'Pride and Prejudice' has been reimagined as a computer game - with Elizabeth Bennet constantly on the run through the classic text

Is it a great way to introduce Jane Austen's work to non-readers, or a case of playing fast and loose with literature, asks Ryan Vogt

Recently, I broke a personal rule of mine: never quitting a book before finishing it. The novel I deserted was none other than the much-loved Pride and Prejudice. But before you choke yourselves with your chokers, know that I gave up on my first attempt at reading this novel not because I liked it too little, but because I liked it too much.

The fault, you see, lay not in the book, but its method of delivery: It was presented by a new video game, Stride & Prejudice, which is "an endless runner based on Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen", according to its tagline. This isn't your usual "based on" video-game adaptation of literature, such as the 2010 hack'n'slash inspired by Dante's Inferno, or the interactive version of The Great Gatsby (see below).

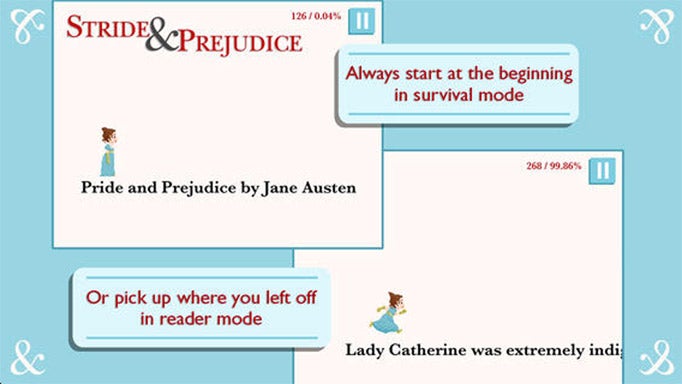

In Stride & Prejudice, the book is the game, its words forming a steady succession of platforms that your character, Elizabeth Bennet, runs and jumps across. It's a 2D sidescroller, like Mario, except that you don't have to worry about moving the character forward. Elizabeth runs on her own, so your only task is to tap the screen to jump the gaps between the strings of text rushing your way.

Stride & Prejudice offers two ways to play. Survival mode works like a typical endless runner game – that is, the goal is to see how far you can get in the book before Elizabeth falls. Survival mode is meant to be played over and over, with the challenge of beating your high score, and has the ancillary effect of drilling the book's earliest passages into your head, including its famous opening line:

It is a truth universally acknowledged,

[tap the screen, Ryan!]

that a single man in possession

[tap now!]

of a good fortune,

[jump!]

must be in want of a wife.

What keeps Stride & Prejudice from being just an, ahem, novel take on the endless runner, though, is reader mode, in which you can "die" infinite times and Elizabeth will reincarnate where she left off. In effect, it's the book, except with auto-scrolling text and the constant requirement to jump. At 69p, Stride & Prejudice is the same price as the Kindle edition of Austen's novel, except the game saves you from the bother of having to move your eyes to where the words are – what a hassle! – and moves the words to where you're looking.

Now, it's easy to give in to the kind of predictable tut-tutting that Stride & Prejudice invites at first glance. Two hundred years after this great novel was published, this is the state of pop culture? Have our minds been so fractured by multi-tasking that we get bored by entertainments that don't give us "something to do" while we're being entertained? But my main reaction to Stride & Prejudice is simply: this isn't a game. Tapping the screen while "playing" Stride & Prejudice becomes as unconscious a process as turning a page, or holding your iPhone, almost immediately.

Indeed, the true downside of consuming Pride and Prejudice in this manner isn't that you're too distracted playing the game to read the book – it's having to read at a pace other than your own. You can adjust how quickly the words scroll, but no one reads at a steady, constant speed.

The benefit, I suppose, of reading at the speed at which you can read, rather than the speed at which you would, is that you cover a lot of ground. After just a couple of hours, I had made it 37.96 per cent through the novel. As Mr Darcy tells Elizabeth, when she asks him exactly when he began to have feelings for her, "I was in the middle before I knew that I had begun." The immediate cost of this information injection is an intense visual hangover.

You get so inured to the constant flow of text that your vision continues to swim horizontally for several minutes after you stop playing the game. The longer-term cost is a lack of control over your reading experience, and an attendant reduction in retention.

If you're reading great books just to check them off your list, Stride & Prejudice might be the first entry of your favourite new video game series. On the other hand, if that describes you, I can't help but affect the snobbery of a true Janeite – you know, someone who's actually completed one of her books – and respond to you the way Elizabeth responded to one of Mr Darcy's early attempts at conversation:

"What think you of books?" said he, smiling.

"Books – Oh! no. – I am sure we never read the same, or not with the same feelings."

I asked Carla Engelbrecht Fisher, who created Stride & Prejudice, why she had made it. Was she trying to encourage people to read classics? "I'm honestly divided on making other books into endless runners," she told me. "I've joked that we could easily do Anna Ka-running-na or Frank-run-stein, but those texts are dense," whereas Pride and Prejudice is simple enough to be understood in stock-ticker form."

So is it a game or a book? "I see it as a gateway app for both book-lovers and gamers," she said. "Gamers who would never think to read Jane Austen have told me they're now reading the book, some entirely within the game."

Some. But not me. Fisher accomplished her mission, in that I plan to see where/whom Elizabeth runs to at the end of her not-endless journey (and I have a feeling I know the answer). But it won't be the pixel-art Elizabeth I see at the finish line, cute though she may be. It will be the Elizabeth whom Jane Austen and I co-create in my mind, at our own pace.

Stride & Prejudice (iOS, £0.69) is out now

Read the novel: play the game

Romance of the Three Kingdoms (series; 1985-present)

This series of strategy games based on the 14th-century Chinese novel of the same name pays homage to the complex plot of the 800,000 word epic the only way it could: by offering a game so complicated that the instruction manual rivals the source material for size.

BioShock (PC, Xbox 360, PS3; 2007)

Set in the underwater city of Rapture, this acclaimed shooter imagines a world where Ayn Rand's philosophy of objectivism as espoused in her novels has been left to run wild. When you're faced with genetically enhanced businessmen trying to rip out your eyes, government regulation suddenly seems a good idea.

American McGee's Alice (PC, Xbox 360; 2000)

If you ever thought that Lewis Carroll's Alice novels were more sinister than playful then this and its 2011 sequel offer exactly the right sort of rabbit hole. Alice is driven mad after witnessing the death of her family in a house fire and returns to a haunted and bloody Wonderland as an escape from reality.

Fahrenheit 451 (Atari, Commodore 64, PC; 1984)

Taking place five years after the events of Ray Bradbury's novel, this sequel sees former book-burner Guy Montag evading capture and trying to meet up with the reading underground. The game's most testing moments demand that players cough up literary quotations.

The Great Gatsby Game (online; 2013)

This 8-bit platformer has players take control of Nick Carraway as he navigates his way around Gatsby's mansion, dodging martini-toting butlers and collecting shiny gold coins.

JAMES VINCENT

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks