Three years ago George Osborne held out the prospect of a “march of the makers”. But all we have heard, so far, is the pitter-patter of tiny feet. Manufacturing output has grown by around 5 per cent since early 2013. But the sector has not been driving the recovery. In the second quarter of 2014, GDP was 3.2 per cent higher than a year earlier. Services accounted for 80 per cent of that expansion. Manufacturing’s contribution was less than 13 per cent.

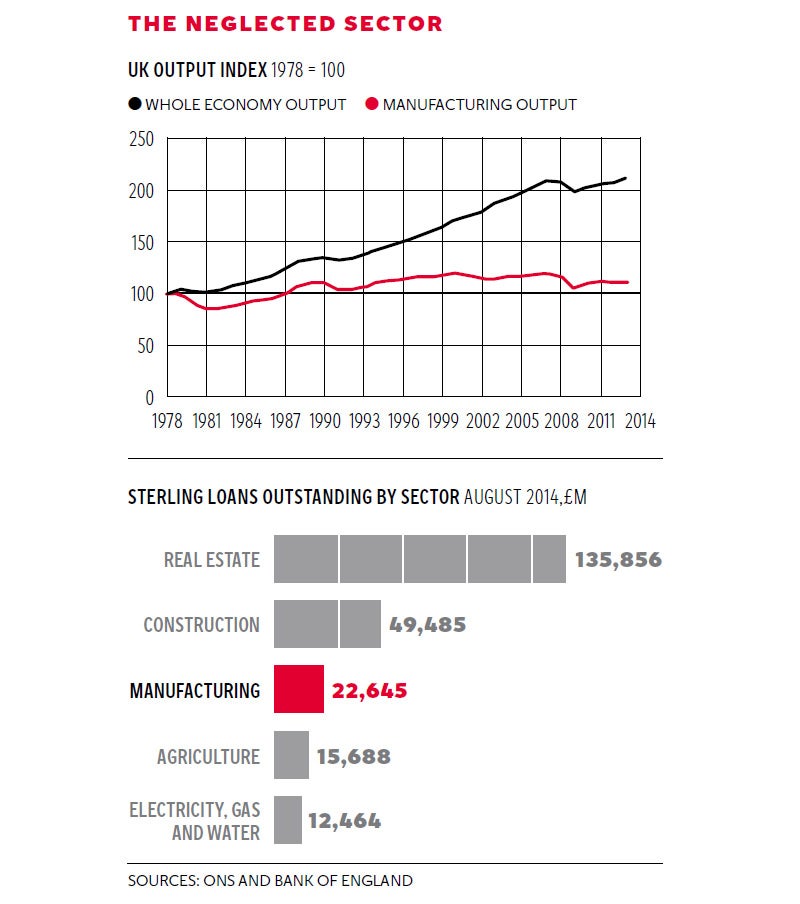

Moreover, the level of manufacturing output remains 5 per cent below where it was way back in 2008: that’s six years of depression for the sector. In a longer context, the picture is even more depressing. As the first chart shows, while the overall economy has grown by around 111 per cent since the late 1970s, manufacturing output is up by just 10 per cent.

Manufacturing, as the Office for National Statistics (ONS) reminded us yesterday in a review of the sector, still makes a significant contribution to the British economy. It’s only a 10th of output (down from 36 per cent in 1948) but accounts for half of all our exports. Manufacturing also pays good wages relative to services, reflecting the higher added value nature of its activities and the healthy productivity of the sector. At a time of falling real wages its support has been invaluable for millions of families. Manufacturing dominates our research base, which is so vital to our future prosperity, with firms in the sector accounting for 70 per cent of private research and development spending.

The idea, sometimes put forward, that we can afford to forget about old-fashioned manufacturing industries and focus instead on sexy internet start-ups and the lucrative activities of the City of London, withers under closer scrutiny.

Yet what the ONS research inadvertently underlines is just how much we have lost as a result of the relative decline of the manufacturing sector over the past three decades. If manufacturing delivers all these good things both for the economy and living standards, as it does, we should desire much more of it.

The ONS paper does not go into the causes behind the declining share of manufacturing in both GDP and employment, but they are worth examining. The relative strength of the pound over much of the past 30 years has been a major drag on the competitiveness of our manufacturing exporters, as the economist John Mills has long pointed out.

Sterling has been driven up by the explosive growth of financial services, which stokes demand for our currency. A strong pound helps financiers, but hurts our manufacturers. The Bank of England and the Treasury have been guilty of ignoring the plight of the latter in the past.

More recently the manufacturing sector has been hit by a very large demand shortfall. The shortfall is partly a result of the weakness in our major export markets in Europe. But the Government’s domestic demand-dampening fiscal austerity programme did not help. We are also reaping the consequences of historic neglect. In recent years some advanced economies, notably Germany, have benefited handsomely from the growth in demand for capital goods from emerging markets such as China. We missed out because we never built a strong presence in those sectors.

There remains a drought of bank finance for manufacturers in Britain relative to our peer economies. As the former chair of the Financial Services Authority, Adair Turner, notes, our banks simply do not perform the function, described in economics text books, of lending to industrial firms to invest in new capital machinery. The latest Bank of England figures show that the stock of loans from the UK banking sector to manufacturing firms is currently just £22bn. As the second chart shows UK banks have lent six times more to property development companies. Loan demand is now weak, suggesting that manufacturing firms have largely given up on the big banks.

That lack of credit helps to explain why the UK’s investment rate, as a share of GDP, is lower than the OECD average. It also helps to explain why Britain’s research spending is lower than in most of our peer economies.

The Chancellor was right when he said we need a manufacturing resurgence in Britain to power growth, rebalance the economy and close the chronic current account deficit. The problem is that he has cooled on that agenda, deciding instead to pull the lever of easier housing purchase finance in order to get economic activity up. We’ve seen how this movie ends before and it’s not pretty.

What would a serious policy of support for manufacturing look like? It would entail a structural overhaul of the banking sector, including the establishment of a publicly owned bank with a specific remit of funding small firms. It would entail a holistic industrial policy, with firms incentivised into increasing investment in new plant, spending more on research and training staff. It would mean ministers devoting their full attention to these challenges, rather than lobbying against EU caps on bankers’ bonuses. It would not, by the way, mean pulling up the British drawbridge. The ONS research makes it clear that foreign investment has helped productivity growth. We should welcome more.

At the moment, despite the best efforts of the Business Secretary, Vince Cable, we are still some way from getting this right and giving Britain’s manufacturers the tailwind they need. And that means the long wait for the triumphant march of our makers is likely to stretch on.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies