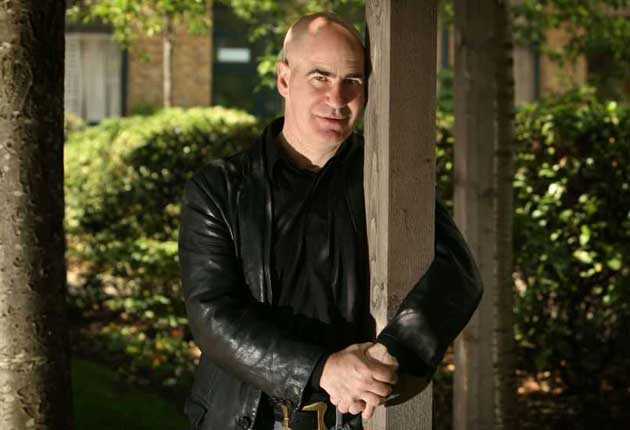

Jonathan Hartman: Saying goodbye to my father

He was irascible, bloody-minded and as a father, less than adequate. Now he was dying. So how exactly should his only son Jonathan Hartman say farewell?

The news of my elderly father's terminal cancer was broken by the family physician, a brisk Hungarian who'd survived Auschwitz and whose bedside manner owed a certain debt to that of the late Dr Mengele. "Absolutely no hope," he told me, breezily. "When we put him in the CAT scanner, he lit up like a Christmas tree."

I expressed mild dismay. "Well," he commiserated, "at 22, it would be a tragedy. At 77, it's simply what you die from. And anyway, he's such a nasty old man ... "

The doctor had a point. As Jean de la Fontaine said in 1688, "It is impossible to please the entire world, and one's father," and to this day I do not know whether my father's last words to me, his sole offspring, were "Goo'bye" or "Go'way". Either were possible. He was an odd man, to say the least, one who would march to the beat of a different drummer, and then loudly and abusively tell the drummer to shut up. In the years since his death, there has been no catharsis, just a lingering and regrettable feeling of relief.

It had been quick and unexpected. My elderly maiden aunt, his older sister, with whom he lived, had summoned me because he was feeling ill. "I'm going into hospital," he announced calmly. "My will's in the top drawer," and he received the diagnosis with a laconic "Fuck it. 77's old enough. No more tests. No treatment. I'm cashing in my chips."

Knowing I was contracted to act in a Shakespeare play in the near future, he told me to get on with that whatever happened to him. I smiled and with the gallows humour we shared, told him it would be more convenient if he'd die before I started rehearsals, or hold off until the run ended. He chuckled grimly and said he'd work on it.

A difficult patient, he fearlessly faced eternity by ensuring he did not expire with any venom left unused, and took great delight in inflicting his personality on the other unfortunate denizens of his ward like a latter-day suburban Caligula engineering a sanguine hit-and-run. "Is that your father?" the woman visiting the adjacent patient asked me – and without waiting for an answer, demanded in astonished exasperation: "What kind of woman would marry a man like that?!"

My mere presence indicated that the unbelievable had indeed transpired, but I honestly couldn't think of a rejoinder. I was too busy recalling The Unpleasantness of the Lemon Pie. Certain memories tend to brand themselves onto the frontal lobes, and a strange horror still overcomes me when I look at a lemon meringue.

That mother had a martyrdom complex to rival Joan of Arc's was indisputable. And the carpet did need cleaning. But to rent a steam cleaner, to transport it home, to move all the furniture herself while loudly refusing any offers of aid, to attempt the resurrection of a carpet that should have been retired years previously, and above all, afterwards, at the dinner table, to inform my father and eight-year-old self repeatedly and with great passion that should so much as the smallest crumb mar her efforts ...

Father had had enough. With a dignity and deliberation that bordered on the ceremonial, he lifted an entire pie plate of lemon meringue over the carpet, and inverted it. Expressionless in the sepulchral hush that followed, he stepped into the detritus, whooped, and executed a few steps in an inspired imitation of James Brown – in retrospect, a superb tribute, even considering his dual handicap of late middle age and Caucasianhood. Mother's reaction would have fascinated and inspired a legion of Berserkers. So traumatic was what followed that I honestly remember nothing of it – but this was yet another very typical chapter of a childhood spent trapped in a squash court, frantically attempting to dodge two ricocheting balls of antimatter.

My two pet turtles were a grain of consolation, a rare gift from my father who solemnly informed me their names were Leopold and Loeb. It was years before I figured that one out. (They were homosexual lovers who committed a carefully planned, completely recreational murder in 1924.)

As the old saying goes: "When a father helps a son, both laugh, and when a son helps a father, both cry." But it wasn't like that with us – day after day I sat by his bedside in hospital as his illness progressed, trying to keep him company, and whenever I tried to make conversation or express sympathy for his plight, he just snarled at me. I knew he was feeling slightly better once when he called me a prick and criticised my jacket. Finally I decided I'd had enough. And I resolved to confront him whether he was dying or not, to ask about all the rages, the insults, the unacknowledged birthdays, the broken promises and the vague feeling that my existence had always been something of an unwelcome surprise for him, born unexpectedly as I was in his mid-forties. Head held high, with the unshakeable determination of someone who'd made an irrevocable decision, I marched into his ward, approached his bed, fixed him with a steely glare ... and he looked up at me and smiled.

I'd never before realised how blue his eyes were. "This is a nice hotel," he said. "However did you find me? And where's your room?" He glanced from side to side, and then, with a soft, conspiratorial expression, confided, "I have to stay here until we find why I'm so lethargic. Does your mother know I'm sick?" I conveyed her best wishes for his recovery, deeming this more discreet than reminding him she'd already been dead for eight years. There was a very pleasant old gentleman lying there, and it certainly wasn't my father any more. I knew then that there would never be any answers or revelations, and that all I could do now was sit, watch, and wait.

He began to sleep more and more, slipping away, and though he could not hear me I thanked him for the good times – for coping reasonably well with an energetic boy born to him in middle age, teaching me to ride my bicycle, to throw a ball, for making me a paper airplane once even though I'd woken him from a nap to do it, for instilling a love for Groucho Marx and Shakespeare, for coaching me through a recitation of The Shooting of Dan McGrew, for teaching me to regard politicians and the sanctimoniously religious with suspicion, and ensuring I knew iconoclasm is not necessarily a bad thing – breathes ever man with soul so dead/who was not in the Thirties, Red?

However, the problem with deathbeds is that they aren't only depressing; they can be pretty boring as well. Sometimes you wish the dear (pre) deceased would get on with it – but he rallied, once. A doctor dropped by to check his mental condition, and the old man, pathetically eager to please, made him welcome. "Do you know what day it is?" the doctor asked. Father looked troubled, confused. "Well, do you know what month, what year? Who is the Prime Minister?" It was as if Father was trying desperately to hold onto handfuls of sand, and his puzzlement was both pathetic and palpable. "Does it bother you that you don't know?" asked the doctor, gently.

And for one final time the old man gathered the remnants of his essence, and his eyes recovered their mockingly malignant glare. "No," he said, firmly. "In fact, I don't give a fuck." Then he sighed, smiled at us pleasantly, and I knew the last of him had faded forever.

I knew very little about my father's boyhood, never having had grandparents to tell me secrets. But one day as I sat next to him while he lay comatose in his oxygen tent, Sam, an aged relative, paid a visit. He told me how, as a child, he'd pulled his wagon on a five-mile journey to visit my father, and had made him a toy car by pulling some boards off the back alley fence, and nailing them to it. "Then I left him to play with the thing, and had to walk all the way home because I didn't have the wagon to push myself along in, or five cents for the tram. I was 12, and he was seven." He regarded the dying man and smiled bleakly. "And it's been 70 years, and he hasn't thanked me yet."

Shortly thereafter the doctor told me he'd probably die in about two days, and I sat with him for most of that time, watching the breathing fade and restart, and watching the face sink in and yellow, which served to accentuate the purplish circles growing around his eyes. Towards nightfall on the last day his respiration eased, the dreadful groaning he made as he tried to draw breath smoothing out a bit, and he opened his eyes. We looked at one another, and I told him gently it had gone on long enough, that it was time, and to let himself slip away. I took his hand. As a child, his nightly farewell to me had been, "Goodnight, sweet prince, and flights of angels sing thee to thy rest."

"Fear no more the heat of the sun," I began, "nor the furious winter's rages/Thou thy worldly task has done/Home art gone, and ta'en thy wages ... "

"Go'way," he murmured. Or maybe it was "goo'bye". I'll never know. I kissed his forehead – it was burning with fever – and walked out. He died that night.

He left me his cynicism, his piercing stare, his love for cats, a deep baritone voice, and an enchantingly bitter sense of humour, which I'm flattered to be told I've inherited. Well, it's more enduring and certainly more valuable than the estate he bequeathed me. Freed by divorce and retirement from the strictures of family life, my father was able to focus his undivided attention on horse racing. His enthusiasm for the "sport of kings" was only equalled by his ineptitude at betting. One could call him an extremely handicapped handicapper.

Inscriptions on tombstones bother me. "Sadly Missed", "Dearly Beloved", "Ever In Our Thoughts" – do only good people die? Is not a single one of the "bereaved" ambivalent? I chose black granite for his stone, and a few lines from Shakespeare: "The web of our life is of a mingled yarn, good and ill together. Our virtues would be proud if our faults whipped them not, and our crimes would despair if they were not cherished by our virtues."

And above his name and the dates is crosshatched the head of a hooded racehorse at full gallop, mane flying, and straining at the bit. The stonecutter did a beautiful job. He even managed to capture the slightly desperate expression a horse wears when it's running last.

Bye, Dad. Happy Father's Day.

Jonathan Hartman trained at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School, and has acted on stage, film, TV and radio for over 20 years in England, Europe and North America. His next ambition is to join MI5, having perfected the art of working for years in the public eye while still managing to maintain an almost terminal anonymity. Jonathan's showreel is viewable on YouTube. jonmath@hotmail.com

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies