The one-armed robot that will look after me until I die

In future, it seems inevitable that the elderly and infirm will be looked after by machines. But how far are we down that road and will we like it?

The game is simple, designed for a child and intended to teach users about diet and diabetes. I sit opposite Charlie, my diminutive fellow player. Between us is a touch screen. Our task is to identify which of a dozen various foodstuffs are high or low in carbohydrate. By dragging the images we can sort them into the appropriate groups.

Charlie is polite, rising to greet me when I join him at the table. We proceed, taking turns, congratulating each other when we make a right choice and murmuring conciliatory comments when we don’t. It goes well. I’m beginning to take to Charlie.

But Charlie is a robot, a two-foot-tall, glorified computer. It may move, it may speak, but it is what it is: a machine that looks humanoid. How can I ‘take’ to it?

Charlie’s intended playmates aren’t sixty-something Englishmen, they’re children. Children naturally interact with dolls, imagining them to be sentient beings. It’s a part of childhood. But I’m an adult, for God’s sake. I should have put away such responses to dolls… shouldn’t I?

In truth my reaction to Charlie, far from being odd or childish, is pretty typical. Robots, of course, are hardly new but the 2010s have seen a rise in the attention paid to autonomous machines that can sense their surroundings, respond, move, do things and, above all, interact with us humans. We all recognise R2-D2 and WALL-E; the unnerving thing is that their nonfictional counterparts are extremely close at hand – and intended to help us cope with disability and old age.

This has set me wondering how I might cope with the experience – not for an hour or a day, but for months, years. Very soon, I will have to get used to the idea of living with robots, most likely when I’m elderly and/or infirm. And my line of thought has both surprised and disturbed me.

Modern medicine and increasing longevity have conspired to boost the need for social care, whether in the home or in institutions. Traditionally among the poorest paid of the workforce, carers are an ever more scarce resource. So policy makers have begun to cast their eyes towards robots as a possible source of compliant and cheaper help.

Indeed, they’re already in production, says Tony Belpaeme, Professor in Intelligent and Autonomous Control Systems at Plymouth University. Principally geared to monitoring the elderly and infirm, or providing companionship, as yet, they perform only the most straightforward of physical tasks. But wait… companionship? “Yes,” says Belpaeme, deadpan, “Of course it would be better to have companionship from people. [But] studies have shown that people don’t mind having robots in the house to talk to. Ask the elderly subjects who take part if they’d like to have the robot left in the house for a bit longer, and the answer is nearly always yes.”

Consider our relationship with nonhuman entities of a different type: animals. When medical researchers started to take an interest in the health effects of pet ownership they began to find all sorts of beneficial consequences – physical as well as mental – including reductions in distress, anxiety, loneliness and depression, as well as a predictable increase in exercise. Pets seem to reduce cardiovascular risk factors such as serum triglyceride and high blood pressure.

The pleasures of animals as companions – and the real distress that may follow their loss or death – are self-evident, and research in Japan has revealed a biological and evolutionary basis to the relationship. Scientists there measured the blood levels of oxytocin in dogs and their owners, had them gaze at one another for an extended period, and then repeated the measurements.

If you already know that oxytocin is the hormone associated with building a bond between mothers and their babies, you’ll guess where this is going. The researchers found that periods of mutual eye contact raised the oxytocin levels in both parties. In short, they uncovered the physiological basis of loving your dog.

Whether on account of chemistry or for other reasons, there is evidence that the majority of pet owners see their animals as part of the family. “This doesn’t mean they regard them as humans,” says Professor Nickie Charles, a University of Warwick sociologist with a particular interest in animal-human relationships. Close links with animals are often in addition to rather than instead of relationships with family and friends.

The suggestion that non-living things, including robots, might be able to evoke human responses that are comparable to our feelings about animals is contentious. Yet the evidence suggests this is the case, even if we might not admit it or feel faintly uncomfortable when we do. But who hasn’t shouted at a failing machine? And if you imagine such behaviour is simply the relief of pent-up tension or anger, think back to the mid-1990s and the advent of the tamagotchi, according to the maker “an interactive virtual pet that will evolve differently depending on how well you take care of it.”

Also from Japan is the PARO – modelled on a baby harp seal, weighing a couple of kilos and slightly larger than a human infant – which made its debut more than a decade ago, and has sold nearly 4,000. Covered in soft white fur, PARO responds to touch, light, temperature and speech sounds – as I discover when I try stroking and even talking to the creature sitting on the table in front of me. It turns its head to me when I speak; it emits seal-like squeaks when I stroke it; and when ‘content’, it slowly lowers its head and closes its big appealing eyes, each kitted out with seductively long thick lashes. This blatant emotional manipulation is accentuated when I pick PARO up; cradled in my arms, it begins to wriggle as I go through my talking and stroking routine.

I encounter PARO at the London offices of the Japan Foundation, where it has accompanied its inventor, Takanori Shibata, an engineer at the Japanese National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology. Shibata categorises PARO’s benefits under three headings: psychological (it relieves depression, anxiety and loneliness), physiological (it reduces stress and helps to motivate people undergoing rehabilitation) and social. In this last category, he says, “PARO encourages communication between people, and helps them to [interact with] others” – social mediation, to use the technical term. As Shibata points out, “PARO has many of the same effects as animal therapy. But some hospitals do not allow animals because of a lack of facilities or the difficulties of managing pets.” Not to mention worries over hygiene and disease.

Much of the evidence of the benefit from PARO is based on informal observation (though there have also been more controlled trials). In one pilot study, three New Zealand researchers investigated a small group of residents in a care home for the elderly. Each resident spent a short period handling, stroking and talking to a PARO. This activity triggered a fall in blood pressure comparable to that following similar behaviour with a living pet.

In my brief period handling PARO, I can’t say I felt anything more than mild amusement – and certainly not companionship. Dogs and cats can do their own thing; they can ignore you, bite you or leave the room. Simply by staying with you they’re saying something. PARO’s continuing presence says nothing.

But then I’m not frail, isolated, lonely or living in a care home. If I were, my response might be different, especially if I was nearing the onset of dementia, one of the conditions for which PARO therapy has generated particular interest.

Among, for example, Amanda Sharkey and colleagues at the University of Sheffield. But the calculated use of a PARO for companionship she actually finds worrying. “It could be misused in a care home by thinking, ‘Oh well, don’t bother to talk to her, she’s got the PARO, that’ll keep her occupied…’”

But now I’m in Hatfield, Hertfordshire, in an apparently normal house in a residential part of town – where I’m confronted by a chunky greeter, just below my shoulder height. Its black-and-white colour scheme is faintly penguin-like, but overall it reminds me of an eccentrically designed petrol pump. It’s called a Care-O-bot. It doesn’t speak, but welcomes me with a message displayed on a touch screen projecting forward from its belly region.

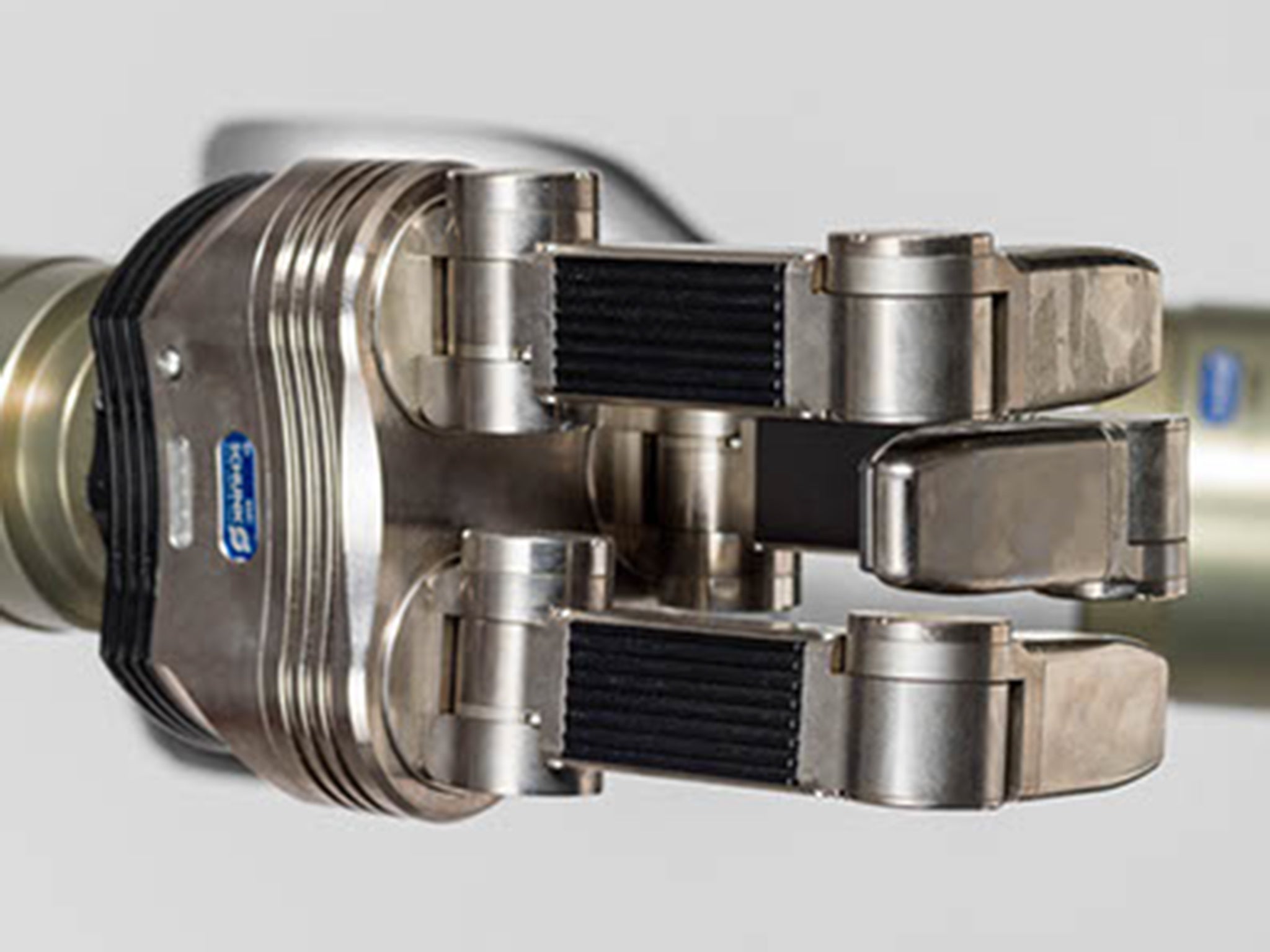

Care-O-bot asks me to accompany it to the kitchen to choose a drink, and then to take a seat in the living room, while it follows with a bottle of water carried on its screen, now flipped over to serve as a tray. It glides silently forwards on invisible wheels, performing a slow and oddly graceful pirouette as it confirms the location of people and objects within its domain. Parking itself beside my table, Care-O-bot unfurls its single arm, grasps the bottle and places it (almost) in front of me.

The building is owned by the University of Hertfordshire, and its ordinariness is, of course, an illusion. It’s actually bristling with sensors and cameras – and it’s this, rather than my box-shaped companion, that I find more perturbing. Also monitored are the activity of kitchen and all other domestic appliances, whether doors and cupboards are open or closed, whether taps are running – everything, in short, that features in our activities of daily living.

Even so, as Tony Belpaeme points out, current robots don’t have the skills that are most needed: the ability to tidy houses, help people get dressed and the like. These things, simple for us, are tough for machines. Still, newer Care-O-bots can at least respond to spoken commands and speak themselves; and that’s a relief because, to be honest, it’s the silence I find most disconcerting. I don’t want idle chatter, but a simple declaration of what my Care-O-bot’s doing or about to do would be reassuring.

So would I find an advanced version – one that really could fetch breakfast, wash-up and make the beds – difficult to live with? I don’t think so. But what of more intimate tasks – if, for example, I became incontinent? Would I cope with Care-O-bot wiping me? If I had confidence in it, I think so. It would be less embarrassing than having the same service performed by another human.

After much reflection, I think adjusting to the physical presence of a robot is the easy bit. It’s the feelings we develop about them that are more problematic. But if dogs, cats, robot seals and egg-shaped key rings can so easily evoke them, why should I be exercised about it? After all, we don’t generate angst about children forming such relationships with dolls, imaginary friends and the like. And what’s more, I seem to be setting my face against science.

“I don’t see why having a relationship with a robot would be impossible,” says Belpaeme. “There’s nothing I can see to preclude that from happening.” The machine would need to be well-informed about the details of your life, interests and activities, and it would have to show an explicit interest in you as against other people, he says, but he can envisage a time when one might.

Kerstin Dautenhahn, Professor of Artificial Intelligence at Hertfordshire, hopes that robots never become a substitute for humans. “I am completely against it,” she says, but she concedes that if that’s the way technology progresses, there will be little that she or her successors can do about it. “We are not the people who will produce or market these systems.” As for Belpaeme, his ethical sticking point – and others usually say something similar – would be the stage at which robot contact became preferred to human contact. But in truth, that’s not a very high bar. Many children already trade many hours of playing with their peers for an equivalent number online with their computers.

In the end, of course, the question becomes not do I want a robot companion to care for me, but would I accept being cared for by a robot? If the time comes when I am still compos mentis but physically infirm, would I be prepared for the one-armed Care-O-bot to take me to the toilet, or PARO to be my couch companion during movies?

Well, on a simple level of practicality there’s a way to go before any robot has the communication skills, dexterity and versatility of even the most cack-handed human. But assuming the engineers overcome this hurdle, I’m back to the question of companionship. Life devoid of it is sterile – so the fact we tend to form bonds, even with robots, is in principle encouraging. But companionship, to my mind, incorporates three key requirements: physical presence, intellectual engagement and emotional attachment.

The first is not an issue. But the second has yet to be cracked. True, artificial intelligence is moving rapidly: in 2014 a chatbot masquerading as a 13-year-old boy was claimed to be the first to fool humans into thinking that it, too, was human. Even so, the biggest hurdle to a satisfying conversation with a machine is its lack of a point of view. This requires more than a capacity to formulate smart answers to tricksy questions, or to randomly generate the opinions with which even the most fact-laden of human conversations are shot through. A point of view is something subtle and consistent that becomes apparent not in a few hours, but during many exchanges on many unrelated topics over a long period.

Which brings me to the third and most fraught ingredient: emotional attachment. I don’t question this on feasibility counts because I think it will happen anyway - but the quality and meaning of such attachments are the key issues here. As an ardent materialist I don’t accept that living things incorporate some ingredient preventing them from being explained in purely physical and chemical terms. So if silicon, metal and complex circuitry were to generate an emotional repertoire equal to that of humans, why should I make distinctions?

To put it baldly, I’m saying that in my closing years I would willingly accept care by a machine, provided I could relate to it, empathise with it and believe that it had my best interests at heart. But that’s the reasoning part of my brain at work. Another bit of it is screaming: What’s the matter with you? What kind of alienated misfit could even contemplate the prospect?

So, I’m uncomfortable with the outcome of my investigation. Though I am persuaded by the rational argument for why machine care should be acceptable to me, I just find the prospect distasteful – for reasons I cannot, rationally, account for. But that’s humanity in a nutshell: irrational. And who will care for the irrational human when they’re old? Care-O-bot, for one; it probably doesn’t discriminate.

A longer version of this article first appeared on mosaicscience.com. It is published here under a Creative Commons licence

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks