Geeks who rocked the world: Documentary looks back at origins of the computer-games industry

For one moment three decades ago, the British computer-games industry was a few thousand kids with a cheap computer, a tape recorder and a punk-like passion for the mysteries of programming. As a retro version of the ZX Spectrum gears up for release, Rhodri Marsden charts the rise and fall of the video-game punks

During the early days of Thatcher's Britain, a suburban branch of WH Smith was one of the last places you'd expect to have a Damascene awakening. But an act of creative disobedience in the stationery section meant that a small TV screen could display the phrase "WH SMITH IS SHIT" over and over again, filling the screen and displaying an error code at the bottom. The computer attached to it, a ZX81 with a mere 1k of memory, had run out of screen space – but it had done exactly as instructed by the miscreant:

10 PRINT "WHSMITH IS SHIT ";

20 GOTO 10

The creator of this program knew what its effects would be, both on and off screen. Eventually, when noticed by a long-suffering member of WH Smith's staff, the machine would be rebooted. But in the meantime it would be seen by dozens of kids, who realised that computers weren't just the inherently tedious playthings of the bearded electronics enthusiast. They could be made to misbehave, to confound and entertain. These moments of inspiration would, in the years that followed, see the UK punch well above its weight in the global video-games market. Titles such as Grand Theft Auto and Tomb Raider can, through convoluted family trees, trace their roots right back to the phenomenal level of curiosity that home computers provoked in the early 1980s.

Some five years before the launch of the ZX81 in 1981, the spirit of punk had seized the young people of Britain as they realised that the means of musical production was available to them all; as the Desperate Bicycles put it: "It was easy, it was cheap, go and do it!" Home computers presented kids with a similar opportunity: you could, if you had a good idea and enough programming knowledge, make thrilling stuff happen on people's television screens, not only across the country but across the world. "We were the quiet ones," says Jason Kingsley, co-founder of games developer Rebellion and chairman of UK games industry body Tiga. "In our understated way, we were rebelling just as much in the background as the punks were on stage."

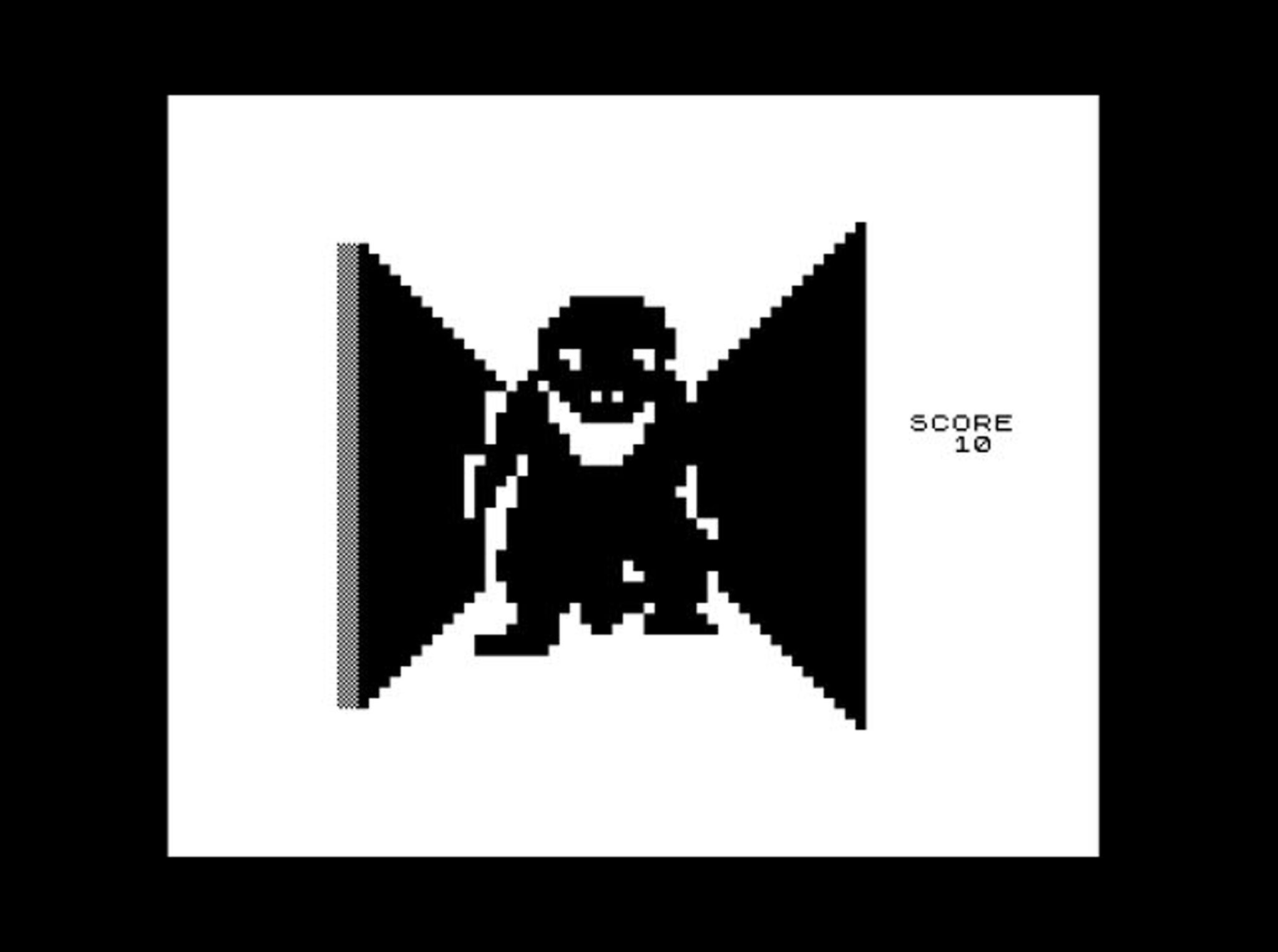

Arcade and console games had already been knocking around for a few years, but you could play only what you were given. Computers allowed you to make the game yourself – though in the early days their graphical capabilities were hilariously limited. For example, if in 1977 you had bought a £40 MK14 computer kit from Science of Cambridge, you could have programmed it with an accompanying listing for a game, Moon Lander, which consisted of eight digits changing occasionally. But by 1981 there were machines, including the ZX81, the VIC-20 and the Acorn Atom, which were affordable and able to run games with graphics, albeit rudimentary. A ZX81 game such as 3D Monster Maze, with its blocky representation of a Tyrannosaurus Rex, looks slightly absurd today, but back then represented a formidable achievement.

"Obviously the British didn't invent the video game," says Anthony Caulfield, director of From Bedrooms To Billions, a new film about the early days of British computer gaming. "We were massively influenced by Japanese and American arcade machines. But there is something ingrained in the British psyche about messing about with electronics, tinkering away, getting things working. And getting as close as we could to arcade games is how we became such great programmers."

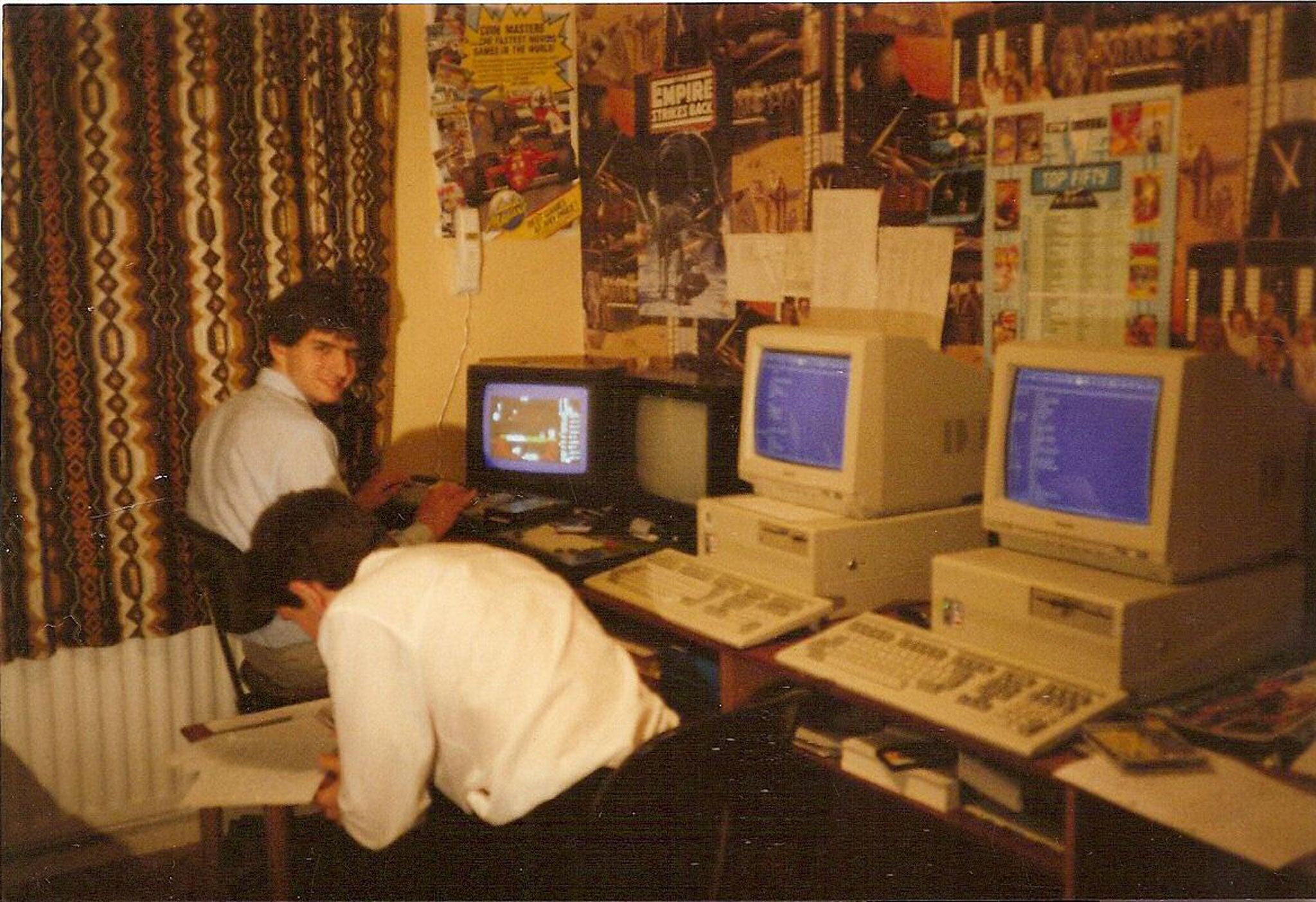

The burgeoning movement was overwhelmingly driven by British kids, who persuaded their parents to part with hard cash to buy those machines and their successors, such as the ZX Spectrum, BBC Model B and Commodore 64.

"I think mum and dad probably knew that you'd end up playing games on them," says Tiga's Kingsley. "But there was a plausible deniability; they could tell their peer group, well, we've got them a little computer and they're programming all sorts of very important things. In fact, we were typing out code from magazines to play a version of Space Invaders." With intense hunger for entertainment but with few games available commercially, young enthusiasts would get their gaming kicks from these magazine listings, which had to be laboriously typed in.

"I remember going to the local college library and hoovering up all the magazines on the shelves," says Philip Oliver, who, with his twin brother Andrew, would go on to create the phenomenally successful Dizzy arcade-adventure series. "It was a time-consuming exercise, but it was a magical feeling. You were making something, you were discovering something new. And you didn't have to buy components! With Lego and Scalextric, you always had to buy more stuff; with a computer, you could just get on with it."

If the listing didn't work, you would have to wait a month for the magazine to print the corrections in the next issue. "Or," says Kingsley, "you'd debug it yourself. That delay with magazine publishing was critical. It provided us with the motivation to fix the damn thing." Many would see that as an act of drudgery, but Oliver stresses the creativity needed to wade into the code. "I'll argue that to my grave," he says. "You had to be incredibly creative to solve problems in the most elegant way. It was a real art."

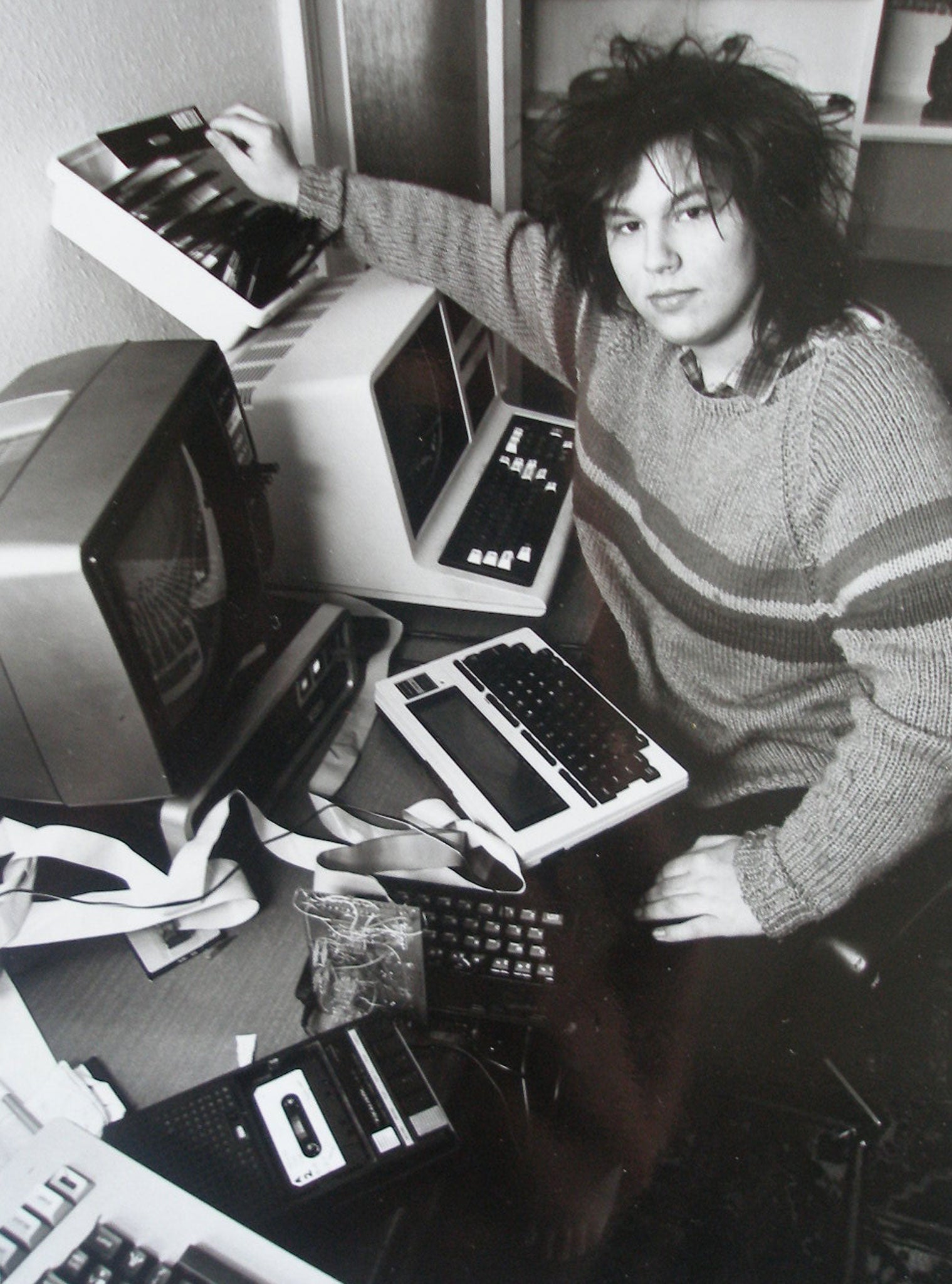

A whole generation, many of whom would never have previously classed themselves as creative, were suddenly bestowed with a punk-style empowerment; they could actually write a game from scratch. "This was going on all over the UK," says Caulfield. "No one knows how many were doing it, but judging by the number of classified adverts in computer magazines, we reckon it must have been between 10,000 and 50,000 young people." (Those people being, almost overwhelmingly, young boys.)

In 1982, there was an extraordinary surge in ad-hoc, spontaneous business, all completely under the radar of corporate Britain. With no high-street retail outlet for computer games, demand completely outstripped supply. As a consequence, kids with varying levels of programming skills stepped in to soak up the demand via mail order. Prompted by magazine advertising alone, thousands upon thousands of cheques for a fiver or so were sent to home addresses across the UK. Cassettes were duplicated, covers were photocopied, product was popped into a Jiffy bag and posted, the punk spirit of DIY reignited.

Some of the games were dreadful – but plenty were not. Computer fairs, held regularly across the UK, were suddenly packed with people looking for games to play. Rod Cousens, now chief executive of games developer Codemasters, recalls in From Bedrooms To Billions a visit to the Northern Computer Fair in 1982, where his newly formed company took so much cash at one stall that in the evening they found themselves throwing it around their hotel room in disbelief.

Independent shops opened, such as Buffer Micro in Streatham, south-east London, and Just Micro in Sheffield, weekend hang-outs for games obsessives; Just Micro would later transform into Gremlin Graphics, Gremlin Interactive and ultimately Core Design, the creator of Tomb Raider.

But with low unit costs, high margins and large sums being made, it wasn't long before the parasites moved in. By 1984, much of the DIY spirit had been dampened by unscrupulous business types. "There was no trust," says Mo Warden, who began working on games as an unemployed young mother. "And it was a hard lesson. People were doing amazing things, but far too many people were sitting in offices being 'important' and making lots of cash, while those creating it obviously weren't."

Kingsley agrees. "As with punk, a lot of people were young and were horribly exploited. The artists themselves often didn't make any money and weren't happy." The most notable example was Matthew Smith, the young creator of Manic Miner, one of the most original British titles of all time. "He made a lot of money from that," says Caulfield, "but almost immediately he was required to turn another game [Jet Set Willy] around in six weeks, before Christmas. And because he was under pressure, he started to crack. The British industry started to suffer because there was this need to get product out constantly." Little wonder that many of those k early coders became disillusioned and started to drift away from the business. But many others, of course, stuck with it, becoming hugely successful and laying the foundations of one of Britain's most successful industries.

Young coders of today have digital devices in their possession whose capabilities would have caused an 11-year-old back in 1981 to pass out in shock. While cheap machines such as Raspberry Pi still offer a low-cost introduction to the world of programming, the landscape has changed unimaginably over the past 30 years. Even aside from the technology, we now live in a cynical age where it's impossible to imagine a fragmented, spontaneous grass-roots movement achieving any level of independent commercial success.

Yes, the app revolution has given people an opportunity to create their own games once again, and in some instances – most notably the surprise hit Flappy Bird – they've achieved global recognition with very limited resources. But the Oliver twins, whose latest creation is the online game Sky Saga, equate success in the app world with winning the lottery. "The criteria for success is completely random," says Philip, "and I worry that people are investing time and money in something that won't yield very much."

Kingsley agrees. "[Success with an app game is] more about discoverability, eyeballs and business speak than creating something beautiful just because you can."

There's a fierce, low-level nostalgia for those early 1980s computers, machines that sold millions of units in the UK alone. Crowdfunding site Indiegogo has, in recent weeks, raised £125,000 for the production of the ZX Spectrum Vega, a new eight-button gaming machine based upon the original Spectrum with thousands of retro games pre-loaded.

But while the outward ripples from our early interest in computer gaming have touched more people than the Sex Pistols et al ever will, that initial British gaming explosion is often overlooked – in the meantime, punk music is constantly cited as a pivotal moment in British culture. "A lot of people don't understand how much power you can have if you know how computers work," says Kingsley, "and the only thing you can do in that situation is to assume it's not important and belittle it.

"We didn't know it was important at the time. It's only with hindsight that you realise just how influential it was in terms of setting things up for the digital future. But none of us were doing it deliberately. We were just having fun."

'From Bedrooms To Billions' is available to view online now at frombedroomstobillions.com

High scores: Games that levelled up

'Football Manager'

While emptying bins for the council, Kevin Toms saw an advert for a ZX80 and sent off for one on impulse. With tremendous foresight, he saw a gap in the market for a football-management simulation game; he created Football Manager for the ZX81, which spawned a number of sequels. The genre continues to be hugely popular.

'Jetpac'

Tim and Chris Stamper, described as the "Gilbert and George of the computer game world", brought arcade-standard gaming to the ZX Spectrum, VIC-20 and BBC Micro with Jetpac. The first title in the Ultimate Play The Game series, it raised the bar in terms of slick graphics and addictive gameplay.

'Elite'

David Braben and Ian Bell's space-trading game for the BBC Micro was highly influential. Its wireframe graphics and open-ended game model would inspire a generation of games programmers, who took these ideas forward into titles such as Wing Commander and Grand Theft Auto.