Hamish McRae: Europe is still searching for stability and the UK must find it too

Economic Life: At best we will have a sullen calm; at worst, a further crisis engulfing several of the weaker countries and unfortunately probably also their banks

How do youachieve financial stability? Or, put another way, does the greatest threat to stability come from failures by the banking system or from poor monetary and fiscal management by countries?

This is really the central issue that the Bank of England's new Financial Stability Report, published today, confronts. When these twice-yearly reports were started the idea was they should identify what the banks were doing wrong and the risks associated with that. But now we know more or less what they did wrong – bad conventional lending, mostly on property, and buying complicated products that mis-priced the risks involved – and we know more or less the scale of their exposure.

What we don't know is whether the weaker European countries will be able to repay their debts as they fall due and whether the currency in which they have borrowed, the euro, will itself survive. Sovereign default has arguably become a greater threat than banking default. True, the two are linked, for were some of the weak eurozone countries to default that would put great pressure on banks that held that debt. And it is the weakness of the Irish banks that eventually bumped the country into seeking a bailout from Europe and the IMF. But intellectually the two are different. One results from a failure of commercial judgment, the other of political self-discipline.

Step back a bit. On a long historical perspective there is still great faith in the ability of most major economies not just to service their national debt, but also to repay debt without debasing its value by generating massive inflation.

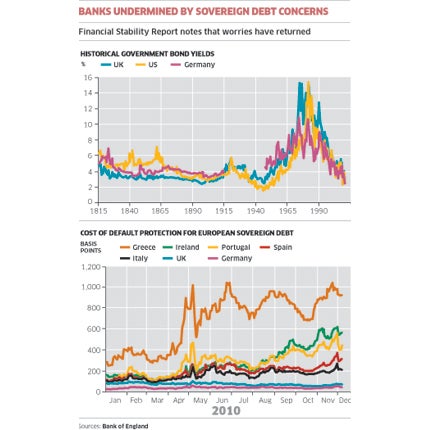

If you take the nominal interest rates on British, German and US government debt as a proxy for faith in their financial and economic policies, you can see that the great crisis came in the 1970s and 1980s. The first graph, taken from the report, shows yields on these bonds since 1815, with a bit of a break between 1915 and 1946 for Germany, when data was confused.

As you can see, with that exception, the three countries managed to come through the first 150 years of this period without a disastrous loss of confidence in their finances. They came through world wars, the American Civil War, all the stresses of industrialisation and so on, yet the thing that destroyed confidence was the great inflation of the 1970s and 1980s.

Now, thanks to anti-inflationary policies gradually pieced together from the late 1970s onwards, these three countries (and many other developed economies) have benefited from the sustained fall in interest rates that carried right through to this year. In the past couple of weeks there has been some rise in rates. One explanation is there are growing fears the US in particular will try and inflate its way out of its debts and therefore the markets are demanding higher interest rates to compensate. The other is that the growth in the US is now more secure so naturally there will be some rise in longer-term interest rates as demand for finance increases. But, and this is the main point, general overall faith in these three governments' debt has been retained.

Unfortunately, this is not the case among the weaker eurozone countries. The second graph shows how the cost of insurance against default for different countries has risen over the past year. The cost for the UK and Germany remains very low (and the gap between the two has narrowed since the Coalition came to power) but for Greece it is roughly 1,000 basis points, or 10 per cent, while for Ireland and Portugal it is between 4 and 6 per cent. The point here is that with premiums at this level, the bond markets are closed to these countries. The markets are saying there is a very good chance they will not be able to repay the debts as they fall due.

But suppose banks hold this sovereign debt and need to raise cash against these holdings. They can take the debt to the European Central Bank and use sovereign bonds as a pledge to raise liquidity. But that transfers the risk to the ECB.

Well, yesterday the ECB nearly doubled its own nominal capital, a move that is seen as reflecting its fears it might indeed face losses on its holdings of sovereign debt. It did not say that, of course, referring instead to volatility in foreign exchange rates, the gold price and the like, but then the ECB could hardly say that it expected a Eurozone country to default, could it?

So what can be done? The EU leaders were meeting yesterday and today to discuss the idea of a "permanent crisis mechanism" to make sure Eurozone countries follow sound financial policies and are supported collectively by the other Eurozone members as they do so. The idea is this will replace the present emergency support fund – the one that has so far bailed out Greece and Ireland – after 2013. But it is hard to see quite what form this will take, as it goes to the heart of the problem: to what extent do the solvent Eurozone countries, most notably Germany, have to take responsibility for the debts of the less solvent?

It may be that the markets will calm down as growth resumes in even the weaker eurozone countries. Ireland has had a decent third quarter of growth, driven mainly by exports, which is encouraging. But the general perception seems to be that Spain, Portugal and Italy will all struggle to generate much growth in the coming three or four years and they all have to go to the markets to roll over the public debt, as well as financing their fiscal deficits.

At best we will have a sullen calm; at worst, a further crisis engulfing several of the weaker countries and unfortunately probably also their banks. As the Bank of England points out today, the UK is only partially insulated from what is happening on the periphery of the eurozone, given the interconnectedness of the financial system and the importance of stability in financial markets.

The report also warns, albeit obliquely, that the present very low bond yields may be coming to an end. It notes lenders are seeking higher returns on their funds and warns that if longer-term rates climb this will put pressure on borrowers, including households, companies and countries.

Low yields may be "masking latent distress". Or, to put the point in UK domestic terms, there may be a lot of people who can manage to service their mortgages at present low rates but who would struggle to do so were rates to hit normal levels.

My own feeling, for what it is worth, is that banking weakness is not now the prime problem. As growth picks up, asset prices will rise and most banks will be able to work through their bad debts. Even distressed debt is usually worth something, even if it is only 20 per cent or 30 per cent of its face value. And thanks to the huge gap between lending rates and the cost of deposits, most banks are making good running profits. The problem is sovereign debt and that burden will, I am afraid, remain.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments