How I rescued my brain: Psychologist David Roland rewired his thoughts following a stroke

The forensic psychologist David Roland was burdened by the traumatic nature of his work and facing financial ruin. When he woke up in A&E, with little idea how he got there, it was thought he'd had a breakdown. But in time the doctors worked out that he'd suffered a stroke. In this exclusive extract from his new book, he describes the aftermath

I'm having trouble working out where I am. Somehow, this isn't perturbing, simply puzzling to me. I'm in a puzzle and need to put together the clues to work out what this is all about.

I'm sitting in the centre of a row of beige plastic chairs. When I turn my head, I realise that my wife, Anna, is next to me. A ring of beige chairs also lines the walls. Other people, scattered around the room, are flicking through magazines or looking down and shuffling their feet. I get the feeling that they don't want to be here.

A beeping sound is coming from somewhere. To my right, people are moving through an automatic door, which shudders as it opens. I look up to see a woman behind a counter and a glass window. She seems harassed, and her dark hair hasn't been brushed recently. She's on the phone and taking notes. Every so often, people go up to the opening in the window and talk to her. She frowns when they approach, as though she doesn't really want to speak to them.

We seem to be in some sort of waiting room, but I don't know why.

I look around. There are posters on the walls with bold letters reading, "Cover Your Cough", "For Infection Control Reasons, Wash Your Hands" and other things. Lots of the posters have people on them looking pleased or sad.

The sunlight slanting through the windows on the far wall is soft; it must be the morning light, then.

In one corner of the room, on a low table, there are piles of magazines. I walk over to pick up Country Life and then sit down again. There's a section about property, with pictures of quaint, homely looking cottages; some have picket fences. Other photographs show mansions, built of sandstone or solid-looking bricks. When I look at the date on the cover, 2007, I realise that I don't know what year it is now [David had his stroke in August 2009].

Off to my left, a child is whining. I turn to see a man and a woman, both big, with a girl aged four or five. They look tired, as parents do when they've been up during the night with a grumpy child. Soon I am absorbed by their interactions; it's like watching a show. The father lifts the girl on to his lap, looking strained. The mother holds up a children's book, reading to her. The child listens for a while, fidgets, and cries again. The mother tries to interest her in one of the toys from a box in the corner, but it doesn't work. I know what this is like; I'm a parent, too. They're doing their best.

How did I get to this room? A fragment comes into my mind – a dreamlike image – of Anna driving us and me vomiting out of the car window. Did this really happen, or am I imagining it?

I turn to Anna and see that she's crying quietly: her cheeks are pink; the rims of her eyes are red. She's sad about something, but I don't know what. I put my arm around her shoulder and pat her gently. "It'll be all right," I say. She quiets a little.

As we sit there, I feel as if I'm in a sound bubble, into which the surrounding noises don't intrude. The crying girl doesn't irritate me as I think she might have at another time. Instead, I feel a well of stillness inside. I keep turning the pages of Country Life.

As far as I can tell, it's not long before we are taken through a door. It opens, like magic, into a wide, yellow corridor with a side table, a high metal chair, and shelves along the walls.

A young man who says he is a doctor asks me to sit in the chair while he stands before me. He's wearing ordinary clothes and looks tired, speaking slowly and softly. He probably wants to go home. The doctor would like to know the day of the week. I'd like to oblige, and think hard. It's Wednesday, or it could be Thursday, I say.

I don't know how long I'm with the doctor – perhaps one or two minutes – and when I look up he's gone. There's that puzzling feeling again: was he real, or am I in a dream?

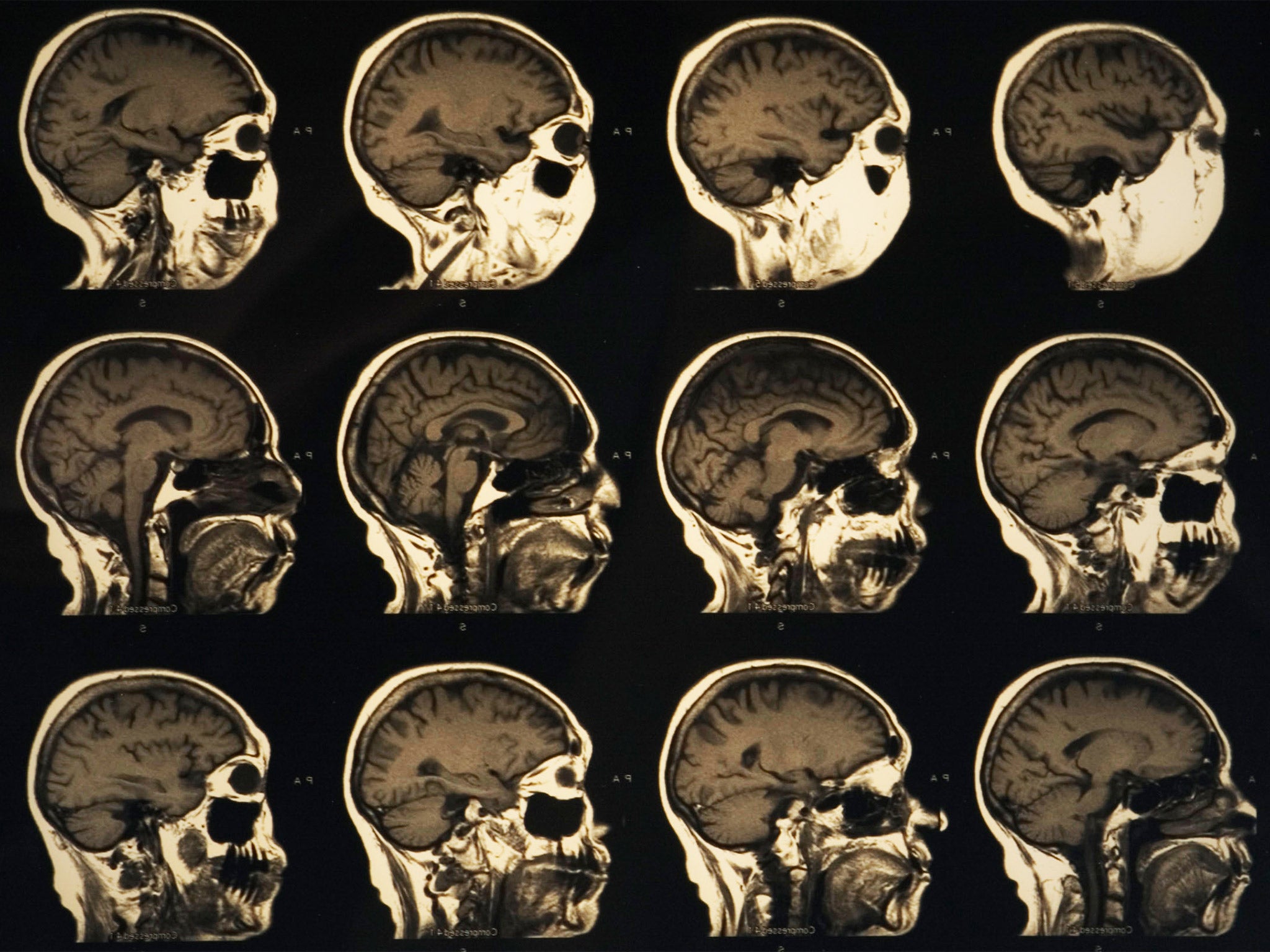

Back in the corridor, a man and a woman tell me I am to have a CT scan. The thought excites me. I don't think I've ever had one before, but I know what they are: I've read reports from CT scans in client files, detailing the effects of a brain injury or disease. They have a wheelchair and push me into another corridor. In and out of lifts we go. It is fun.

Now we're entering a room with a giant shiny doughnut, and a sliding platform that goes into it. My head will go into the doughnut, they say. Before I know it, I'm being pushed away from the CT room – they say the scan is over, but I don't remember having it. How odd!

I'm walking with a woman, also dressed in blue; she's told me that I'm staying in a ward tonight. I'm not sure if I've stayed in hospital before, but I'm so tired that I think it would be great to spend the night here.

The next morning is different from the day before. It feels as if I've woken from a dream. I'm sure now that I'm in hospital, and that something really has happened to me. I remember more clearly the night before I came in. I'd woken with a headache, walked to the kitchen, taken a Panadol, and gone back to bed. That's the last memory I have before being here.

The phone beside my bed rings, interrupting my reverie. It's my psychiatrist, Dr Banister. Anna has called him, he says.

"What's happened?" he asks.

I tell him that I can't recall most of yesterday.

"What do you think brought this on?"

I remember I'd had a huge panic attack the day before I came to hospital. Dr Banister asks me what tests have been done.

"You may have had a psychogenic fugue: an episode of amnesia. But we'll need to wait and see what the results reveal. I'll try and come in to see you. If it's a fugue, you could come and stay at a clinic I work for, Seaview Psychiatric Clinic, for a longer rest. I can discuss this with your doctor."

Not long afterwards, the specialist comes in and stands by my bed. He looks fresh now, but more rushed than yesterday. He asks me how I'm feeling.

"I'm woolly in the head, as if I'm not sure I'm really here," I reply to him. "I've got a mild headache, too."

He says that the tests came back negative, my heart is fine, and the CT scan did not show any problems with my brain. Thinking it might be useful, I tell him that my psychiatrist rang and thought I might have had a psychogenic fugue. He looks relieved to hear this suggestion. He wants me to stay for another night so that they can monitor me, and after this, if he's satisfied, I can go to Seaview, as long as Anna takes me.

It's three weeks after my initial hospital admission, and two weeks after I was formally discharged from Seaview, where I spent eight unsettling and confining days. It's mid-afternoon and I'm reading Elizabeth Gilbert's Eat, Pray, Love. It's easy to follow, and it doesn't matter if I've forgotten some of the earlier details. I like her writing, and am buoyed by her story: I'm not the only one on a path of survival. Initially I tried reading Synaptic Self by Joseph LeDoux, a neuroscientist, but it was like trudging through thick, deep mud.

I would read a page, and by the time I reached the next, I'd forgotten what the previous one had said. My phone rings. It's the doctor from the hospital. "I'm sorry," he says, "but I've got some unfortunate news. We made a mistake. The result of the brain MRI you completed yesterday shows that you've had a stroke."

"Oh."

"I'm sorry it wasn't picked up earlier," he says. "It's affected the occipital region – the vision area of your brain – with some minor bleeding in other parts. Have you noticed any disturbances in your visual field?"

"I don't think so," I say. I sense the gravity in his voice, and feel I should respond to it. "What do I do now?"

"Well, it's been three weeks since the stroke happened. If something else were going to occur, it most likely would have by now. But you should see your GP straight away. Get some advice."

"OK," I say, and we finish the call.

A stroke. Fancy that.

I go back to reading, settling comfortably into my chair; the idea of seeing the GP slips into my back pocket. But my brain continues processing this information in its own way.

After a while, a niggling thought presses in on me: Perhaps I should see my GP now, or at least make an appointment? The hospital doctor did sound serious.

So I fold up the chair, gather my things, and amble off to the car. As I drive down the potholed road back to town, the word "stroke" rolls around in my mind. It doesn't take on any particular shape, but I know that it's a physical condition, something with medical implications, although I can't think of what they are.

Then, a thought comes suddenly to my mind: if I've had a stroke, and that's physical… I haven't had a mental breakdown. Relief floods through me. Fucking fantastic.

But cue seven months of visits to doctors and a series of tests. I now take a small dose of aspirin daily. I've been told that I should rest rather than exercise, walk on flat ground if I go for a walk (no inclines), read nothing harder than the newspaper (I should be fine with Eat, Pray, Love). I try to follow doctor's orders to take it easy and avoid stress. The stroke thing is a process of discovery. The invisible hole in my head is a trickster; I don't know when or how it's going to trip me up next. My body's not behaving properly either.

I'm anxious to get on with my recovery, and the more I read, the more it seems like a computer-based cognitive training program is what I need. But what program do I use? An internet search reveals that there are few commercially available programs, and what little scientific research I can find points to Posit Science having the most backing for its claims.

When I look at the Posit Science website, it offers two programs designed to help the elderly with the common outcomes of cognitive decline associated with ageing. The InSight program improves visual processing. The Brain Fitness program improves auditory processing: forgetting names, slowness of thinking, difficulty in word retrieval, difficulty in deciphering speech and fatigue in conversation. I'm not elderly, but this describes me perfectly.

The program concentrates on building the basic auditory skills first (pitch and phonemes), and then the components of speech (syllables and sentences) and finally comprehension (narratives). It contains six different exercises, which I work through progressively.

As I get into the rhythm of the program, most days I advance on an exercise or stay at the same level. But sometimes I have an off day. That's when I see, in the form of the progress bar, how dramatically my performance drops off when I'm mentally or physically fatigued – the clearest indication so far that fatigue really does affect my day-to-day capacity to function.

After one month of doing 30 minutes most days, I have progressed up the ladder to some degree in all exercises. But I haven't noticed a great difference in my auditory processing outside these exercises. I'm a little discouraged by this. Yet the cheerful male voice that explains what each exercise does and why it is useful shows a picture of the brain with coloured lines connecting the areas that each exercise works on, reassuring me that I am making new neural connections. If it doesn't work, I've only wasted some time and some money.

In late November 2010, 16 months after my stroke, I awake early one morning with rubber brain, a feeling that usually occurs when I've been concentrating too long: the conversation has gone on for more than 30 minutes, or the noises around me have sucked my mental energy dry, or I'm speaking to a new person who wants to know all the details of my story. With rubber brain, when someone speaks to me, I have the sensation of his or her words bouncing off my brain: nothing comes in and nothing goes out.

I get up and meditate anyway. As I try to focus on my breath, the home phone keeps ringing, but my daughters don't answer it. Who's calling, and why won't someone pick up the phone to make the noise stop?

Later, after breakfast, I feel rushed and unsettled as I make the school lunches in the kitchen. Anna has already left, so I will be getting the girls off to school on my own. The dread is with me, and it intensifies by the minute. I butter crackers, but each one I pick up breaks, my hands are shaking so much.

I can't do this. I can't cope any more.

I throw my favourite cereal bowl into the sink, followed by my tea mug. The loud crash it makes is oddly exhilarating. I pick up the plastic box holding the cartons of crackers and propel it into the pantry door, as if throwing a football. The jar of Vegemite follows. A cascade of foodstuffs clatters off the shelves.

I've been trying to hold everything together, but as the year has gone on, my reservoir of fatigue has risen like floodwaters. I phone Anna in desperation. "I can't cope any more. You'd better come home now." She tells me that she'd been the one ringing earlier.

I drive my daughter to the bus stop because she is running late again. The two younger ones are nowhere to be seen – but when I come back, I find them in the kitchen, picking through the debris and commenting like disaster experts on the turn of events. The pantry floor is frothing with fallen boxes and jars, and crumbs from the broken crackers dot the ground like confetti. My breakfast cereal bowl lies in fragments in the sink.

The next day, Anna tells me that she needs to talk. Hesitantly, she says she may be suffering from compassion fatigue over my condition. I tell her that I am not coping with the normal daily demands along with my rehabilitation commitments. Yesterday's incident has shown me I must change something, that I need a rest. Anna thinks it would be good for me to go away for a time, so we can all have a break. And I have an idea.

In the middle of last year, there was a call-out in our community for billets for people attending a seminar given by a visiting international Buddhist teacher. When I picked up our assigned billet from the bus station, she turned out to be a Tibetan Buddhist nun, Choeying. Over the course of the nine days that Choeying stayed with us, Anna and I each talked to her. I quickly sensed that I could trust her and could speak frankly. At the end of her stay, Choeying invited us to visit her, and January 2011 seemed like the perfect time to take her up on it.

"We have to look at our minds," she tells me, as we prepare to meditate. "Our senses create desire in us. We like chocolate, but we can't just have one piece because desire takes over and then we guzzle and feel sick and wish we hadn't. But the next time we have chocolate, we have too much again. We like a particular type of music, so we listen to it over and over until it becomes dull. What we look at, feel, taste, touch and smell is neither good nor bad. If we perceive it as good, we can't get enough. If it's bad, we can't get away fast enough. On the other hand, if we see everything as 'just is', we see a new reality."

Several days into my stay, I have the following conversation with Choeying. "I've been thinking about what you've been saying about what happens with meditation," I say. "I think I experienced these things when I had the stroke."

I describe what it was like being in the waiting room at the hospital and during the investigations with the doctors. How I wasn't really perturbed by anything. How everything and everyone seemed fascinating, and I didn't have a sense of people being good or bad, inferior or superior, and wasn't troubled by thoughts of whether I liked them or not. Time became irrelevant. I felt present in each moment as it unfolded, thinking neither about the past nor about the future.

"It's remarkable. Your experience... meditators take years to achieve these things. I've been sitting on my bum for years, looking at my crazy mind to experience something as profound as you have. Wow. A knock on the head: it's a fast track to enlightenment!" Choeying says. We both laugh.

It sounds preposterous, but I think there's some truth to it. I've only seen my stroke as something bad that has happened to me, as something gone wrong, but now I can see it as something special.

'How I Rescued My Brain: A Psychologist's Remarkable Recovery from Stroke and Trauma' by David Roland (Scribe) is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments