Secrets of the brain: The grey matter that makes us who we are

From shyness and moral judgement to creativity and sexual preference, a fascinating new book shows how our personalities and human traits are written on our brains. Jeremy Laurance reports

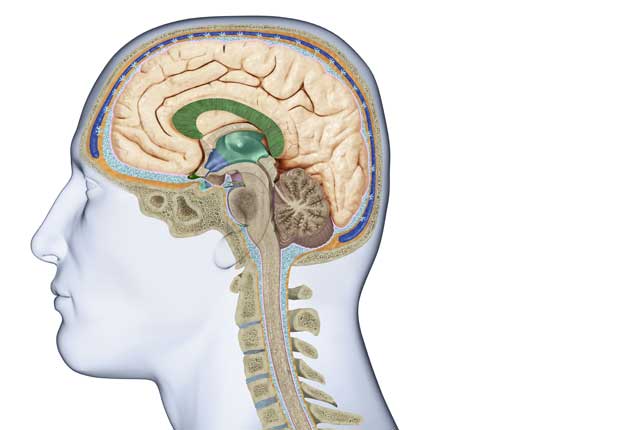

The brain is our most complex but least understood organ. We can name its parts but our knowledge of what each part does, or how, is rudimentary. In The Brain Book, journalist Rita Carter has assembled what is known about the nerve centre of each individual and explains with the aid of images and graphics its structure, function and disorders.

The moral brain

When rail worker Phineas Gage blew a hole in the front of his brain while tampering with explosives in 1848, he provided one of the earliest insights into how the organ worked. The explosion drove a rod through his cheek and out through the top of his head, causing him to lose the sight of his left eye but, remarkably, little other damage. However, his personality changed dramatically and from being a conscientious, polite and thoughtful man, he became rude, reckless and socially irresponsible. Damage to several areas of the brain involved in feeling and thinking can affect moral judgement.

Belief and superstition

A complex interplay of genes, culture and upbringing contribute to people's belief systems, which provide a framework for their experience. But certain aspects may directly reflect brain activity. Some scientists have suggested that supernatural experiences may be the result of disturbances in the brain.

The feelings of ecstasy that accompany them have been attributed to tiny seizures in the temporal lobes. Temporal lobe disturbance has also been associated with the sense of an invisible presence that people who claim to have seen ghosts often report. Out-of-the-body experiences have been linked to reduced activity in the parietal lobes, which normally maintain a stable sense of space and time.

Creativity

There is a striking difference in the brains of musicians who play from a score in front of them and those who improvise. Brain imaging studies have shown that the frontal lobes are activated when musicians are reading the notes but turn off in improvisation, allowing ideas to "float".

Research suggests that this reflects wider creative processes. When the brain relaxes out of sharp attentiveness, shown by tightly-compressed gamma waves on the EEG, into its "idling" mode, marked by slow alpha waves, that is when new ideas tend to occur. Stimuli that might otherwise be ignored are allowed to enter awareness and can resonate with thoughts, memories and existing knowledge.

Sex differences

Brains are as individual to people as faces. But there are broad differences between the sexes, and between differing sexual orientations. The corpus callosum, which links the two sides of the brain, is better developed in women than men. It has been suggested this is why women are more emotionally aware – the right side associated with the emotions is better linked to the left side, the seat of analytical thought.

Brain scans of gay people show structures associated with mood, emotion, anxiety and aggression tend to resemble those in the opposite sex. In gay women, for example, the right side of the brain tends to be larger, a feature shared with heterosexual men. Patterns are similar between gay men and heterosexual women, especially in areas involved with anxiety.

Personality

Studies of the brain have raised the possibility that personality may be "visible" from the activity in different brain areas.

At the crudest level, a person with a "sensitive" brain – one that produces more activity in response to a mild stimulus – are less likely to indulge in sensation-seeking or adrenaline sports than those with "insensitive" brains, who need a lot of stimulation to produce the same level of excitement. Extroverts have reduced activity in response to stimuli in the neural circuit that keeps the brain aroused – involving the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex and the thalamus.

People who like novelty have strong links between the hippocampus and the striatum, while shy people show a strong reaction to unfriendly-looking faces in the amygdala. Optimism, co-operation and aggression can be traced to activity-specific brain areas.

Does size matter?

Brains tend to vary little in size, but there are exceptions. Jonathan Swift, the author of Gulliver's Travels, had a brain which weighed an enormous 2,000 grams when he died in 1754, while the brain of Ivan Pavlov, the Russian physiologist who discovered the Pavlovian response, weighed barely 1,500 grams. There is no link between size of brain and intellect but other features may be important.

Einstein's brain, removed after his death, was missing part of a groove that runs through the parietal lobe. The area affected is concerned with mathematics and spatial reasoning and it is thought the missing groove may have allowed neurons in that area to communicate more easily. If so, it could account for his extraordinary talent.

The ageing brain

Most neurons in the brain remain healthy until death. But the brain itself shrinks by 5-10 per cent between the ages of 20 and 90. Other changes include a widening of the grooves and the formation of plaques and tangles – small disc-shaped growths. The significance of these changes is not understood – they may occur in the brains of healthy people and those with Alzheimer's disease.

However myelin decay, affecting the myelin sheath that insulates the neurons, increases with age and can mean brain circuits are less efficient, causing problems with balance and memory. However, decay in the physical brain may be compensated for by the accumulation of knowledge and experience, resulting in improved intellectual performance. Exercise, a healthy diet and engaging in mental tasks such as chess or crossword puzzles can slow mental decline and protect against memory loss.

Headache and migraine

A headache is the commonest reason for taking painkillers – yet the brain has no pain-sensitive nerve receptors. Tension in the meninges – the membranes that surround the brain – or in the blood vessels or muscles of the head and neck may account for some headaches. In others, such as migraines, the pain may be due to a surge of neuronal activity. Migraines usually occur at the front or side of the head and the pain often gets worse with movement. They have a range of triggers – specific foods, tiredness, hormonal changes, emotional factors, or even a change in the weather. A classic migraine attack can last for days and include a postdrome phase during which the sufferer experiences difficulty focusing, poor concentration and increased sensitivity.

Memory

A patient known as HM had brain surgery to control epileptic seizures in 1953, which involved removal of large areas of the hippocampus from both hemispheres of his brain. The operation successfully controlled his epilepsy but had a disastrous side-effect – it destroyed his ability to remember. Like a sufferer from severe Alzheimer's disease, HM was from that day unable to recall, people, places or events. Whenever he met someone, even though he had seen them many times a day, for months or years, he did not recognise them. The case demonstrated the essential role the hippocampus plays in memory storage.

Sleep and dreaming

Without sleep we would die. Sleep is essential for health and if we get too little, the brain becomes confused, and we lose the ability to think and remember. Yet our understanding of what makes sleep so important is still limited.

Sleep-wake cycles are controlled by neurotransmitters that act on areas of the brain. There is also a brain chemical, adenosine, which builds up in the blood during waking hours and begins to cause drowsiness. Once we are asleep it is gradually broken down. Dreaming is most apparent during REM (rapid eye movement) sleep, when the brain is highly active. In deep sleep, brain activity reduces but dreams still occur, often emotionally charged.

Unconsciousness

The conscious brain is responsive to sound, light and pain. But levels of consciousness can descend through confusion, delirium and stupor to coma, under the influence of drink or drugs, injury or infection, and tiredness. Coma results from damage to the parts of the brain involved in maintaining consciousness, especially the limbic system and the brain stem.

There are various degrees of coma, from shallow to deep. In the less severe forms the person may respond to certain stimuli, such as a sudden sound, with a turn of the head or small movements. In persistent vegetative state, the person may appear to sleep and wake and to move their eyes and limbs as if they were awake, but be unresponsive. In deep coma there is no response to stimuli although automatic movements such as blinking and breathing are maintained.

The Brain Book by Rita Carter (Dorling Kindersley, £25). To order this book for the special price of £22.50 with free P&P, go to Independentbooksdirect.co.uk or call 0870 0798897

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments