The moment we told my 10-year-old daughter she had HIV – a mother’s story

'Have you heard of HIV before?' Biting her top lip, she shook her head – no

The fifth-grader with cornrows stepped from an elevator at Children’s National Medical Center and walked over polished tile floor she had first crossed in a baby carrier. She rounded a corner and opened the door to Room 3400, its purposely generic name inscribed on a white panel: “MEDICAL SPECIALTIES.”

Her adoptive mother, her right hand on a metal cane, limped through the crowded waiting room as JJ pulled a Care Bears coloring page from a plastic file and sat down at a miniature table. She began outlining stars with a blue crayon, then she spotted a pair of familiar performers.

“Mommy, the clowns,” JJ said, pointing. “They were here last time.”

The 10-year-old was wearing three puffs of a cherry blossom perfume and a kaleidoscopic dress she had pressed the night before. She looked forward to these visits to the renowned medical center in Northwest Washington, in part because she knew a treat from McDonald’s or Checkers would follow and, in part, because amid a young life rife with turmoil, she found reassurance in her hospital routine.

She knew her measurements would be taken, and she hoped to crack 5 feet but not 100 pounds. She was ready to breathe in and out, and then, without prompting, produce a vein from which blood would be drawn, a ritual she had mastered before learning how to steady a bicycle. She expected to be reminded of the bad germs in her body and told, yet again, that she must — must — take her medication every day.

What JJ did not expect on that sweltering summer morning, 3,787 days after her diagnosis, was the conversation that awaited her in exam room No. 4.

Since the AIDS epidemic erupted in the 1980s, hundreds of children born with HIV have been brought to this hospital for treatment by medical specialists who become surrogate aunts and uncles. The doctors, nurses and therapists buy them birthday gifts, attend their graduations and teach them how to take pills. They monitor their life-defining numbers and strategize against a relentless virus for which no cure exists. They keep them alive.

They do all of this without telling their youngest patients why. And when the time comes to tell them as they reach puberty, the staff plans for weeks how to do it, debating whether the kids are ready to know — whether they can handle it.

And now they hoped that JJ could handle it, because she was about to learn the truth.

The night before she walked into the waiting room, her mother, Lee, had lain in bed and prayed. Her stomach tightened as JJ, who often climbed in with her, slept on Lee’s shoulder. She knew what was at stake. Because of the vicious stigma still attached to HIV, doctors at Children’s would deliver the news with a pair of contradictory directives: Don’t be ashamed, but keep the virus a secret.

Her baby girl had long suffered through torrents of fear and sadness. How JJ would respond to the disclosure about her illness, no one knew.

“Let her be okay,” Lee had asked God in the darkness and again as her daughter was called to the back of the clinic.

'Her eyes pierced my soul'

JJ was near death when she arrived at Children’s as an infant.

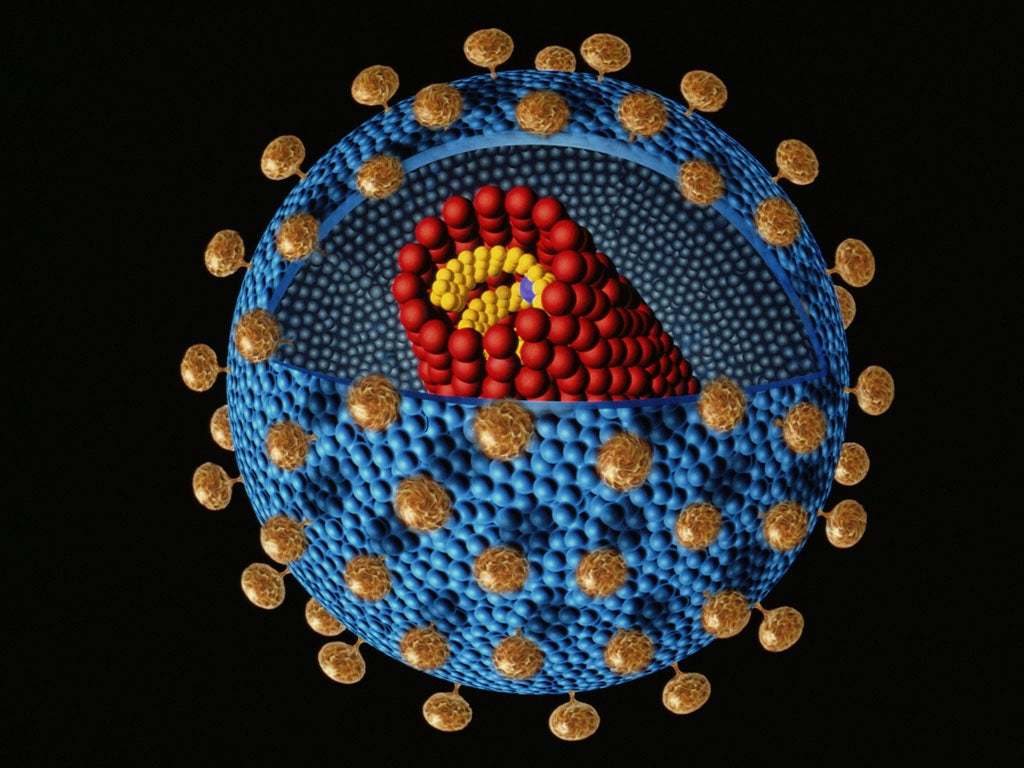

Deprived of oxygen and breathing rapidly, she received antibiotics through an IV for 21 days to treat a form of pneumonia that kills more HIV-infected babies than any other condition. Her viral load, which is the amount of HIV in the blood, exceeded 2.6 million copies — 130,000 times the level at which someone is now considered “undetectable” and highly unlikely to spread the illness.

At the time, Lee was a bus driver and foster parent. The seventh of 12 kids, caring for children had been her life’s purpose since her mother gave her responsibility over a baby brother when she was 7.

Lee, a stout woman with dark eyes and an easy laugh, raised three sons before fostering more than a dozen kids. She is stern but compassionate, not reluctant to raise her voice at a child but just as quick to wrap one in her arms.

Lee was already caring for one of JJ’s older sisters when the foster agency called again. There was a younger sibling, the woman explained. An infant.

Okay, Lee said.

And the girl has pneumonia.

Okay.

And another thing: “She’s HIV positive.”

Back then, Washington was still struggling to control the disease’s spread. Revolutionary drugs had reduced the risk of mother-to-child infections to less than 2 percent if the virus was discovered before delivery. And yet, dozens of babies continued to be born with HIV in the nation’s capital, where, at the time of JJ’s birth and diagnosis, epidemic rates compared to those in parts of West Africa.

But the disease didn’t frighten Lee. Her oldest son had contracted HIV as an adult, and an AIDS-related illness had killed her ex-husband, whom she cared for as his body failed.

Yes, she told the agency. I’ll take the infant.

The girl was bald, underweight and wrapped in a tiny hospital gown when Lee first saw her. “Her eyes,” she said, “pierced my soul.”

Days later, she clothed the 4-month-old in a pink dress with matching socks, shoes, sweater and cap, then drove her home.

Lee learned that JJ and her siblings had been taken from their biological family after allegations of molestation against an older brother. Her father was a convicted murderer, and her mother had abused drugs. Lee never found out whether the woman knew she was HIV positive at the time of JJ’s birth.

Relatives made little effort to get the girls back, Lee said, so when JJ was 3 and her sister was 9, she adopted them both.

Lee told family members about JJ’s condition. Some demanded that she stay away from their children. “They didn’t understand,” Lee said.

To her, JJ was just another kid who needed love. “Lady Bug,” Lee called her then. JJ was trusting and kind, and her head’s favorite spot was against her mom’s shoulder. At 3, she sang gospel hymns in church and danced in front of the pulpit. At 5, she made silly videos in which she told stories about cucumbers and wiggled to a Waka Flocka Flame song. She feared dogs and caterpillars and the mechanical mouse at Chuck E. Cheese’s, but never the needles that took her blood. She mastered a pose that she still employs today: half-turned, hand on hip, elbow out, head cocked down and a grin so immense it makes her cheeks swell like plums.

She was happy, Lee said, except when she wasn’t.

JJ threw violent tantrums, breaking cabinet doors, busting holes in walls, smashing a laptop. A few years ago, her older sister, in a moment of spite, revealed to JJ that Lee wasn’t her real mother. The girl hated that.

“You don’t love me,” she would say to her mom. “I’m just adopted anyway.”

One day, JJ erupted in their kitchen. She screamed and threw cups. She stomped on the floor.

“I want to kill myself,” the girl shouted.

She was 7.

When she threatened suicide again after being bullied two years later, her psychiatrist — who had already prescribed her ADHD medication — put JJ on Lexapro, an antidepressant that Lee crushed and mixed into apple sauce.

JJ had long known that something else was wrong with her — that no one should touch her blood. She had seen doctors every few months since birth and taken medicine since a plastic syringe delivered it to her mouth. “A rare blood disease,” Lee had told her, and JJ never pressed for more details.

Children’s doctors typically tell kids their diagnosis at 12 or 13, before any sexual activity begins. But in March, JJ overheard her sister use those initials — HIV — on the phone. Lee panicked.

The timing was horrendous. Lee, now a retiree in her 60s with two bad knees, was also dealing with JJ’s sister and a granddaughter she had taken on, both unruly teenagers whose defiance had rubbed off on the girl. Teachers complained that JJ had lost focus at school. They had found her wandering the halls, alone. She was failing both math and English and on track to repeat fifth grade.

But Lee saw no alternatives. She and JJ’s doctors feared a “tragic” disclosure, in which children learn of their illness in a way that could forever damage how they view themselves.

They decided JJ had to know.

Days after that determination, she came home from school, ate a slice of Domino’s pizza, and then, at her mother’s insistence, opened her math assignments on the family’s aging computer.

She worked through a few problems in the living room of their three-bedroom townhouse outside Washington, until she realized Lee had stopped watching. JJ switched to a video game, then a quiz about her favorite show: “Which SpongeBob SquarePants Character Are You?”

“What do you say when life’s not going your way?” one question asked.

“Barnacles!” she clicked.

“What’s your favorite word?”

Not “Wumbo.” Not “Meow.” Not “Quiet.”

“Fun,” she answered.

“How do you feel most days?” the last question inquired, displaying a series of SpongeBob’s expressions: afraid, angry, confused, sad.

Another depicted a bright-eyed, toothy smile.

She clicked it.

A battle over pills

The struggle with her medication began when JJ was 4.

Like every child born with HIV, she was given liquid antivirals. Early on, though, doctors introduced pills into her regimen. Some kids adapt immediately. Others, including JJ, take far longer.

At age 5, she was on three medications: two liquids and an oval-shaped pill about the size of a Hot Tamale candy. JJ often spit out the tablet or threw it up, but the liquid form of that drug, Kaletra, had a flavor one nurse described as a mixture of earwax and Bacardi 151 rum. She couldn’t stomach it.

Doctors have since altered JJ’s medications at least seven times, according to the girl’s vast medical record, a literal testament to the efforts Children’s staff has made to keep her healthy. The decade it covers fills hundreds of pages, many of them bound in a tattered baby blue file as thick as a Bible.

One of JJ’s doctors, Kathy Ferrer, has repeatedly explained how essential the drugs are to her health. The physician, who once worked in Africa’s AIDS-ravaged Lesotho, draws a smiling, long-haired stick figure, then surrounds it with circles. These cells are “soldiers,” she tells JJ. They protect you. She slashes X’s through several circles, illustrating that germs destroy the soldiers. And what do the medicines do? They destroy the germs.

After JJ’s seventh birthday, Ferrer estimated she was taking between 50 percent and 75 percent of her doses, a level of adherence the doctor wrote was “very dangerous” because it allows the virus to mutate and become permanently resistant to the drugs.

It’s not easy, her doctors say, to convince children who don’t feel sick today that, without medication, they will feel sick someday later.

Kids with HIV can live into their 70s if they adhere to their drugs. It seems simple, but denial, depression and rebellion lead some to refuse treatment, experts say. In the past year, two of Children’s young adult patients have died because they stopped taking their medicine. Others are on the path to that same fate.

Doctors eventually placed JJ on a “holding regimen,” a single, palatable liquid that they hoped would keep the HIV under control until she could manage pills.

At the hospital, she practiced swallowing candies — cake sprinkles, Tic Tacs, Smarties — meant to imitate those pills. At home, Lee had tried everything she could think of: bribing with stickers, cutting tablets, applying a grape “glide” spray to make them go down more easily. If JJ could stay consistent for a single week, her mother often promised, she would get to pick out a treat at the dollar store.

Nothing worked.

Battling with her daughter over the medications — morning and night, year after year — exhausted Lee, as it does many parents.

“Adults themselves are horrible at taking medicine twice a day for 10 days,” Ferrer said. “This is a lifetime.”

By last summer, JJ’s viral load had crept above 43,000. Her CD4 count, a measure of the immune system’s health, had fallen from an all-time high of more than 2,000 to under 400. AIDS is diagnosed when that figure reaches 200.

Would telling her she has HIV help?

For some kids, Ferrer said, learning provides them with new resolve to follow their treatment. For others, it crystallizes their hatred for the medication, a daily reminder of what forever makes them different.

With disclosure just weeks away, JJ had begun spending weeknights at the home of her godmother, Nicole, a married mother of three whom Lee hoped could help the girl improve her grades.

Nicole had set strict rules and seen results. JJ finished her homework, helped care for Nicole’s young kids and, usually, took her liquid HIV medication — as well as her tiny ADHD and depression pills — without resistance.

But, one April morning, Nicole had also caught JJ carelessly swallow too much of the drug. It disturbed her. She had pushed JJ to act more responsibly, and, in that moment, she became convinced that the truth would make her goddaughter understand the medication’s critical importance.

Nicole decided to tell JJ she had HIV instead of waiting for the doctors to do it.

She searched online for how to talk about the issue. She found video of an 11-year-old who, in 1996, had articulately discussed her illness with Oprah and was now excelling as an adult.

When her goddaughter returned home from school that afternoon, Nicole took her laptop up to JJ’s room.

She was sitting on her bed, coloring. Nicole told her that soon the doctors would explain why she had to take the medicine. So, her godmother recalled asking, do you want me to tell you why right now?

JJ stopped coloring. She stared at the floor, thinking, then looked up.

“No,” she said. “I don’t think I want to know.”

The choreography of disclosure

In the infectious disease conference room, three piles of baby blue files were stacked on a long wooden table.

Ferrer and nine others gathered around it, as they do every week, to discuss their HIV-infected patients: a pregnant teenager concerned about her unborn child; a boy whose father still didn’t understand which pills his son needed; a stubborn young woman who the staff had asked to sign a contract committing to take her medications.

Chenere Evans, a psychologist, mentioned a 14-year-old mentally disabled boy who had announced to his class that he had HIV. Heads shook around the room.

At last they came to JJ.

She is among the 20 percent of Children’s 340 HIV-positive patients younger than 13. And with fewer than 200 babies a year now born with the virus nationwide, the people in that room hoped that the impending discussion — one they’d had so many times before — would no longer be necessary in a decade.

Michael Mancilla, JJ’s social worker, asked whether she would be told of her illness at a single appointment or in stages over several weeks.

“Truthfully, with this kid I would do slower,” said Kim Bright, a 29-year veteran nurse wearing Cookie Monster scrubs.

“Yeah, I think slower,” Evans, the psychologist, agreed.

They all knew her history, but their concerns about JJ were much like their concerns for every kid. How would she react? Who would she tell? Would disclosure drive her closer to or further from treatment?

The staff understood what was possible.

They remembered the young man whose friend tweeted that he was sick with “the sauce” — a slang term for HIV. Who, after refusing medication for years, lost his vision and suffered micro-lesions on his brain. Who deteriorated in the hospital for eight months before dying in February at age 23.

But they also knew the 21-year-old woman who, a decade after being told, has an undetectable viral load. Who bore a healthy infant and takes her medicine every night. Who grew up to be a pharmacy technician and work with teens afflicted with the same disease.

For JJ, Ferrer and her colleagues decided to proceed with disclosure in a single appointment but also to assure Lee that they could immediately provide additional support if the girl needed it.

Ferrer reminded them that the doctor delivering the news, Natella Rakhmanina, had disclosed HIV to dozens of children and would know how to deal with JJ’s reaction. Born and raised in Russia, Rakhmanina believed in a direct approach: Tell them what they have and what it means. Kids, she thought, could sense insincerity.

“No change in the meds?” Mancilla asked.

“No change in the meds,” Ferrer said. “She’s on the holding regimen.”

The doctor noted that JJ’s numbers had gradually worsened.

“So maybe,” she added, “disclosure could be helpful in terms of getting her to understand why she needs to take these big huge pills, which she hates taking.”

‘She’s just 10’

Six days before the appointment, Lee walked into one of JJ’s classrooms, and her daughter smiled.

“Mommy, I got something to show you,” she said, pulling a certificate from her bag.

“Honor Roll,” it read. JJ was going to pass fifth grade.

“I’m so proud of my baby,” Lee said later in the van, as they headed to meet the girl’s psychiatrist.

The whole school, JJ explained, had gathered that day for an awards ceremony.

“Was you shocked?” Lee asked and looked at her daughter in the rearview mirror.

“Yeah,” she said, chewing on a grape in the back seat. “I was just sitting there because I thought they called someone else’s name.”

JJ glowed, her smile affixed in place.

Then, as the van pulled into the office parking lot, her older sister whispered a barb.

“Shut up,” JJ snapped. Her arms crossed and jaw clenched.

“I’m not having that attitude,” Lee warned the girls. “Straighten it up.”

Inside the waiting room, where the air conditioning had stopped working, JJ slumped into a chair and laid her head on the armrest, suddenly despondent. “Judge Judy” blared on a nearby TV.

Lee, who paid for all of JJ’s treatment through Medicaid, walked back into the doctor’s office to discuss the upcoming disclosure.

“I’m thinking things will be okay, but you just never know,” Lee said. “She’s only 10. We got to remember. She’s just 10.”

On their way out, they saw her therapist, whose office was down the hall.

“How you doing?” he asked JJ.

“Good,” she said, her eyes down.

In the elevator, JJ put her head on the handrail.

“Did you take your medicine yesterday?” Lee said, referring to her depression and ADHD pills.

“Yes.”

“No, you didn’t.”

JJ groaned and pounded her foot on the floor. What was one of the best days of her year had abruptly imploded. These mood shifts were what made Lee most nervous about how JJ might react to the diagnosis. Her mother couldn’t predict this or control it. And neither, she knew, could JJ.

Back in the van, the girl leaned her seat back and closed her eyes. On the center console in front of her was the honor roll certificate, which Lee had carefully tucked under her Bible. Atop the book’s front cover, a word was etched in bold letters: “HOPE.”

‘Have you heard of HIV?’

Natella Rakhmanina opened the door to exam room No. 4 and pulled two chairs next to the medical table, facing them toward each other.

At a desk, JJ filled in red and blue hearts on her Care Bears coloring page. Next to the sheet was a frilly bow that resembled a pink peony flower. Another Children’s staff member, knowing what was to come, had given her the gift that morning. Smitten, JJ gasped when she first saw it.

Rakhmanina asked her to sit.

Why, the doctor soon asked, did JJ think she took medication?

The girl stared up at the cream-colored wall. The room chilly, she had spread a hospital gown over her lap, and now it hung down to her glittery black sandals.

“So I won’t, umm, so I can stay healthy and I won’t die and that I can . . .” she paused. “Stay alive.”

Lee watched in silence, leaning forward with her arms crossed and mouth taut.

Rakhmanina, her accent thick, explained on a sheet of paper that JJ’s condition attacks the cells that defend against infection. To this JJ nodded, yes. She understood.

“This virus is called, and you’ve probably heard this name already: HIV.”

JJ’s eyes fixed on the paper as Rakhmanina wrote those three letters. The girl said nothing.

“You have quite a bit of virus in your blood,” she said, explaining that though JJ’s immune system was healthy, a full regimen of medications would improve it.

“Have you heard of HIV before?”

Biting her top lip, she shook her head, no.

Rakhmanina told her that ignorant people sometimes say bad things about those with HIV, and because of this, she shouldn’t tell friends she has it. The doctor quickly added that many patients still live normal lives: marriage, kids, good jobs.

Rakhmanina asked JJ whether she had questions, and she didn’t, so the doctor asked how she felt.

JJ stared at the wall and opened her mouth. For 14 seconds, no words came out.

“I feel okay,” she said at last.

Rakhmanina pressed for more. Sad? No. Scared? No. Happy to know? Yes. And would she tell anyone? No.

For another 20 minutes, the doctor explained to JJ that she was born with the virus, that it was not easily spread, that — again — some people are unkind to those who have it.

JJ laid her head on the exam table as the doctor told her to write down all of her questions in the coming weeks. Then Rakhmanina asked Lee whether she had any.

“I see she was paying attention,” her mother said. “So she understands.”

As Rakhmanina talked with Lee, JJ stood and picked up the pink bow, twisting it into her hair.

“I’m very proud of you,” the doctor told her before she left.

JJ sat next to her mother, spreading the hospital gown over them both. She played “Candy Crush” on her mom’s phone and rested her head on Lee’s shoulder.

“Did you understand?” she asked her daughter.

JJ nodded.

“You feeling okay?”

Another nod.

They waited in the room’s still fluorescence until JJ’s social worker and psychologist arrived. The pair asked about summer plans and congratulated her on making the honor roll. They gave her a plush pony.

Mother and daughter headed for the second floor, where JJ’s blood was drawn before she collected two “The Princess and the Frog” stickers for herself and a pair of “Frozen” stickers for her godmother’s daughters.

Back in their minivan, she stared out the window. Lee ran a hand over JJ’s arm as gospel played over the radio. “I turned it over to Jesus,” Lee whispered along with the lyrics, her daughter’s eyes closed. “I stopped worrying about it.”

They pulled into Checkers, and Lee picked up the loaded fries JJ had been so excited about that morning. At home, the girl sat at the living room table. She opened the box, then closed it, then pushed it away.

“Do you want to talk?” her mother asked.

“No.”

The afternoon waned. JJ sifted through homework then lay down on a fold-up bed against the living room wall.

“A lot done went through that little mind today,” Lee said. “She’s got to sort through it.”

Around 5, Lee told JJ to get ready to go to Nicole’s house for the night.

Tears fled down her cheeks. Her mother relented, hugging JJ and telling her she could stay.“I love you.”

JJ returned to the living room, where the lights were off and the blinds drawn. She played a computer game, scrolled through Instagram videos. She watched an episode of “SpongeBob.”

Her sister walked into the kitchen and asked how the appointment had gone.

“I don’t know,” JJ said.

Her sister left, and JJ turned off the computer. She lay back down on the fold-up bed, pulling a blanket over her head.

All that remained uncovered was the pink bow.

‘I’m nervous’

That night, JJ’s stomach hurt so much that Lee took her to an emergency clinic. A nurse practitioner who had worked with HIV-positive kids before asked what was wrong.

“I’m nervous,” JJ told her, “about what the doctor said.”

After the nurse reassured her, she ate three crackers and smiled again.

The next morning, before JJ got on the school bus, she neglected to remove her medical bracelet. “Are you sick?” a classmate asked. She refused to answer, then said almost nothing about her HIV in the days that followed.

And now, three weeks later, the girl with cornrows again walked across Children’s polished tile and into Room 3400.

She wore a denim purse, its strap running cross-body through the silver “Love” inscribed on her T-shirt. Tucked inside the bag was a wallet-sized Lisa Frank notebook with a multicolored front covered in dolphins and penguins. She had used it to record her thoughts, just as Rakhmanina told her to do.

Three questions were scribbled on the second page:

“What hospital was I born in?”

“Did I get my virus from my parents?”

“Why was I adopted?”

Chenere Evans, JJ’s psychologist, soon arrived. “You ready to work?” she asked.

JJ had never before practiced swallowing candies with a full understanding of why. Knowing, her doctors hoped, would make a difference.

“They’re so huge,” JJ said as she peered into the pill organizer’s 14 plastic containers, each side representing morning and night doses over seven days.

She started with a Certs cool mint drop. Deep breath, sip, mint, bigger sip, swallow.

She managed two more, then three Smarties.

“Next is Skittles,” Evans said.

After placing one on her tongue, JJ pressed both hands on the table and squinted at the ceiling. Three and a half minutes later, she sighed and dramatically laid her head down, as if collapsing at the end of a race.

“I’m glad you stuck with it,” Evans said.

“No more,” she said. “No more.”

One more, the psychologist pleaded and opened the organizer’s final compartment: “SAT PM.” Inside were Mike and Ikes, the largest candies Evans had but no bigger than the real medications JJ needed to take.

“It’s too big,” JJ said.

“You’re a pro at this,” Evans told her.

She slowly slid her limp hand across the table and picked a red. “If I can’t do it, I’m spitting it out.”

She sat up and opened her mouth. Water. Candy. More water. Again squinting, she crossed her arms and clenched her jaw. Just short of two minutes, JJ exhaled and pulled the candy out.

“It would not go down.”

Still, she had made progress. Both Evans and Lee congratulated her, and the psychologist asked what prize she wanted. JJ picked a bracelet-making kit.

Evans asked Lee if she’d had any concerns about the disclosure.

JJ seemed better, Lee said, but she hadn’t brought up the illness.

Her daughter poured the colorful rubber bands onto the table and acted as if she wasn’t listening. But JJ heard every word, interjecting when she wanted to: about her sister, her improved grades, her mom forgetting appointment times.

About her HIV and what it made her feel and think, though, she didn’t say a word.

“Mommy,” she interrupted once more, “I’m hungry.”

Evans gave JJ an organizer and a box of Mike and Ikes, and asked her to call the first time she swallowed one.

“I’m proud of you,” Lee told her.

“Are you proud of yourself?” Evans asked.

“Yes, ma’am,” JJ said.

She and her mother walked out of the office and onto the elevator. Still on her shoulder was the denim purse. Inside, the notebook remained unopened, and her questions remained unanswered.

Julie Tate contributed to this report.

Editor's Note: To protect her privacy, The Washington Post is identifying JJ only by her initials, and her mother and godmother by their middle names. With her mother’s permission, the Post followed JJ for five months and attended appointments she had with her doctors, therapist, psychiatrist, and psychologist. The staff at Children’s National Medical Center also gave The Post access to hundreds of medical records that detail a decade of JJ’s treatment.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments