Happy 60th birthday, NHS

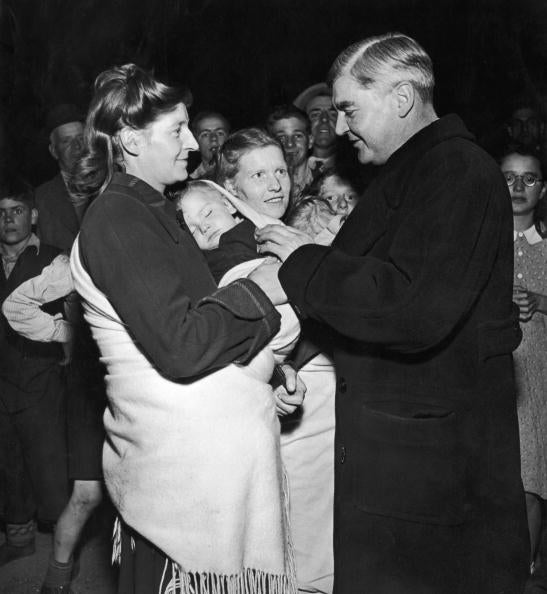

Aneurin Bevan's creation remains a vital part of British life after six decades. Ian Johnston reports

'Preventable pain is a blot on any society. Much sickness and often permanent disability arise from failure to take early action and this in its turn is due to high costs and the fear of the effects of heavy bills on the family." With these words, Aneurin Bevan, Labour's post-war health minister, spelt out the reasons why a National Health Service was necessary.

Amid opposition from the British Medical Association and the Conservatives, Bevan drove the NHS Bill through Parliament, finding support from nurses and doctors and buying consultants by "stuffing their mouths with gold".

The NHS was to prove an instant hit with the public. In 1946, when debated in Parliament, it had been thought the health service would cost £110m a year. The actual cost in the first year was more than double that and it has continued to rise ever since.

The growth alarmed politicians. In 1949/50, it cost the country some £305m (£7.8bn in today's money) and a spending cap was imposed. Even Bevan was taken aback, commenting: "I shudder to think of the ceaseless cascade of medicine which is pouring down British throats at this time."

New medicines and the advance of technology have since driven the cost of the NHS to more than 10 times the original. In 2007/08 nearly £90bn was spent on the service in England – an average lifetime cost of £134,895 per person. Despite the cost, complaints and and controversies, it remains one of Britain's most popular institutions.

NHS historian Geoffrey Rivett said patients today receive much better treatment, but with "less respect and less grace" compared to the early days because of the demands placed on staff. "If you were a patient in 1948, you expected very little of the system and were amazingly pleased if you got much at all," he said. "Now we are in a consumer society and we expect a great deal."

1940s

Edna Adams, 79, of Cowbridge, South Wales, was admitted to St David's Hospital, Cardiff, days before the creation of the NHS on 5 July 1948. Her daughter Pamela was born on 11 July.

"I was in hospital on 30 June 1948, and the National Health Service came in on 5 July. I paid four guineas (£4.20) for the bed for a fortnight's stay in hospital. In those days it was a fortnight to have a baby and you were in bed for 10 days. I was given about three guineas back because of the NHS. I was elated because that was about a week's wages. If you went into hospital before the NHS, it was the almoner who decided what you would pay. It was free if you could not afford it, but you had to prove it.

"I am in and out of hospital a great deal now and I think the NHS has become too big for itself. I don't know how it is managed. It seems to be so out of control. There's all this new technology. There was none when I was a girl; you either lived or you died. But I have nothing but praise for our service. It is oversubscribed in many ways, but I couldn't fault it."

1950s

Leo Redpath, 62, of Longridge, Preston, contracted polio as a child and stayed in the Ethel Hedley Orthopedic Hospital, near Ambleside in the Lake District, where he had several operations in the 1950s.

"It was a veterans' hospital converted into a hospital for crippled children – that was the language used then. I have mixed feelings about it. A lot of what was done was for our care, but today we'd find it quite astonishing. We were allowed one visit a month from our parents. The rationale was 'the kids are always upset after visiting time'.

"The matron was definitely the boss. There was also a ward sister called 'Battle Axe Bertram'; she was very, very strict. Your beds weren't allowed to be untidy. Everyone was pushed outside on to the veranda – plenty of fresh air and all that. In pre-NHS days, people with disabilities tended to be shoved away in a corner somewhere. Now there are far more disabled toilets and all modern buildings have access ramps.

"In those days the consultant was king. They would come swanning in with an entourage respectfully trailing behind him."

1960s

Tena Roberts, 52, from near Market Drayton, Shropshire, was diagnosed asthmatic aged four. For the next 10 years, the condition blighted her existence until she was prescribed a drug that changed her life.

"I remember one elderly GP telling me to 'pull my socks up and stop coughing, stop being so silly, I could stop if I wanted to'. But I couldn't and I remember telling Mum I couldn't stop. She's asthmatic as well so I think she knew I wasn't faking it.

"As I got older my asthma got worse. I had recurrent attacks and it was frightening because I couldn't breathe. The GP would prescribe tablets and, after a few days, I would recover – to a degree.

"We went to Australia in 1966, and when I returned in 1970, I was quite bad. I'd lost weight and was very thin. I was eventually referred to hospital. They treated me with a brilliant new drug called Intal. For me, it was like a miracle. It completely turned my life. From being a sickly, thin child, I became distinctly robust and energetic. The NHS tries to provide the best for everybody, but I don't think they manage that all the time."

1970s

Rachel Jelbert, 37, of Edingworth, Somerset, was four years old when surgeons operated to correct a congenital heart condition which severely restricted oxygen levels in her blood.

"When I was born in 1971, they discovered I wasn't very well and I was transferred to the Royal Brompton Hospital in London the day after. My mum had no idea – there wasn't any ultrasound. Nowadays they can detect things so they are prepared. It was in 1975 that the actual switch operation was done. At the Brompton, they had the old-fashioned Nightingale-style wards and I remember liking the nurses' uniforms.

"I can picture the ward and the nurses looking after me, being in a room with my mother asleep on a mattress. The care was very good and it inspired me to train to be a nurse. It's hard to imagine not having the NHS because it's been there since I was born.

"At the time, they weren't sure if I would survive. The survival rate was not good. They implied I might live to 15 or, if lucky, 21. I'm now 37."

1980s

Marc Thompson, 38, of south London, was told he had tested positive for HIV, aged 17, at Westminster Hospital.

"I wasn't ill, but in December 1986 I decided to go for a test which had only been around for a year or less. I was completely convinced, only having had a couple of sexual partners, that it would be negative. The result took about 10 days to two weeks. I think I remember getting a bit of pre-test counselling, but I was very young and my whole idea was 'it's going to be negative'. I was called in, saw the doctor, was sat down and told in very, very plain terms my result had come back positive.

"I was fortunate because they handled it in a dignified and supportive manner. Given the climate in the 1980s, that was really beneficial and useful. There were some real champions within the NHS whom we should be celebrating. This was something the NHS probably hadn't faced before and it responded admirably. Today, things have really moved on. Staff are welcoming and don't make you feel like a pariah. The NHS and its staff have been really key in convincing people not to be ashamed of living with HIV."

1990s

Sara Dignam, 41, an accountant in Milton Keynes, woke up feeling 'a bit fluey' in January 1990. Her life was saved when her GP realised she had meningitis.

"They didn't think I would pull through. I was in intensive care for 12 weeks and on life support for about five weeks. They induce a coma so they can work on you. They were supporting my body, all my functions, and I had about 100-plus blood transfusions. I had lots of internal damage; parts of my fingers and toes were amputated and I had skin grafts on my knees. I had to learn to talk again because I had a tracheostomy. I couldn't walk and had to have physiotherapy. I had to learn to use my hands again. I looked like something from Belsen, really thin and yellow because I'd had liver and kidney failure.

"If you are really ill you cannot fault the NHS. If you really needed them, even now, they would pull you through and think about the cost afterwards. I think we are so lucky.

"If somebody complains about the NHS, I find it very difficult because, when you need them, there is nowhere in the world that supports you like the NHS."

2000s

Debbie Hirst, 57, a former pub landlady, of St Ives, Cornwall, was diagnosed with terminal cancer in 2004. She was told she had three months to live, that a drug called Avastin could prolong her life but the NHS wouldn't pay. She was told if she personally contributed £60,000 she could have it but then came a further cruel twist.

"We put the house on the market and started saving like crazy. Then I was told they had changed the policy and we were no longer allowed to do it. We took legal action and got publicity. After the cancer spread and my oncologist said Avastin was the best treatment, I began to get it. After the first four treatments the tumour shrank 50 per cent. I would not be here now but for Avastin. Once it stops holding it, that's me gone.

"I'm so, so grateful for the health service; the people who deal with me are brilliant at what they do. I believe strongly in the NHS and I believe everything Aneurin Bevan said. If you have got an illness, we should help you, make you better. It shouldn't be a matter of funding; that's totally wrong. If I was given Avastin, why aren't others?"

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies