Rehab needs a fix

Mitch Winehouse's plan to open a rehab centre in memory of his daughter has shone a spotlight on the scandalous state of treatment for young addicts in Britain. Nina Lakhani reports

When a bereaved father made a public plea for more rehab clinics this week, he was probably unaware of the war of words that has engulfed the addictions debate over the past 10 years.

Mitch Winehouse plans to set up a rehab centre for young people in memory of his daughter, who died last month after a long, ugly and heart-wrenching fight with addiction. Meeting with MPs on Monday, he explained that "this isn't about Amy because we were in a fortunate position of being able to fund Amy to go into private rehab – this is about people that can't afford it".

Amy's Rehab could, her father hopes, become a lifeline for young addicts. Britain's only specialist residential rehab for young people, Middlegate in Nettleton, Lincolnshire, closed down in 2010 after 15 years. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the closure of the five-bed clinic attracted less media outrage than pictures of intoxicated youngsters, which routinely trigger breakfast television debates.

But it is far more serious than one lost clinic. The closure of Middlegate was part of a trend which has seen the decimation of Britain's residential rehab clinics. Approximately a quarter of clinics shut down because of "insufficient referrals" between 2008 and 2010, leaving less than 1,900 beds across the country. There are no NHS-run clinics, only those favoured by celebrities such as The Priory or small not-for-profit clinics such as Western Counselling and The Ley Community.

Even so, many are struggling to keep their heads above water. Yesterday, around half off all rehab beds lay empty as NHS trusts, drug agencies, social services and the police seem increasingly reluctant to send addicts for treatment regarded as too expensive.

The closures, empty beds and apparent lack of need for residential rehab have occurred despite an estimated 330,000 problem drug users in England who cost society more than £15 billion a year in drug-related crime, benefits and health services.

This doesn't mean governments have been scrimping on drug services, far from it. In 2009, £1.2bn was spent trying to tackle heroin and crack cocaine use, widely regarded as the most dangerous and costly to society.

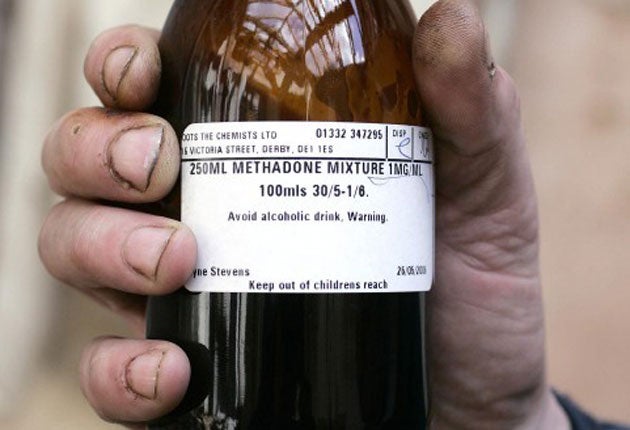

But under the last government, residential rehab became a service non grata. Instead, the National Treatment Agency spends more than £700m on community services which, by and large, involves addicts receiving methadone prescriptions to help stay off heroin, and fortnightly meetings with a drug worker. A staggering 2.5 million methadone prescriptions were handed out in England last year in the hope that it would cut drug-related crime and help bring stability to chaotic lives.

The speed at which the NTA publicly dismissed Mitch Winehouse's claim that addicts often wait more than two years for treatment perhaps demonstrates how polarised and personal the addictions world has become. Paul Hayes, NTA chief executive, insists that more than 90 per cent of addicts in England wait less than three weeks for treatment. "The popular image of a spell in a luxury rehab, beloved of celebrities and the tabloids, is not representative of the mainstream treatment and recovery services provided in this country by both the NHS and the voluntary sector," he said.

To Hayes and the NTA, treatment includes all those people who have been assessed by a drug service and offered a follow-up appointment. The NTA says 168,000 people were in "effective treatment" last year and 28,000 of those "left treatment satisfactorily".

But official figures suggest only 4 per cent of addicts emerge from treatment free from dependency. The problem, to some extent, is one of words and priorities. For the NTA, a satisfactory treatment could mean the person has stopped using one drug but continues to use others. Deirdre Boyd, chief executive of the Alcohol Recovery Foundation, says: "This is the equivalent of saying that an alcoholic has successfully completed treatment because he is free of whiskey but is now dependent on vodka."

She and others in the rehab world tell desperate story after desperate story of addicts refused residential rehab even though they are desperate to come off drugs and cannot do it in the community. The majority of heroin addicts are kept on long-term maintenance methadone when three-quarters actually want to become drug free, according to the Drug Outcome Research in Scotland project.

Professor Neil McKeganey, director of the Centre for Drug Misuse Research in Glasgow, said addicts and their families had been let down by the NTA's refusal to support residential rehab services. "If you are lucky or wealthy enough to get a period of treatment in rehab in Britain, you are some seven times more likely to become drug-free than an individual in a methadone community project. The evidence is sound and unambiguous but the NTA's refusal to support the rehab sector has led to dwindling numbers."

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence makes recommendations about which treatments are cost-effective for the NHS to use in England. In 2007 it said that residential rehab should only be provided to drug users after every community option had been exhausted.

This has led to far more damaged and desperate people by the time they eventually get to rehab, according to Amanda Thomas, director of the Western Counselling recovery programme.

"We have seen a massive change. People are far more damaged and entrenched in their addictions by the time they get to us. Rarely do we get someone who isn't on anti-depressants, has stomach problems and have lost their housing and their families. I can understand budget pressures but it would save so much money in the long term if people came earlier. Some areas are better than others, some will refer people but some just don't fund it at all."

While celebrities may pay thousands a week for a stint in rehab, charities charge as little as £500 a week. But this is obviously unaffordable for the vast majority of individuals and families who could benefit from intensive rehabilitation. This makes addiction perhaps the most inequitable part of the health service, with proven treatments accessible only to those who can afford it.

Sarah Graham, an addictions therapist who is also a recovering alcohol and cocaine addict, says rehab saved her life 10 years ago, but only because she had the money to pay for it. She accompanied Mitch Winehouse to Parliament. She said: "If you're a young person, there is nowhere for you to go in this country. I refer them to clinics in America and South Africa, but obviously only if their parents could afford it. This is a complex, killer illness, and effective treatments should be available to everyone."

Thomas said: "There are enough rehab places in the country, they just need to be utilised for people when they need them. We hear of people dying all the time who are on our lists, who apparently hadn't demonstrated that they were ready or worthy enough, and this is tragic. If people were dying waiting to get treatment for any other condition it would be a national scandal, but the discrimination against addiction means that it's okay for them."

Coroners recorded 2,182 drug-related deaths in the UK in 2009 – a 12 per cent increase on the previous year.

The Tory party was incredibly vocal about its disdain for Labour's love of methadone and promised to increase access to abstinence-based programmes, such as residential rehab. Its eight Drug Recovery pilot projects, which start in October, will pay services by result, rewarding specific-outcomes crime reduction, improvements in health, and addicts getting into jobs. But abstinence, or being drug-free, is not an outcome worthy of payment and rehab clinics are not allowed to participate in the pilots. This has turned widespread hope into widespread disappointment, amid accusations that the Coalition is falling into well-oiled traps.

Professor McKeganey says: "I was encouraged by Government at first but to be honest it has lost its nerve. They are receiving advice from the same senior civil servants as the last government which means they are unlikely to deliver their promise of change."

Amy Winehouse's family await the results of toxicology tests to establish the cause of her death. Her father says that she stopped hard drugs three years ago, but had been unable to stop drinking alcohol. The singer won three Grammy awards for her song "Rehab", which described her refusal to enter a drug rehabilitation clinic.

Her father seems to have the ear of several high-profile MPs and is on a mission to make something good come out of Amy's death, and give at least some young people, and their families, the option of rehab regardless of wealth.

The addict's tale

Keith Vicarage, 53, from north London, entered residential rehab after 35 years of addiction to hard drugs including heroin and crack cocaine. In the end, comedian Russell Brand helped him to get into Focus 12 after hearing his desperation at a Narcotics Anonymous meeting just before Christmas 2009.

"Drugs allowed me to cushion all my problems and heroin was the universal painkiller. My life as an addict was one of constant desperation, always a fear and anxiety that I would go into withdrawal. I spent 15 years on methadone, but like many people still took drugs on top. Now that I am clean, I realise my whole life has passed me by; I am an old guy. I try and stay thankful for being alive, because there are many others like me who are aren't. Yes I wish there had been more one-to-one work, maybe I would have gone to rehab sooner, but the best support in the world comes to very little until you have reached that point when you can no longer live with the addiction."

The private approach

Promis

The Promis Rehabilitation clinic in Kent offers a combined range of treatments, which are honed into an individualised programme. Medical attention, psychological care and guidance along with secondary care and detox are available. For young people and families, dedicated programmes are available. There's no shortage of recreational activities: the rehabilitation centre boasts a pool, table tennis, art facilities and a gym.

Affinity Lodge

With its "Body Mind Spirit" mantra, the Affinity Lodge in Great Malvern, Worcestershire, promises to "encompass the individual's physiological, psycho-emotional and spiritual needs". The addiction programme includes group and individual therapy, as well as a choice of "interventions" ranging from Satori Vibro Acoustic Therapy to Jin Shin Jyutsu Acupressure, Sogno Massage and Bright Light Therapy. The Lodge's programmes vary in longevity from three-day "intensive" stay, to its recommended four-week recovery plan.

Bayberry Clinic

Oxfordshire's Bayberry Clinic utilises the so-called Therapeutic Community approach to addictions and mental health problems. Approaching the problem as "a disorder of the whole person, which affects the physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being of the individual and the family" patients and their families are taken through a series of psycho-educational and psychotherapeutic groups. The residence attempts to recreate the environment of a family home, to "heal isolation, loneliness and behavioural problems".

The Priory

With 17 acute hospitals and clinics across England and Scotland, The Priory offers outpatient, inpatient and day-patient treatment programmes for adults, children and those detained under the 1983 Mental Health Act. It tailors programmes to suit the individual and offer a wide range of therapies including cognitive behavioural therapy and dialetic behavioural therapy. It has a history of treating celebrities.

Narconon

Narconon's residential drug rehabilitation centre is located in St Leonards-on-Sea, near Hastings. A key difference between its programme and some other drug rehabs is that Narconon does not substitute the use of one drug with another. Because users often have a depletion of vitamins and minerals, its experts recommend natural nutrition to assist the body's repair, including providing patients with a "drug bomb", a specially blended formula of certain vitamins.

By Alice-Azania Jarvis and Gillian Orr

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks