Hamish McRae: America isn't working and the rest of the world should be alarmed

Economic Life: There are deep-seated concerns that the US workforce has too long a tail of less-skilled people doing jobs that can be done abroad by workers on lower wages

The "jobless recovery" has become a catchphrase to describe what is happening in the US, and could also be applied to Continental Europe. In recent months, employment in the US has inched up, despite what seemed at least to be decent growth, while (and this has really shocked me) the eurozone has created no net new jobs at all in the past three months. The UK has at least managed to create 300,000 over this period.

In a way the failure of the US to generate jobs is even more worrying than that of Europe. Levels of unemployment are broadly similar at 10 per cent. But Europe does at least have the "excuse", if that is the right word, of a relatively inflexible labour market. Employers in Europe can be expected to be reluctant to take on new labour as demand rises because they are not able to shed that labour if the rise in demand falters. But in the US there are fewer such inhibitions, or at least there should be. Yet the rise in employment this cycle has been the lowest since the Second World War. As a result unemployment has remained stubbornly high. Why?

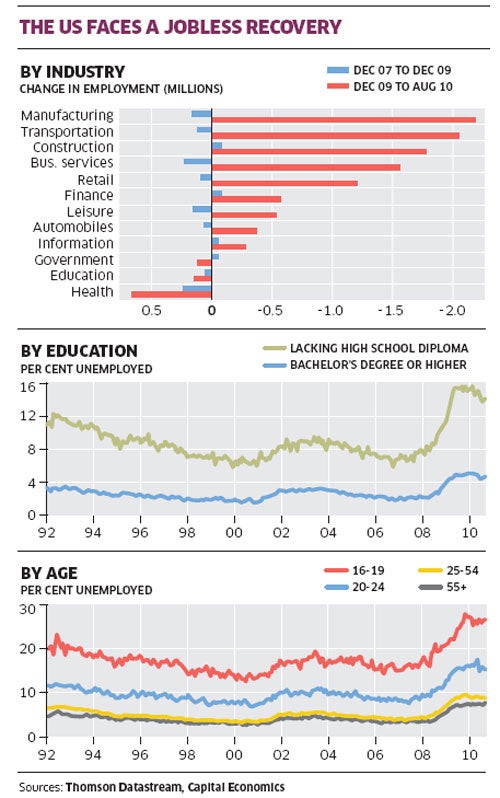

The answer is complex, so we should be suspicious of pat responses, but it is clear that there are several forces at work. One is simply that the sectors that have shed most labour are in no shape to rehire. The main losses during the downturn were manufacturing, transport and construction, three industries that have been particularly savaged by the recession, as the top graph, above, shows.

Since the recovery began nothing much has happened in terms of additional employment in any industry, whereas in previous recoveries even the construction industries were busy rehiring.

But it is not just that. There are deep-seated concerns that the US workforce has too long a tail of less-skilled people doing jobs that can be done abroad by workers on lower wages. One aspect of American genius is the way it can train low-skilled workers so that they can deliver high-quality services, and there are some jobs, for example in the hospitality trades, that cannot by their very nature be exported to China or India. But this time the premium on education seems to have widened, as the next graph shows.

If you have a degree you are unlikely to be unemployed, even through this difficult cycle. If, on the other hand, you did not even graduate from high school, while you were always vulnerable, this downturn has been a catastrophe far beyond all the experience of the past 20 years.

Capital Economics, which pulled together this data, also notes that there is a mismatch of skills. There are relatively few people with the skills to fill the posts in the growth sectors of healthcare and education and too many with the skills in construction, competing for the few jobs there.

The young have also been disproportionately damaged by this cycle, as the third graph shows. The older you are the less likely you are to be unemployed but this cycle. But while unemployment rates have risen for all, the position of the 16 to 19-year-olds, who, of course, also do not have university degrees, has been a disaster. The world is not fair in America or anywhere else, but the US labour market has become particularly unfair to young job-seekers.

So, what are the implications of all this? There are obvious things that can and will have to be done. The US already has quite high enrolment in higher education and just nudging that up further will nibble away at the skills gap. There are specific skill shortages where the market may not be training sufficient people. The need for employers to provide healthcare, and the soaring costs of that, may inhibit hiring, particularly by small- and medium-sized enterprises.

But there is a wider concern here. It is that the fundamental features that have made the US economy so competitive may be waning, or at least be less relevant in our ever more global world economy.

There is something of a crisis of confidence in the US at the moment about its economic system. President Obama appears unable to frame effective policies to revive the economy and there are fears of a double-dip recession. The present speculation about the possibility of some further stimulus reflects these concerns, though anyone arguing that the government should run a greater budget deficit has to answer the basic question: if a 10 per cent of GDP deficit does not boost the economy, why should a 12 per cent one be expected to do so?

Alongside this short-term cyclical concern comes the longer-term one. Americans can see that their economy has lost ground to the emerging economies as a result of the cycle. That is understandable. But even more alarming is the possibility, probability or threat, call it what you will, that the US economy is in long-term structural decline. Its less-skilled workers are being undercut by cheaper labour in Mexico and in Asia. Its high-skilled ones are having their ideas stolen by companies in the emerging economies that copy US products or pirate US software. The argument is that the US is being treated unfairly in world trade: it plays by the rules but the new booming economies of Asia don't.

This is partly about China's currency policy – have you noticed in the past few weeks China has allowed some appreciation of the yuan, presumably in an effort to head off Congressional pressures for trade sanctions? But it is not only about that; it is also a more general resentment towards the US business establishment.

US companies are profitable at the moment, in the sense that corporate earnings are close to a record as a percentage of GDP. So why are they still sending jobs abroad and shutting down US plants? Add in the fact that middle-income Americans have seen, on average, hardly any increase in living standards over the past generation and you have a deep discontent that extremist politicians can tap into. It seems to me to be monstrously unfair for the US electorate to blame the present administration for problems that did not occur on its watch but were entirely bequeathed by the previous one. But the lacklustre recovery reflects a lack of confidence in economic management and that lack of confidence has become self-reinforcing, as the weak job market shows.

I am not sure where this ends. The balance of probability surely is that the world has entered a growth phase that will last several years. We will have some sort of relapse in the next few months, for this frequently happens, but in another two years' time growth will have returned, not just for the US but for the world economy as a whole. But if it is a jobless recovery and unemployment is still close to present levels, then the long-standing dangers of protectionism will become harder to resist. The bottom line is that American unemployment is a profound worry for Americans but it is, or at least should be, a profound worry for the rest of us, too.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments