Right to die: Arguments for and against

Friday's debate on assisted dying will be one of the most moving ever held in the House of Lords

Here is what some of the speakers intend to say during the debate, after the Prime Minister admitted yesterday that he was “not convinced”.

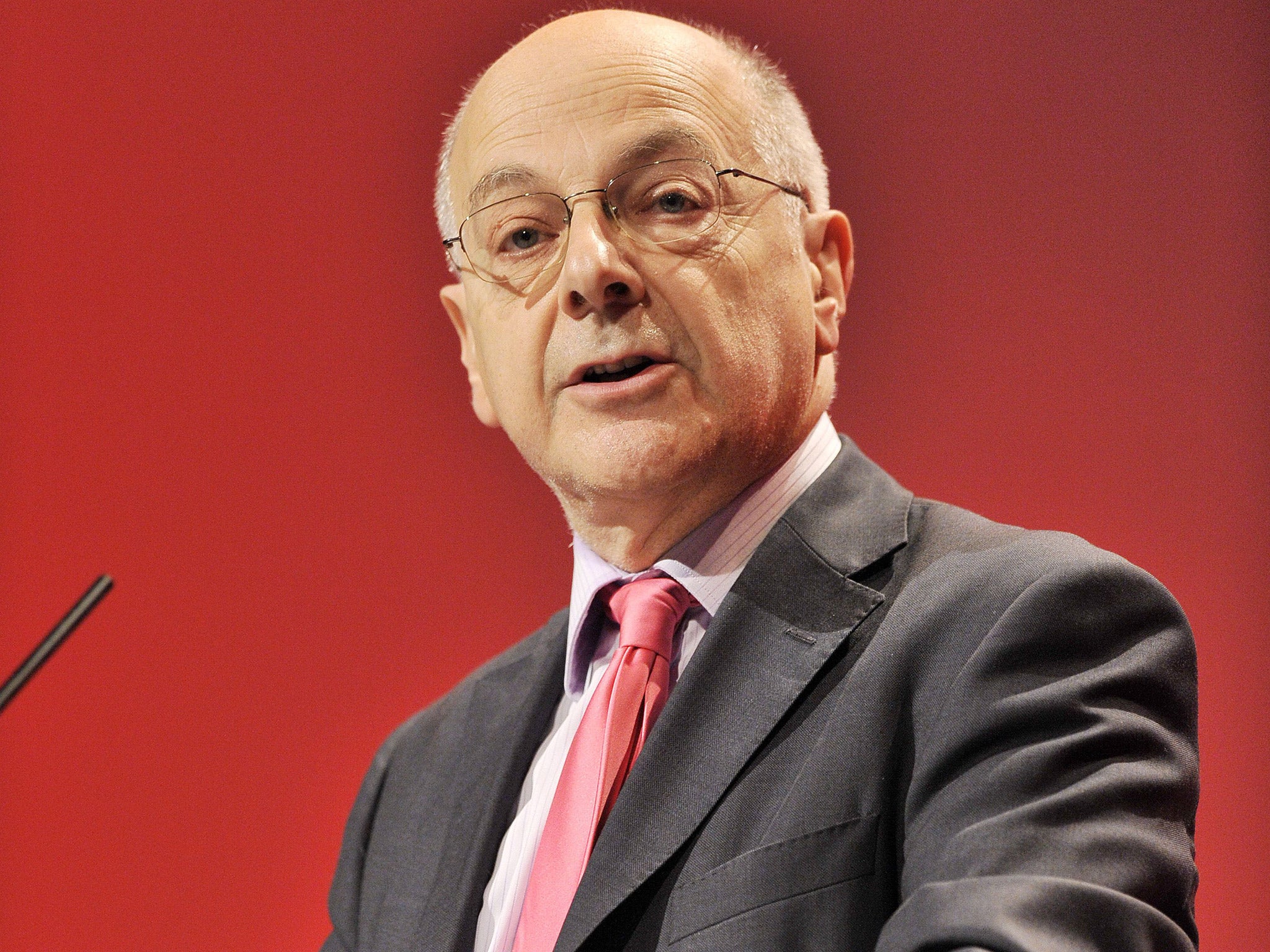

Lord Beecham (Labour)

I will be supporting Lord Falconer’s Bill on Assisted Dying – in part because I know that my wife, who died of cancer four years ago, would have wished me to do so.

When she was diagnosed with incurable bowel cancer, she made it clear that if she were to suffer great pain she would wish to be helped to end her life. In the event, with superb care from the NHS and St Oswald’s Hospice in Newcastle, her suffering did not become extreme. She lived as fully as possible during the two years of her illness.

Nevertheless, should her pain have become unbearable, she should have had the choice of bringing it to an end.

Lord Hylton (Crossbench)

I think it’s a bad and dangerous Bill and have always felt that. The safeguards proposed are quite inadequate – that’s the opinion of many eminently qualified doctors and other physicians. I have received letters from all over the country against the Bill and the evidence from countries where therapeutic killing is legal is far from reassuring.

Baroness Blackstone (Labour)

To stop dying people ending their lives when they are suffering unendurably is a denial of human rights. Public opinion now strongly favours assisted dying and surveys show that a majority of practising Christians and Jews support it.

I have had many letters from people who have had to watch people dying in agony and begging to be allowed to die. Some sought relief by shooting themselves or throwing themselves in front of a train. Such deaths should not be allowed to occur in a humane and civilised society.

The Rt Rev the Lord Bishop of Carlisle

I and my fellow bishops in the Lords are all opposed, firstly because of our fundamental belief in the intrinsic value of every human life.

We appreciate the motive behind the Bill, but we feel this compassion is focused on a few cases and doesn’t consider some of the most vulnerable people in society – especially the elderly and disabled. They will feel under enormous pressure if this Bill is passed. We know that 500,000 elderly people are abused each year, both physically and mentally, by relatives and carers. Some will feel like burdens on society and to their families. They will be under pressure to end their lives prematurely.

The proposed safeguards are inadequate. They limit assisted suicide to people who have six months left to live but that is notoriously difficult to determine; whether someone is in “their right mind” is also difficult to determine.

We are also worried about the doctor/patient relationship. Many doctors argue the Bill will put them in a vulnerable position. Finally, it is always dangerous to make laws according to a very few, very difficult cases, especially on matters of life and death.

Lord Warner (Labour, former Health Minister)

Will Parliament give sufficient weight to the harrowing personal accounts described in the many letters sent to some of us? Here is a sample from my correspondents.

There is the 88-year-old woman from the Lake District wondering how much longer she can cope with caring for her husband with motor neurone disease and listening to her 93-year-old priest brother in a care home asking for help “to go home” as he puts it.

Then there is the daughter from Yorkshire eaten up with guilt because she could not help the merciful release of her terminally ill father who was “saved” three times by doctors from dying of pneumonia.

Perhaps the most harrowing account was from a man from Cambridgeshire who found that his elderly terminally ill mother had managed to hang herself in the middle of the night because she could not bear her suffering any longer. He and his brother remain haunted by this and their inability to help.

All the letters and emails I have received have been in favour of the Bill. Many are handwritten. Often they are from people in their seventies and eighties. Virtually all the letters support stringent safeguards and none are arguing for euthanasia. They have highly individualised stories to tell, including the man whose 87-year-old mother was evicted from a nursing home simply for asking about assisted dying.

As parliamentarians we should listen to the anguish and concern of these very thoughtful people.

Lord Alton of Liverpool (Crossbench)

I do not believe the law should license doctors to involve themselves in knowingly and deliberately bringing about the deaths of some of their patients. It places responsibility for assisting suicide on the shoulders of a profession that does not want it and most of whose members would have nothing to do with it.

The Bill itself is flawed. It contains no safeguards to protect the vulnerable, just a vague promise of safeguards at some future date. It defines terminal illness in such a way as to encompass large numbers of people with chronic conditions and disabilities as well as terminal illnesses. It contains no compliance system – not even a requirement for a doctor supplying lethal drugs to report.

Lord Shipley (Liberal Democrat)

We need a debate and if there is a vote, I will vote to consider the Bill further at Committee Stage. This is important given public opinion. But I am very concerned that individuals who are terminally ill may start to feel an increasing burden on those around them. And without the support of the medical profession, it is hard to see the Bill completing its passage.

Baroness Hollins (Crossbench)

Deciding not to continue life-saving and burdensome interventions is not the same as assisting someone to kill themselves. The arguments made by Archbishop Carey and Archbishop Tutu are confusing and do not seem to support assisted dying – rather they are arguments about not prolonging life.

I think we should campaign for universal palliative care and better support and friendship for people who are terminally ill. Doctors are notoriously poor at predicting death until the final days of someone’s life. It’s also hard to predict how any of us will react to a diagnosis of a terminal illness, both when the “bad” news is broken and later as the implications sink in. However, the impact of suicide on families, whatever the circumstances, is hard to underestimate.

This is a public safety issue and must not be decided on the interests of a few.

Baroness Warnock (Crossbench)

When opponents speak of “life being precious”, they forget that life isn’t a kind of stuff, like water, which has an objective value, and which we can be urged not to squander, but to preserve. If a human being has got to the state where her life is hateful to her, no one else can insist it is valuable. It is for her to judge its value.

I do not understand why it is thought that people who ask to be helped to die should not have as at least part of their motive the wish to spare their family expense and the possible disruption of their lives. All one’s life it has been taken for granted that we will act for the benefit of our children. Why should it be assumed that there is something wrong with these motives (or something fake about them) only when one is dying?

Baroness Greengross (Crossbench)

I have a right as a mentally competent adult under English law to end my life. If I’m dying and decide I can’t endure my suffering any longer, but can’t manage to end my life sooner than it would end anyway without some help, then I’m discriminated against and anyone who wants to help me risks prosecution – that is totally unacceptable.

Baroness Hayman (Crossbench)

I was undecided when Lord Joffe tabled his assisted dying Bill in 2004. I served as a member of the Select Committee (on Assisted Dying for the Terminally Ill Bill), so I visited Switzerland and Oregon and talked to people at the hospices, discussed assisted dying with doctors, pro and against, and that convinced me it was possible to have appropriate safeguards to allow people who are in obviously desperate circumstances to have a degree of control over their lives during their last few days or weeks.

The thing that struck me the most was the number of people who gained comfort from the knowledge that the option was available. In Oregon every year the number of people who speak to their family, friends or doctors about it is one in six, yet only one in 500 people actually have an assisted death – so that says people are not under pressure to do it, and also that knowing there is a choice allows people to continue to live.

One of the saddest things is that people go to Switzerland earlier and earlier than they would want to because they feel like they have to go while they are still mobile. If they stayed at home and knew they had the option of an assisted death, they could take it at home with friends and family in their own surroundings.

Baroness Tanni Grey-Thompson (Crossbench)

It is sadly not simply a case of suffering versus compassion. It is far more complex issue than that. In other jurisdictions that have some form of assisted suicide, pain is near the bottom of the reasons that are given. Being a burden to others is at the top of the list. That is a very sad state of affairs.

Baroness Finlay of Llandaff (Crossbench)

I do not support what is being called “assisted dying” – or, in plain language, physician-assisted suicide. Assisting suicide is not a proper part of medical care. Doctors have a key role in preventing suicides: it is perverse to ask them to do an about-turn and give some of their patients the medical equivalent of a loaded gun.

The majority of doctors are opposed to a change in the law. They see patient vulnerability every day and at first hand. Today, most doctors know little of their patients’ lives beyond the consulting room or hospital bed, and cannot know whether a request for assisted suicide is a truly settled wish, free from untoward influence.

Baroness Meacher (Crossbench)

Patient choice is a fundamental principle of modern medicine recognised throughout our lives. But at the very end of life, the taboo about death has led us to take away this right when it is most needed. Dying patients in the UK often go to their graves with their fears and hopes unspoken.

In Oregon very similar legislation enabling physician-assisted dying as a legal end-of-life option has been in place for 17 years. The Executive Director of the Oregon Hospice Association for 20 years, who opposed the legislation at the start, now supports it strongly. She is entirely satisfied that the safeguards (similar to those proposed here) are sufficient to ensure genuine patient choice.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments