderment and utter frustration, becomes obsessed with the soul scene's every nuance, learns the moves, swallows the obligatory amphetamines, sees the dark side and, thus, comes of age. The film, proudly "kitchen sink" in its ambitions, recreates the scene exactly as it was. I know because I was there.

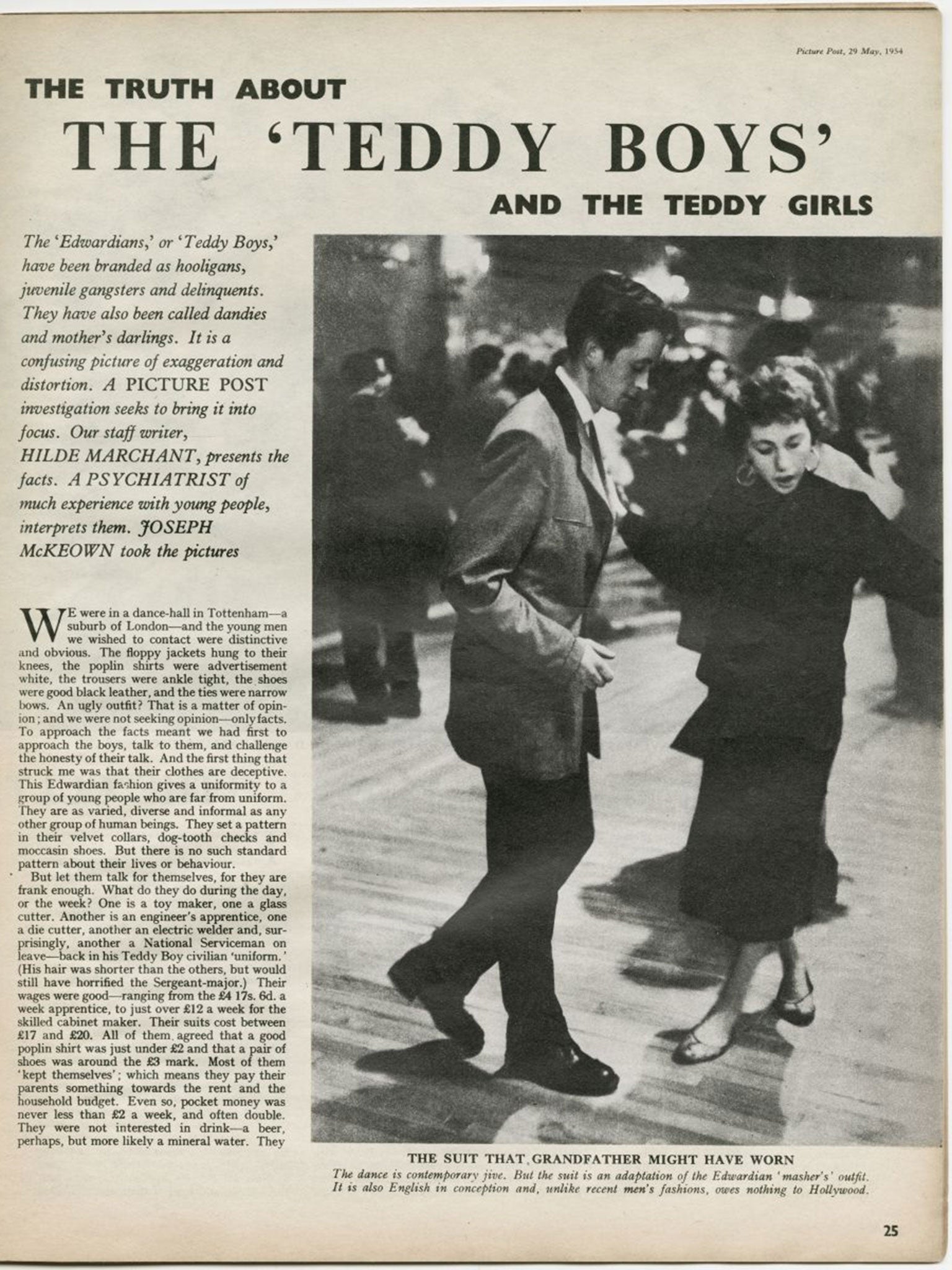

And yet, as authentic as it certainly is (down to the sweat and spit of the hundreds of dancers recruited by Constantine from all over the country), the film might well have told the tale of a new Teddy boy, mod, hippie, punk or new romantic – all of whom would have spent their last pound on exotic threads and arcane vinyl while their parents banged their heads against their pebble-dashed homes and turned to drink. As a 16-year-old mod named Susan from London was quoted as saying in the 1965 book Generation X, "You'd really hate an adult to understand you. That's the only thing you've got over them – the fact that you can mystify and worry them."

In essence, the Northern Soul film conveys that very special time when we, as teenagers, discover our very first scene, which, replete with its own music, fashion and attitude, we totally and unequivocally adore above and beyond everything – and everybody – else. "We all go through it and it's a very important time in our lives," says Paul Weller, who is no stranger to the style tribe." I remember seeing all these mods hanging around Woking, where I grew up, and was fascinated. That stuck with me.

"My entry point into style and music was in the early Seventies when we were suedeheads – little peanuts – with the button-down shirts and loafers dancing to ska," he adds. "That was the common ground and I loved it. It was a way for people who haven't got much money to make a show. It gave us our identity that was different from the rest. One look and you knew what someone was into and what music they liked. It's a Great British working-class tradition that began in the Fifties with the Teds."

It is entirely appropriate then that Northern Soul, a film that fundamentally scrutinises and applauds this conceit, should be released in 2014 because it was 60 years ago that the first image of a British youth using sartorial style as a means of personal rebellion appeared in print on the cover of Picture Post, then Britain's favourite magazine, in May 1954. The photograph of Frank Harvey, a rather nonchalant north London teenager decked out in full "New Edwardian" (Teddy boy) regalia hit the newsstands nationwide, prompting a wave of copycat Teddy boy teenagers (whose older brothers had dressed like their dads) and immense resentment from their parents, and changed the nation for ever. Without a doubt, that image hit the zeitgeist square on the nose.

A few months earlier, Brando's controversial biker film, The Wild One, had been banned in the UK. Then, just a few months later, on 19 July, Elvis released "That's All Right", while Bill Haley's "Shake, Rattle and Roll" hit the US charts in August. Rock'n'roll was born and with it came teenage rebellion that, hand-in-hand with its own culture and doting style tribe, came a-kicking and a-screaming and a-scaring the shit outta parents from Sacramento to Sunbury-on-Thames.

And, of course, it is the Brits who have forever excelled in the creation of eccentric and bafflingly idiosyncratic style tribes. The granddaddy of all post-war UK style tribes – the aforementioned Teddy boy – came about after a gang of teenage ne'er-do-wells (such as Brian McDonald and Charlie Richardson) from London's Elephant and Castle clocked gangs of predominantly homosexual ex-guardsmen and gathered on Savile Row wearing what was christened The New Edwardian look. A blatantly extravagant breach of the post-war austerity measures, the style was, as George Melly states in his book, Revolt Into Style, "a fair symbol of class privilege".

Of course, this was exactly what attracted these hatchling villains and, rather like some petty 21st-century criminal who indulges himself in designer bling, they, too, had to enjoy exactly the same chattels as their so-called betters. So off bowled the wily teenagers to Hymie the tailors in The Cut in Waterloo to get that special and rather costly bespoke suit. In their unbridled enthusiasm, they added the excesses of the spiv as they remembered it, threw in a bit of zoot and a pinch of Western wear and created the Teddy boy silhouette. Hymie's son, Grayson, now 84, who worked in the store, recalls that the Edwardian style came in after all the local kids ordered it. "We did suits with velvet collars and very tight trousers with no pleats or turn-ups," he says. "Of course, the teenagers who wore these were all over the papers because they were the first youngsters to look like proper rebels. And they really were rebels in every sense. The whole outfit from top to bottom would cost three months' wages. We never asked where they got the money from, but it wasn't from their parents."

Subsequently, reactionary British-style tribes have been legion. In the Sixties alone, we saw rockers (AKA ton-up boys) who reached back to The Wild One for their greasy motorbiking mores, sharp-suited mods who exchanged amphetamines for the parkas of visiting US servicemen, and the hippies who reacted against both the mods and their middle-class besuited fathers by growing their hair long, and wearing sandals and beads. And that is what youth culture is all about. Action – reaction, push – pull. Long hair followed by short hair. Narrow pants, then wide pants. Kids doing the exact opposite of their contemporaries.

Kevin Rowland, the Dexy's singer, remembers 1969 as having scruffy hippies everywhere. "And I certainly didn't want to look like one," he says. "I was working class and wanted to dress up and look smart. So we did the exact opposite of the hippie and tried to look like an American servicemen from the Mid-West – Ivy League style – which was really, really subversive because it was so conservative compared with the entire hippie-dippy fashions. Hair was short back and sides, shoes were Gibson's, and the Harrington was the jacket while older boys wore Sinatra-style trilbies and mackintoshes. This was what the media called 'skinhead'. I was 16, wore the gear and had the haircut. It was my time and I was gonna take it."

Rowland was not alone. This Great British teenage recalcitrance has since produced an intoxicating parade of style tribes: glam, punk, casuals, new romantics, goths, Sloanies, psychobillies, B-boys and fly girls, ravers, cyberpunks, skaters, crusties, grungers – each one a reaction against the style before with their own distinct code of dress, music, language and manner. All have filled the front pages of newspapers and entered the national psyche and the dictionary while going out of their way to confound and confuse the rank and file.

"It's what we do best," the singer Adam Ant tells me with a chuckle, "and we always go against the grain – long-haired hippies, short-haired skins. British youth cults are a fundamental part of out national psyche. But we don't see much of it any more. We don't see many new tribes these days. No one stands out any more."

Indeed, compared with the past, there's been a paucity of new-style tribes in the 21st century. Of the few names bandied about, there have been "boffins", pin-ups" and "bunker boys". The latest is, of course, the lambasted "hipster", which isn't a style tribe at all but simply a catch-all moniker for a generation of bearded men who like coffee and are happy to follow, and not buck, trends. Sheep is a far superior appellation. Call me old-fashioned, but fashion trends follow style tribes long after those who started them have moved on. Many designers simply repackage and refine cult items and then sell them on to those who don't know any better. That is the antithesis of youth culture.

Even more puzzling is that today most young people seem content to wear a rather ironic printed T-shirt, low-slung jeans and trainers. They seem entirely unaware that our clothing is our first form of communication and might actually do them a favour. That is why past style tribes used clothes to make a statement. Clothing is how we are judged. But do people care these days? Have they found other ways to make themselves heard or would they rather remain silent and sit on the fence? Perhaps, if Johnny (Marlon Brando's character in The Wild One) were asked today, "What are you rebelling against?" He might say 'Not a lot!"

"People don't seem to want to express themselves with their clothes any more," says Soho tailor Mark Powell in a chiding tone. "They just put clothes on and don't dress up or dress down. For me, the attractions of being a young suedehead and then a soul boy, for example, was finding that item that you travelled miles to get, said something about you personally and, as a result, made you feel really special when you wore it. Today, everything is so accessible on the internet that maybe the buzz has gone. It's hard to feel special in an item that is itself not that special or unique or mutinous."

I guess it is difficult these days for teenagers to rebel against their parents who smoke the odd spliff of an evening, drop a pill at the weekend and spend outrageous amounts on a pair of jeans. I was extremely fortunate. My mum wore a pinafore all day long and drank cocoa (albeit laced with Carnation).

Luckily, for us style-mongers, there is one scene that is thriving and that's Northern soul, which, despite being more than 40 years old is still attracting new adherents. Constantine's film sums up the effect. Initially, it was to screen in only a handful of major cities but demand fuelled by social-media sites has propelled it into 125 cinemas all over the UK – many of which are already sold out.

"I am surprised by the reaction," says Constantine, "But there are a lot of young people who've had enough of bad pop music and conforming to high-street trends, and are turning to Northern because it's about people who are passionate about great music and it's a real scene with its own way of dress and club nights. There seems to be a huge sense of belonging among this scene that stretches all over the country. I think folk like being a part of something that's a bit special again."

'Northern Soul' is on general release now; northernsoulthefilm.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments