TV 'self-experimenter' Dr Michael Mosley plans his nastiest challenge yet: infecting himself with tapeworms, leeches, and even malaria

It's a documentary that promises to be fascinating – but you'd be well-advised not to watch it over dinner.

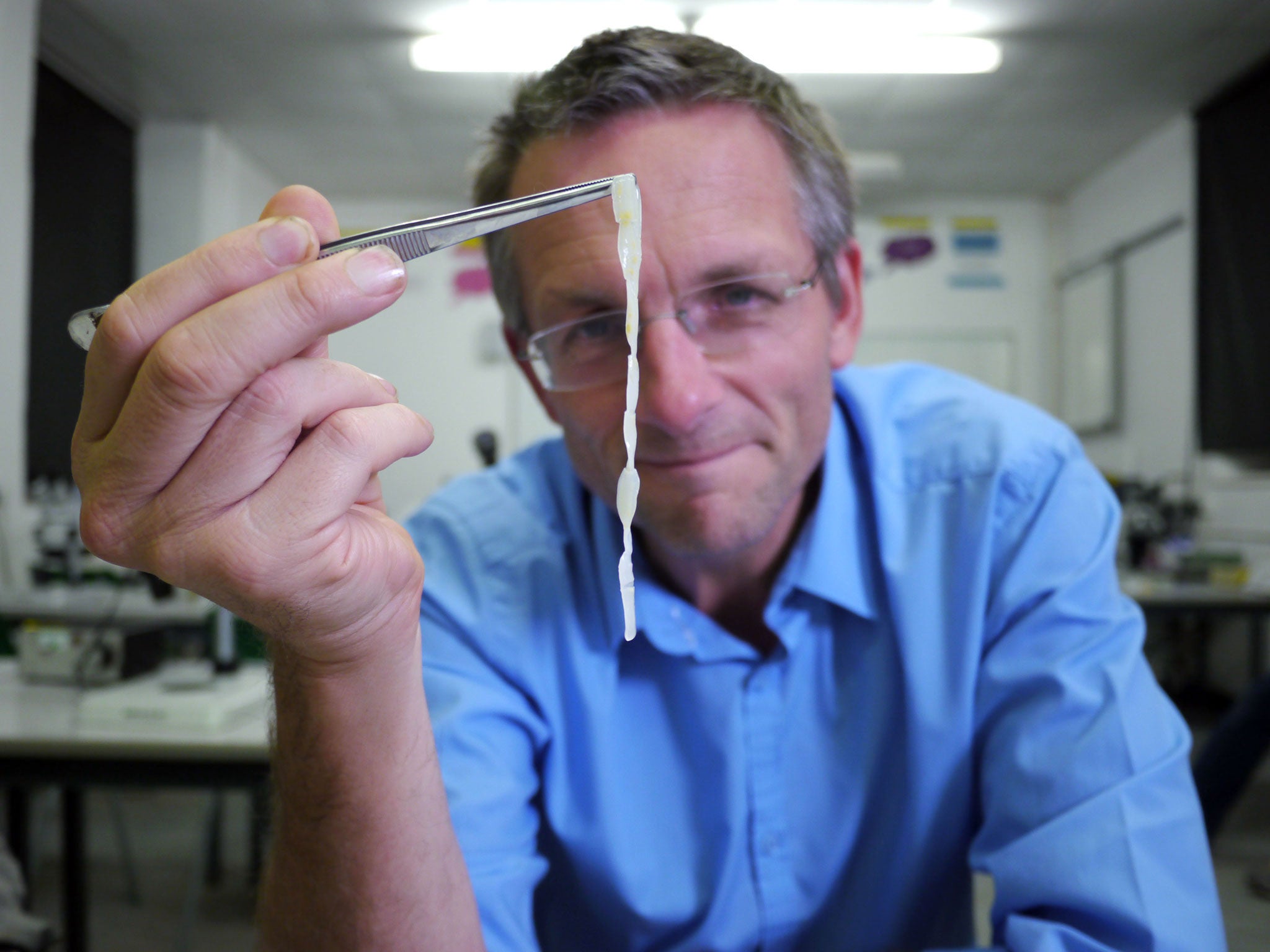

For his latest programme, Dr Michael Mosley, TV's most recognisable “self-experimenter” has spent the past few months deliberately infecting himself with some of the most unpleasant parasites known to man – partly to help advance medical understanding, partly, he admits, “because it's just interesting”.

Infested! Living with Parasites will air on BBC4 in February. In it, Dr Mosley – perhaps best known as the man behind the 5:2 “fast diet” and “fast exercise”, both of which he investigated by allowing TV cameras to film his own personal experiments – has intimate encounters with tapeworms, head lice, leeches, and even subjects a test tube of his own blood to malarial infection.

His findings explode some long-standing medical myths (tapeworms, for instance, are no good at helping you lose weight) but also uncover evidence that some parasites might have the potential to actually do us some good.

In order to reliably infect himself with tapeworm, which is now very rare in the UK, Dr Mosley travelled to Kenya where his team sourced cysts from the tongues of infected cows at an abattoir. These cysts form in infected cattle and contain what is effectively a baby beef tapeworm – a relatively harmless type that can nevertheless live for up to 20 years and grow to several metres long if left alone. Dr Mosley swallowed three of them.

After six weeks he ingested a pill-sized remote camera to see whether the tapeworms had taken up residence and was delighted to discover – via a live video link on his iPad – that he had “triplets”, living and growing in his gut.

However, there was no evidence that having the worm reduced his weight, as was traditionally believed.

“My weight if anything went up a bit,” he said yesterday, announcing his findings at the laboratories of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

“The theory is that the tapeworm actually encourages you to eat more in order to feed it,” he said. “There are subtle and insidious ways in which parasites influence your behaviour. It is theoretically possible that tapeworms influence your gut hormones. I put on about one kilogram – so as a slimming device it is utterly useless.”

As for the risks involved, he remains admirably sanguine. Beef tapeworms do little damage early on in the infection, although they can disrupt digestion if left to grow.

“The main negative effect is that after about 10 weeks, segments of the tape worm can start crawling out of your bottom,” he said. “They have male and female parts and carry eggs. They can literally crawl out. I have spoken to someone who said they started crawling out of his trouser leg while he was driving down the motorway.”

Other forms of tapeworm – such as the pork tapeworm – are even more unpleasant and can infect the brain, causing epileptic fits. Modern hygiene and food preparation makes contracting such parasites very rare in the West, but they remain a problem in many developing nations. Dr Mosley's stool samples are being investigated at the University of Salford to establish whether there are any indicators of infection that could be, in the future, used to diagnose people earlier.

“Parasites are very prevalent in other parts of the world and are very destructive. It's a very under-researched, under-funded area,” he said.

The experiment – the most gruesome of several carried out for the programme – also investigated the “hygiene hypothesis”, the increasingly well-established theory that the decline in the number of parasites humans encounter has, by suppressing the development of our immune systems, had the side-effect of increasing our vulnerability to allergies and conditions like asthma

Dr James Logan, senior lecturer in medical entomology at LSHTM, who also took part in the documentary, found in a previous self-experiment that his bread allergy was temporarily cured after he infected himself with a hookworm – a parasite common in developing countries, which burrows under the skin and then works its way through the bloodstream, via the heart, into the lungs, where it is coughed up and then swallowed into the stomach.

Despite feeding on blood from the gut wall, they can in fact have some benefits thanks to the saliva they produce, which spreads through the bloodstream, modulating the immune system and suppressing the immune response that leads to an allergic reaction.

Although parasite therapies for allergy are still firmly categorised as experimental, Dr Logan believes they may have a future.

“We evolved with parasites,” he said. “It's only recently that we've had the medication and hygiene to get rid of them. Our bodies are designed to live with parasites. There are some hypotheses that the reason we reason we have more allergies, more asthma today, is because of a lack of parasites. Just by studying them and understanding their fascinating biology we can find thing that benefit ourselves.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments