Who owns your e-book?

You've bought a book for your e-reader and it's yours to own, right? That's what George Orwell fans thought, until their purchases disappeared. The implications are sinister, discovers Simon Usborne

Justin Gawronski, a 17-year-old American student living outside Detroit, had spent several weeks studying George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four when, one morning last July, Amazon ate his homework. He woke up and switched on his Kindle electronic reader only to watch the copy of the dystopian novel he had bought three months earlier disappear. "I was quite upset the moment it happened," Gawronski recalls in an email. "I certainly never expected something that I bought and thought I owned could be taken away from me so easily."

Gawronski wasn't the only victim of what would become known among some outraged bloggers as the "Kindle swindle". When Amazon realised copies of two Orwell books – Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm – had been added to the Kindle store by a company that did not have rights to them, it removed the books and hit the delete button. Next time users who had bought a copy logged on to Whispernet, the wireless service through which Amazon delivers all its e-books, their copies self-destructed. Customers commenting on online forums had previously reported the disappearance of digital editions of the Harry Potter books and the works of Ayn Rand over similar issues.

Online commentators had a field day when news of the Orwell incident flashed across the web. Here was the world's biggest bookseller effectively walking into its customer's homes under the cover of darkness and removing books from their shelves. And it couldn't have happened to a better novel. In Nineteen Eighty-Four, books that don't meet the approval of the totalitarian regime are thrown down an incineration chute called the "memory hole". By "disappearing" Nineteen Eighty-Four, albeit for less sinister reasons (customers were refunded), Amazon has triggered a wider debate about what it means to own books, music or film in the digital age.

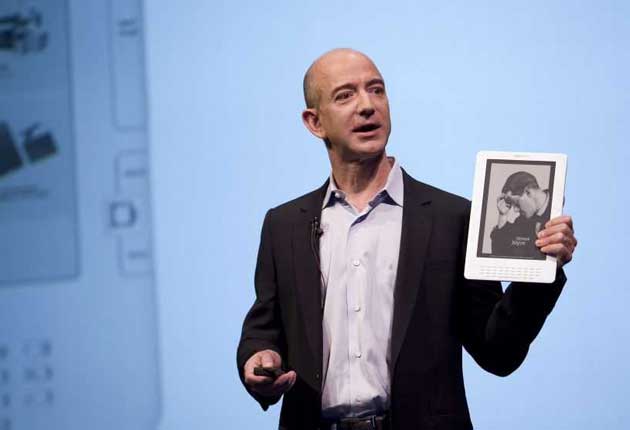

And if we are to believe, as many do, that e-readers are the future of publishing, this really matters. In Britain, Waterstone's now has 20,000 books compatible with Sony's Touch and Pocket devices, as well as the iRiver Story. Amazon started shipping its Kindle to Britain and 100 other countries last October and also offers the service on the Apple iPhone. Last month Amazon's chief executive, Jeff Bezos, revealed that the Kindle store now stocks more than 350,000 books. More tellingly, Bezos said that, for titles also available in print, Amazon sells at a ratio of 100 real books to 48 digital books. "It won't be long before we're selling more electronic books than we are physical books," he told the New York Times Magazine. "It's astonishing."

But when we increasingly buy books and music that exist only as files, what does it mean to own them? When you walk into your local bookshop or even hit "proceed to checkout" on an online store, you are not forced to sign a contract before you get your copy of Animal Farm. Even if the paper-and-glue book turns out to have legal issues, a shop may be ordered to stop selling them but its customers can't be compelled to return their purchases – because they own the books.

But things are different online. When you pick up a book for your e-reader, you are not so much buying an object as a service and, as the Amazon Kindle "license agreement and terms of use" says, "Amazon reserves the right to modify, suspend, or discontinue the Service at any time, and Amazon will not be liable to you should it exercise such right." The small print you agree to when you sign up with Sony's service or Apple's iTunes store gives them similar rights over "your" stuff. It's part of Digital Rights Management (DRM), the system that also stops you carrying your iTunes music library to more than five computers, lending a friend your e-book as you might a real one, or copying a DVD to your computer.

Amazon's response to the outcry over its Orwellian move was as swift as it was sheepish. In a statement posted on the website, Bezos said the remote removal was "stupid, thoughtless, and painfully out of line with our principles", adding: "We will use the scar tissue from this painful mistake to help make better decisions going forward, ones that match our mission." Amazon says it won't delete readers' books again, while a spokesman for Sony claims in an email that "Once a customer buys a book, we don't have the ability to remove it from their Reader". Apple said nobody was available to comment.

The goodwill of digital booksellers notwithstanding, the Orwell incident exposed the new relationship we have with our possessions. The potential implications of a system in which we license books and other media from companies who have ultimate control are, in the case of the Amazon gaffe, appropriately Orwellian. "If this is the regime of the future and it requires revocation as a means of maintaining the license holders' monopoly over the work, we're setting the stage for a world in which surveillance becomes the norm," says Cory Doctorow, a technology activist, author and co-editor of BoingBoing.net. "I like Amazon – I sell my books there – but nobody is suited to be the lord high executioner of books."

In The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It, Harvard law professor Jonathan Zittrain raises the spectre of some future government censor: "Imagine a world in which all copies of once-censored books like Candide, The Call of the Wild, and Ulysses had been permanently destroyed at the time of the censoring and could not be studied or enjoyed after subsequent decision-makers lifted the ban."

One name we haven't yet mentioned is Google. Five years since Larry Page and Sergey Brin launched Google Books, the web giant has gone on to scan and upload more than 10 million titles, making them freely available as part of its bid to "organise the world's information". At the moment Google is restricted to uploading public domain and out-of-copyright works, but if their model prevails and heralds a new order in which DRM ceases to exists, ownership could become irrelevant. Can you own something if it's free and exists only in "the cloud"?

Zittrain says the law needs to catch up with the technology to prevent a scenario in which "a court-ordered change at Google could affect every participating library and consumer's version of the book". He adds in an email: "Devices like the Kindle and services like Google Books ought to be designed so that people can back up a copy of a work that places it beyond the reach of the vendor, and anyone who might order the vendor around."

Back in Detroit, Justin Gawronski has finished studying Nineteen Eighty-Four. He used a paperback copy of the book he already owned – really owned – to complete his studies and, in the meantime, sued Amazon for rendering useless the notes he had made on his Kindle. "That was the real kicker," he says. "I put a few solid weeks of work into that novel and while the notes were still there, they referred back to nothing." In the end Gawronski and Amazon reached a settlement, which was donated to charity. "I didn't want to make money or take advantage of a company," he explains, "I merely wanted to prevent such an atrocious use of DRM from happening again." And his Kindle? "It's broken," he says.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks