Hamish McRae: A world that is now divided into the haves and the have-debts

Economic Life: The sorting out that results from the debt load has hardly begun and will be a lasting legacy of this cycle

The world is dividing the cash-rich and the debt-heavy – the "haves" and the "have debts" so to speak. This always happens to some extent as economies emerge from a downturn but the severe damage to the banking system and the low-inflation environment has made the distinction much sharper than in previous cycles.

Reading through the Bank of England's latest Inflation Report, one of the things that stands out is the extent to which the UK will be held back by the combination of its debt load and its fiscal position. Meanwhile the developed world as a whole is being held back by debts, while the emerging nations are racing ahead.

But this is not just a macro-economic matter. It is a corporate matter, for companies that are heavily indebted are having to sell assets, while cash-rich ones can snap them up. It is a banking matter, for look at the chasm that has opened up in British banking between the two successful banks, HSBC and Barclays, and the two bailed out by the government, Royal Bank of Scotland and Lloyds/HBOS. It is a government matter, for countries with massive national debts are in a quite different position from those with sovereign wealth funds. It happens at a personal level between families that have spare cash and can negotiate prices down for things they want to buy, and families that need to sell assets, including sadly sometimes their homes. And it is a resource matter, for given the general squeeze on energy supplies and raw materials worldwide, countries that are resource-rich seem likely to emerge from recession more strongly than those that are resource-poor.

All this might seem self-evident enough, but because the adjustment has yet to begin I don't think that we fully appreciate how important the distinction will be; it will hang over the world for the next decade, maybe longer. Here is some structure to help think about it. There are, I suggest, at least half-a-dozen areas where the cash-rich (or resource-rich) are likely to streak ahead.

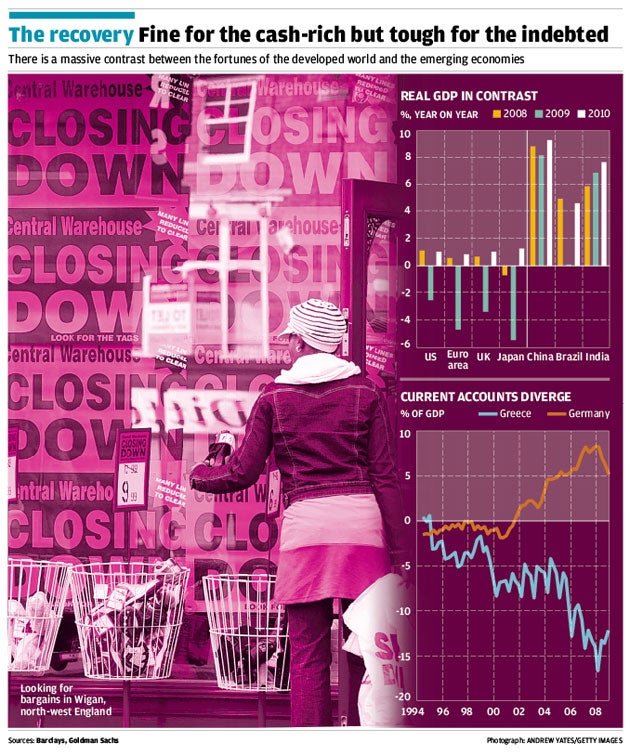

The most obvious is the distinction between the major developed economies and the major emerging ones. The main graph shows some new forecasts from Barclays that bring this out. The divergence is stunning. Indebtedness is not the only factor holding the developed world back, but it is a material one. Note that the most indebted country in the world, Japan, has also been the slowest-growing for the past 15 years. And of course slow growth or worse, no growth, makes it much harder to reduce indebtedness. Japan has totally failed to do so, and is currently most concerned about a modest rise in interest rates and the implications for debt service costs. We in the UK should be concerned too.

The next distinction is within Europe. There is a widely-appreciated divergence on the fiscal side and high-deficit countries, such as Greece, will be under great pressure to get that under control. Much less noticed has been the divergence on current account within the eurozone, and I was struck by the contrast between the great export powerhouse of Germany and the yawning current account deficit of Greece, a contrast evident in the bottom graph. In 2000, when the euro was an infant, the current accounts were in much the same position, with small deficits. Since then ... well, you can see what has happened.

In the corporate world there has been a savage sorting out of winners and losers. It is too big an area to be able to say much that is helpful in a short paragraph, but I suppose the big point is that recession speeds up changes that would have taken place anyway. So, to take just one industry, this year China has become the world's largest car manufacturer, some three or four years earlier than people were predicting even two years ago. We have Toyota becoming the world's largest motor company, and making money at it, and we have General Motors in intensive care. Less noticed, while GM is struggling, Ford with its stronger finances has options that GM does not have. Meanwhile India's Tata may emerge from the downturn as a material competitor against the Japanese and Chinese industries – though that is not yet clear.

On the resource-rich/resource-poor axis there is the obvious distinction noted above, but it is worth making the further point that as recovery picks up, driven by the emerging world, we are going to get an increase in raw material and energy prices even when demand in the developed world remains slack. That is happening now to the oil price, a marked contrast to other recoveries when it took several years of growth before rising output in the developed world began to pull up raw material prices. Result: another thing that will slow the recovery for most of the developed world.

There is not much to be added to the individual and family distinctions except perhaps to point out that access to credit has changed radically, self-evidently in the mortgage market but also in credit cards and other forms of consumer lending.

When credit was easy there was no huge advantage in having spare cash. Power was with the seller. Now with the plethora of closing-down sales and traders prepared to do deals for cash, power is with the buyer. Credit conditions will become easier, but for a decade at least, the financial services industry is going to be very cautious.

Finally, some thoughts about the rebalancing that is taking place within developed world economies. Focusing on the UK, during previous economic downturns there was a much sharper decline in manufacturing output than in service industry output. In other words manufacturing bore the brunt of the pain.

This time around the pain has been much more widely spread. The fall in manufacturing has been steeper than that in service output, but not on the scale it was during the 1980s. Meanwhile the public sector has been protected, even expanded, while the private sector as taken the hit. From now on, however, the big decline seems likely to take place in the public sector. So we will have some sort of gradual expansion in the private sector but several years of contraction in the public sector. That sort of divergence will be greater than at any time since post-war disarmament in the late 1940s, and is a direct result of the massive rise in the indebtedness of the public sector.

All this will give a different tone to this expansion – the growth phase that has just about started now but is by no means yet secure. There are several ways in which the current downturn has been less damaging than previous ones.

Mercifully we seem unlikely to return to the levels of unemploy- ment of the early 1980s and early 1990s, and it was really interesting to see that total employment, albeit allowing for part-timers, has started to rise. But the sorting out that results from the debt load has hardly begun and will be a lasting – and difficult – legacy of this cycle.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies