The battle against dementia: Could 2016 mark a turning point in the search for an effective treatment?

After years of disappointment, scientists may be on the brink of a breakthrough

The Queen sent almost 15,000 congratulatory messages to people celebrating their 100th birthday last year, compared with fewer than 3,000 in 1952, the first year of her reign. That is testament to progress – societies are successfully ageing across the world. But as we grow older, the risk of mental as well as physical decline grows too. While we may look forward to a card from the monarch and be resigned to failing eyesight and creaking joints, the prospect of a descent into mumbling incoherence fills us with terror.

The rise of dementia is one of the greatest disease threats the world faces. Less than a year ago, a major report spelt out the nature of the challenge and delivered the gloomiest possible prognosis. It showed that while the number of people affected is projected to almost double every 20 years – from 44 million globally today to 76 million in 2030 and 135 million in 2050 – the search for effective treatments was grinding to a halt.

The report by an expert panel, presented at the World Innovation Summit for Health (Wish) last February, explained why pessimism prevailed. It said: “Between 1998 and 2012, 101 unsuccessful attempts were made to develop Alzheimer's disease [AD] drugs and only three new medicines gained approval to treat symptoms. Indeed, the last new drug for AD – memantine – received regulatory approval more than 10 years ago. In the past 10 years, many promising disease-modifying compounds have been identified although none has succeeded in trials.”

Although a market worth billions awaits the manufacturer of a successful treatment, the high failure rate had caused pharmaceutical companies to withdraw from the search, it added. Indeed the poor success rate and huge costs – from $500m to $5bn to bring a new drug to the market – were deterring new investment. Between 2009 and 2014, large pharmaceutical companies halved the number of their active central nervous system programmes. The report warned of a “global economic crisis” and said that a “new, robust approach” was needed to attract new resources for research.

Yet just when the future seemed irredeemably dark, pinpoints of light have appeared. In the months since the report was published, there has been a flurry of positive new announcements on both the research and the policy fronts, causing the share prices of some drug-makers to soar.

In March, the first global ministerial summit on dementia was held in Geneva, hosted by the World Health Organisation. In October, the Dementia Discovery Fund was launched with $100m (£65m) investment from the UK Government, Alzheimer's Research UK and global pharmaceutical companies to speed up the discovery of new treatments. In November, David Cameron announced the first national Dementia Research Institute, to be led by the Medical Research Council, which is set to receive up to £150m by 2020.

Spurred on, perhaps, by this outpouring of largesse, two of England's most senior scientists – Professor Alistair Burns, national clinical director for dementia at NHS England, and Professor Martin Rossor, director for dementia research at the National Institute of Health Research – described in a recent blog posted by NHS England the new atmosphere of promise. They wondered if this was the moment when “we feel the hand of history on our shoulders” and concluded: “The one simple message is that we should be gearing up for a change – and not before time.”

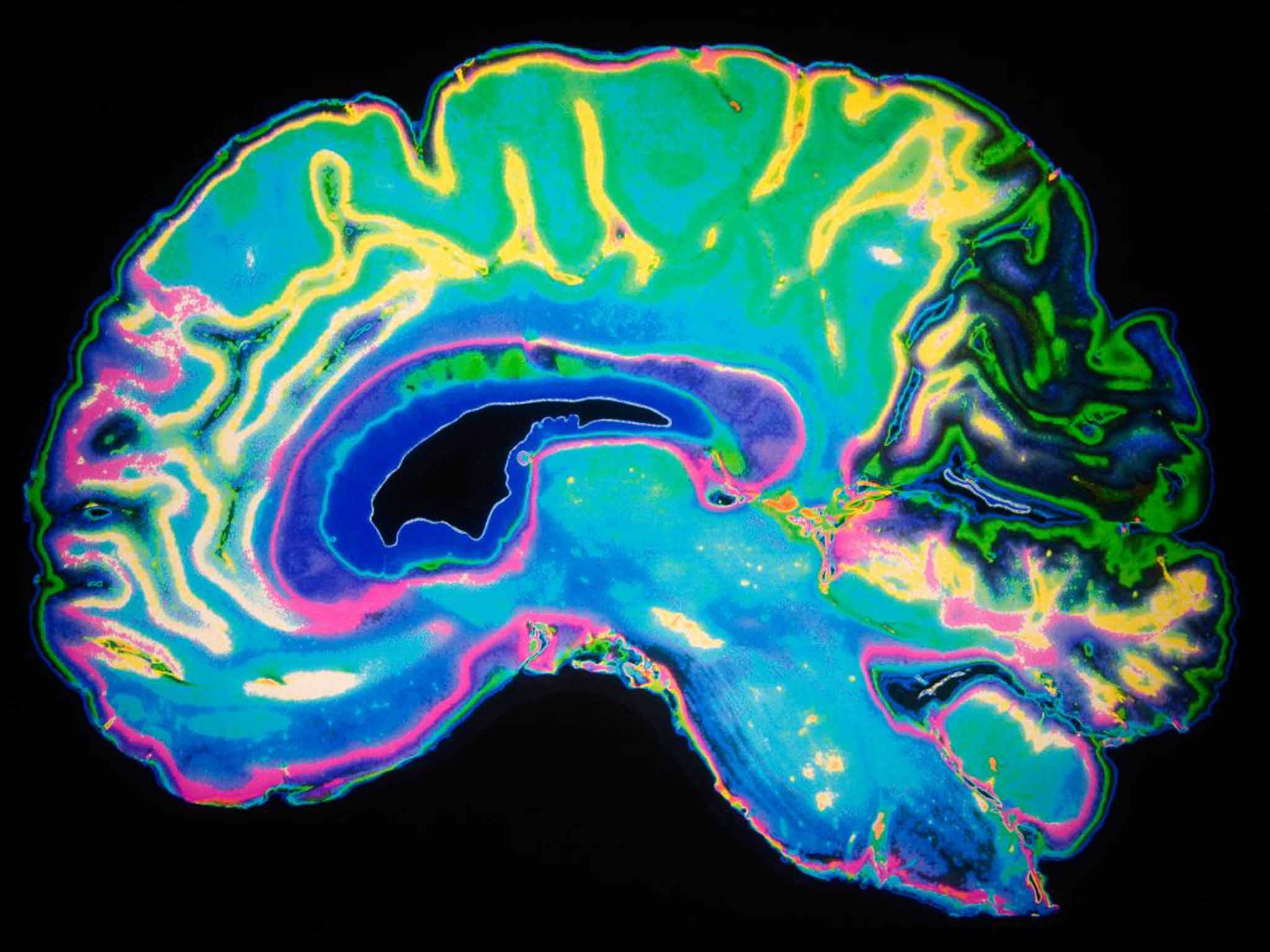

The focus of their excitement was the drug solanezumab (sola for short), a monoclonal antibody made by the drug firm Eli Lilly and targeted at Alzheimer's disease, the commonest kind of dementia, accounting for 60 per cent of all cases. Solanezumab dissolves the protein clumps that build up in the brains of Alzheimer's sufferers and are thought to be the cause of the disease. According to the theory, it is these protein clumps, or amyloid plaques, that lead to the death of brain cells, brain shrinkage and, ultimately, the distinctive symptoms of increasing forgetfulness, confusion and personality change that define dementia and blight so many lives.

Currently there is no drug that can halt this process. Existing treatments such as aricept, the best-known medicine for Alzheimer's, are symptomatic only, ameliorating the effects of the amyloid build-up, and aricept loses its effect over time. Solanezumab has generated excitement because it is the first drug to target the core pathological mechanism of the disease, rather than its symptomatic effects, and thus has the potential to halt its progression.

An initial trial of solanezumab was disappointing, showing it had no greater effect in slowing progression than a placebo. But the trial included patients in whom the disease was too far advanced to be susceptible to treatment, researchers believe. When restricted to those in the earlier, mild to moderate stages, it appeared to be effective, reducing the expected decline in memory by a third. A further trial involving people with mild Alzheimer's disease is due to report at the end of this year.

On this limited evidence of success, solanezumab may not sound like a revolutionary treatment. But seen in the context of the minimal impact of existing treatments, and the decades-long struggle to find an effective remedy, it feels to the scientists involved in the area like a new dawn.

Professors Burns and Rossor say that if the outcome of this year's trial proves positive, it will herald a “fundamental change in the way the disorder is approached”.

In the same way that the first drugs to treat cancer, depression and schizophrenia changed our attitude to those ailments, the same could happen to dementia: in place of resignation, there would be hope.

Speaking to The Independent, Professor Rossor, who was a member of the expert panel that produced the Wish report, says that a lot has happened in the past year and that the outlook has changed.

“If we are entering a new era of molecular diagnosis and treatment – even if we only see small effects – the approach will be different,” he says. “This is about shifting the focus from the behaviour [of those with dementia] and how to manage it, to brain function and how to treat it. It means shifting from therapeutic nihilism to therapeutic optimism. Nihilism is widespread.”

Psychiatrists who treat people with dementia will in the future need to work more closely with neurologists, who want to cure it, he says: “[Psychiatry and neurology] are two specialties separated by the same organ. They occupy different universes.” Solanezumab, which is given by monthly infusion, may help them to work closer together by presenting a new challenge to psychiatrists.

“Moving to this new era will mean adopting a different approach,” says Professor Rossor. “There will be more lumbar punctures [to diagnose Alzheimer's from analysis of the spinal fluid] and more infusions. That is not what psychiatrists do; it is what neurologists do. We will be where we were with cancer more than a decade ago. There will be small gains, and people will ask if the drugs are cost-effective. But then we can build on them: that's why we need a new approach.”

Solanezumab is the most advanced of the new treatments being tested for dementia, but it is far from the only one. Last month, researchers in South Korea reported that a chemical similar to taurine, the amino acid found in some energy drinks, cleared amyloid plaques from the brains of mice when added to their drinking water. The mice subsequently learnt their way through a maze faster, suggesting their memory was boosted. The research is, however, at a very early stage.

Last year, a small biotech company called Biogen reported that its drug aducanumab, which also targets amyloid plaques, had improved cognition in patients with dementia. It was a small, early-stage trial of 166 patients, but such is the fever around new treatments for dementia that the results caused Biogen shares to soar.

Enthusiasm was dampened when it emerged that the benefit was seen in those on the highest dose, which was also associated with serious side effects, including swelling of the brain. Biogen remains confident, however, and in September began recruiting patients for its final trial, involving 2,400 patients in 20 countries.

Several major companies are pursuing a new approach and investing heavily in the development of Bace inhibitors, drugs which, instead of targeting the amyloid plaques directly, target an earlier point in the process by blocking an enzyme (Beta-secretase 1) that triggers their build-up. Among those involved are several household names including Merck, which is the furthest ahead in trials, Novartis, Amgen, AstraZeneca and Eli Lilly.

It is Eli Lilly, however, that is generating most excitement. The company has seen its shares rise 26 per cent in the past year, boosted by the interest in solanezumab and the other dementia drugs in its pipeline, which include two Bace inhibitors and at least three other compounds.

In a presentation last month, the company said it was exploring another avenue of attack. Combination therapy – combining two or more treatments targeting different underlying mechanisms of the disease – could be the way ahead for Alzheimer's disease, it said.

In cancer, single-drug chemotherapy has long been superseded by multiple drugs given together, resulting in longer remission. HIV also proved resistant to single-drug treatment and was only defeated by triple therapy, transforming the disease from a death sentence to a chronic condition that patients live with rather than die from.

Professor Rossor says: “It is likely that combination therapy will be used in dementia as it is in cancer. Treatments will become more nuanced.” But he stark fact remains that, today, Alzheimer's disease is the only one of the top 10 leading causes of death that cannot be prevented, delayed or cured. This is the tragedy that played out in the recent film Still Alice. Treatment is commonly palliative and drugs are symptomatic only and lose their efficacy over time.

Repeated and costly failures in drug development have created funding fatigue. In 2013, leaders of the G8 countries united to increase research funding significantly. The UK established the World Dementia Council and pledged to double its funding by 2025. New ideas floated at an Alzheimer's Disease Society meeting in 2013 include crowdfunding, accessing sovereign wealth funds and pay-for-success programmes. The aim is to increase contributions from existing investors while creating new funding vehicles to attract new investors.

Encouraging further investment from drug companies in the face of immense costs, huge risks and onerous regulations is also critical. Exploratory discussions have been held by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency on how to achieve this, but co-ordinated action across regulatory agencies is needed to achieve real progress.

Still, a new programme from the European Medicines Agency allows staggered access to medicines based on a pre-planned, flexible timeline. It allows a limited number of patients who need medicines urgently to get early access to them so long as they are willing to accept the risk before studies have fully evaluated them. As evidence of their safety and efficacy accumulates, the drugs are gradually made available to more patients.

Whatever the outcome of these initiatives, an effective treatment for dementia is a long way off. But this need not lead us to despair. It is often suggested that there is nothing that can be done to halt, or even slow, the advance of dementia. But this is not true. There are things that we can do – both individually and collectively.

Individuals differ – but at whatever age your own brain starts to slow, it is vital to act early to prevent premature mental decline. Eating a healthy diet, avoiding obesity and getting plenty of exercise are all important to brain health, because what is good for our hearts is also good for our heads.

We also need to look after our brains – sharpen those chess skills, pick up that crossword and solve that puzzle. Scientists used to believe that cognitive performance began to deteriorate after the age of 60. But recent research suggests the deterioration may start sooner – from the late forties.

In Finland, a trial launched in 2009 showed that adults who were taught to eat healthily, participated in physical activities, received cognitive training and had regular medical check-ups over two years did significantly better on tests of memory, problem-solving and speed of thinking than their peers who had no intervention.

The message is: use it or lose it. Just as your body needs exercise, so does your brain – and, like your body, it requires proper nourishment. An active social life is also important – contact with other people is what keeps our brains stimulated, active and engaged.

For sufferers, simple measures can help. Almost one in 10 of those who consult a doctor with early signs of memory-loss turns out to have a problem that is reversible. The memory problems may be caused by a drug, a vitamin deficiency or depression: by addressing those causes, memory can be restored.

If dementia is confirmed, it is best that it is done sooner rather than later. That enables the individual to get help, obtain symptomatic treatment and plan for the future instead of languishing in a half-world, wondering what is happening to their mind and growing increasingly frightened and frustrated.

There are technological developments that are transforming lives by enabling dementia sufferers to stay in touch with their families and maintain as much independence as possible in dementia-friendly communities. Social innovations such as “dementia cafés” help to build a sense of community.

Better understanding of risk factors would allow the population to be sub-divided according to their risk. That in turn would allow diagnostic and preventive measures to be focused on those at the top end of the scale with the highest risk.

Improving care and understanding of the condition could in these ways deliver immediate results. The message is: we are not powerless. There are measures that we can take to stem the advance of the degenerative brain condition that strips sufferers of their dignity and humanity.

Evidence that we can roll back the tide came last month in a study of 15,000 older people published in The Lancet, which showed the onset of dementia was delayed by four years in men and three years in women, compared with 20 years ago. Possible explanations are improved diet, better fitness, longer education or increased treatment for conditions such as high blood pressure and high cholesterol. But of one thing we can be sure: ageing well is possible – and a goal worth fighting for.

Crosswords and Puzzles from The Independent can be solved here

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments