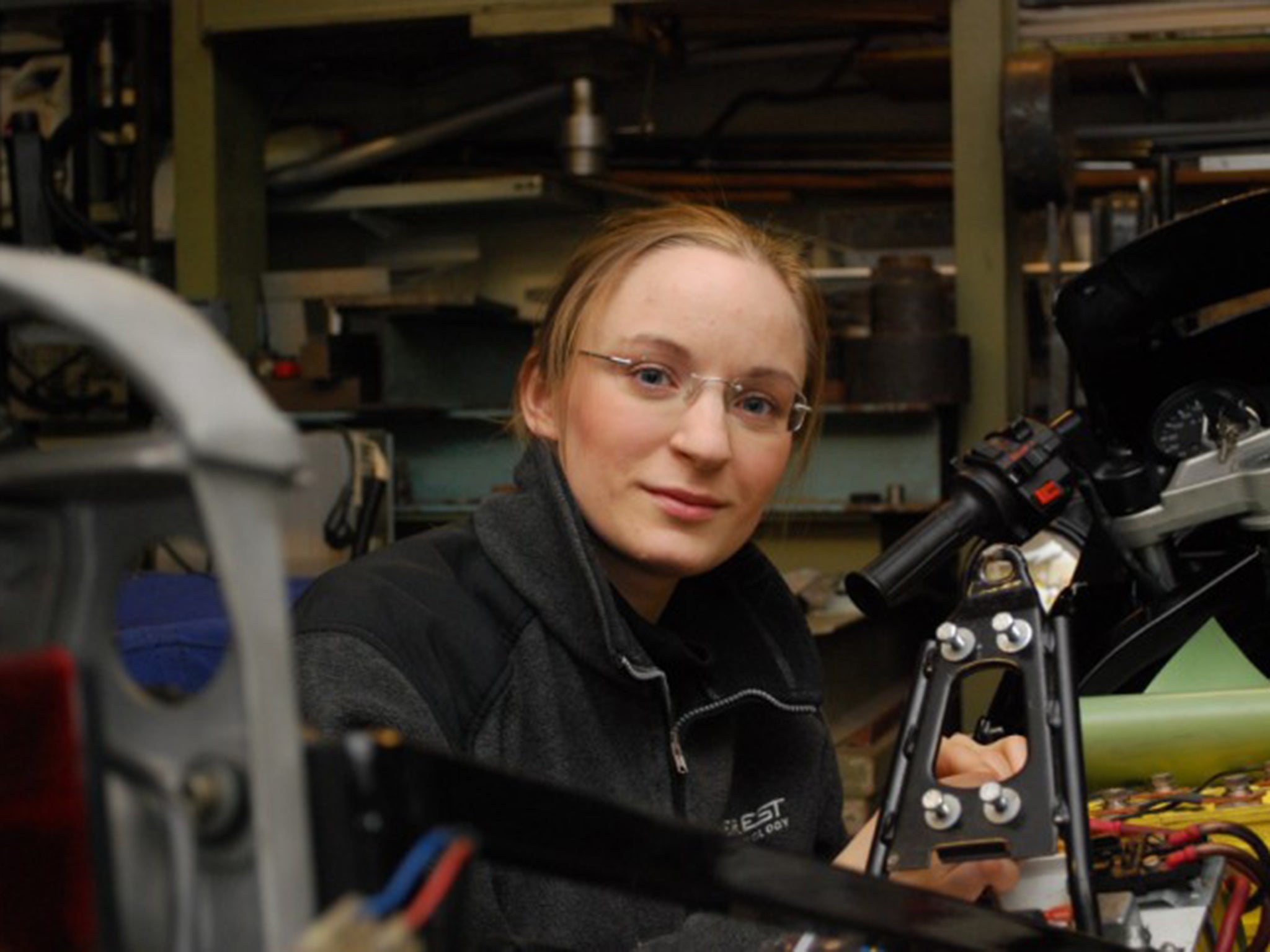

World's fastest female motorcyclist Eva Håkansson: 'I'm on a quest for 300mph'

'It’s not the speed that gives me the thrill - it's the joy of doing something that no one has ever done before'

Eva Håkansson is the world’s fastest female motorcycle rider, but the 34-year-old Swede isn’t resting on her laurels. “My goal is always to be faster,” she tells The Independent. “I’m on the quest for 300mph, but many things can go wrong.”

Håkansson earned her current title on Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats in September last year, when KillaJoule – an electric cycle she designed and built herself – reached 241.9mph in the official race on the densely packed salt pan.

The US-based mechanical engineer was hoping to hit 300mph in KillaJoule this weekend, but flooding on the flats forced the cancellation of racing. Her next opportunity to write herself into the record books will take place between 12 and 16 October at an event called the Bonneville Shootout.

The KillaJoule, a bright red, cigar-shaped projectile, has had a number of modifications since last year’s run. “It’s always a work in progress so there are some upgrades in horsepower and there is less drag,” explains the University of Denver PhD student. “All that makes the computer say that it will go 300mph.”

Håkansson appears to inhabit a glamorous world, an image confirmed by her appearance in the latest ad campaign for Johnnie Walker, alongside racing driver Jenson Button and actor Jude Law. But she insists “it’s not the speed that gives me the thrill”; rather it’s “the joy of doing something that no one has ever done before”.

The real pleasure comes from the 360 days she spends building high-speed vehicles in her garage; the five days of racing are “mostly quite stressful as that is when you prove your work”.

Håkansson has two main reasons for breaking speed records in an electric vehicle. First, to show that women make as good engineers as men and, secondly, to change the perceptions of eco-friendly vehicles. She describes her record attempts as “eco-activism in disguise”.

“The general perception of anything that is eco-friendly and low emission is that it is really boring and you wouldn’t want an electric car,” she says. “My mission is to change that perception by showing that electric vehicles can be insanely fast.”

Electric cars would fulfil the needs of “about 95 per cent” of the population, she adds. “I don’t think we will see electric long-haul trucks or electric commercial airplanes in a long time, but for daily driving electric cars are outstanding”.

Håkansson and her husband, fellow engineer Bill Dube, get around in an electric car powered by solar panels on the roof. “It costs us practically nothing to drive and it’s running on sunshine.”

She is due to finish her PhD in about six months, at which point she hopes to convert her “high-end hobby” into a full-time career.

In the US, and also in the UK, where only 6 per cent of women are engineers, “many people seem to think that some unknown, unfathomable force makes us unable to be engineers. I want to change that perception, because women make excellent engineers and little girls and older girls and women need to see that the tech sector is an excellent career choice.”

She believes women may be put off Stem (science, technology, engineering and maths) careers “because they think they can’t do it because they have been told all their lives that engineering is just for boys, and people accept that as some kind of undeniable fact”.

Engineering runs in her family. Her father, Sven, was a Swedish road racing champion in the Sixties, who built and tuned his own machines. He also took a keen interest in electric-powered vehicles, developing Sweden’s first electric street-legal motorcycle, the ElectroCat, with Eva.

Håkansson’s mother was also an engineer – “the only female in her class” – as are her brothers. “Looking back at my childhood I realised I never really played with things. I was just always building things. I thought that was completely normal. I learned how to use a sewing machine when I was four. It wasn’t until I reached my twenties and thirties that I realised how unusual that was, and what a great education I’d had. All the foundation for my technical work comes from my childhood.”

She describes the moment of setting a record as “like a great plan coming together, a feeling that you pulled it off”.

But the run itself is a “strange mix of boredom, terror and magic”, she says. “When you surpass your record, suddenly you are in uncharted territory. You’ve never been this fast. Your bike has never been this fast and you just don’t know if it’s going to break or list or crash, and also it’s very claustrophobic. You are inside a little tube, a straitjacket, and it’s also very hot. You are in the middle of the desert. I have a speedometer, so I know how fast I am going and it is almost magic when it works. The world stops and afterwards there’s a big release.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments