Hamish McRae: Tech revolution will run and run – but where to next is the question

Economic View

A holiday weekend and a chance for reflection on what really changes our lives and what merely trims it at the edges. Those of us who write about economics inevitably focus on what is happening to the economy: whether it is growing, what is happening to jobs, interest rates, inflation and all that. However, there is another side to our economic life which is just as important, maybe more so, and that is the way in which technology alters just about everything.

It changes our jobs in two ways: what we do and how we do it. It changes relative prices, making some things such as medical care more expensive (because it is better) and other things, such as phone calls, cheaper. Over time, it improves our living standards, because it is the key element in lifting productivity, something that will be a huge challenge for all advanced economies in the future.

There is a very big question here, which is whether it will be possible to improve living standards as swiftly in the future as they have grown in the past. More of that in a moment. First, some thoughts about which technologies will really change things and which will have only marginal impact – thoughts provoked by a new study by McKinsey's research arm, McKinsey Global Institute, called Disruptive Technologies: Advances that will Transform Life, Business and the Global Economy. This looks at 12 such technologies and tries to predict the gains these will bring to the world economy to 2025.

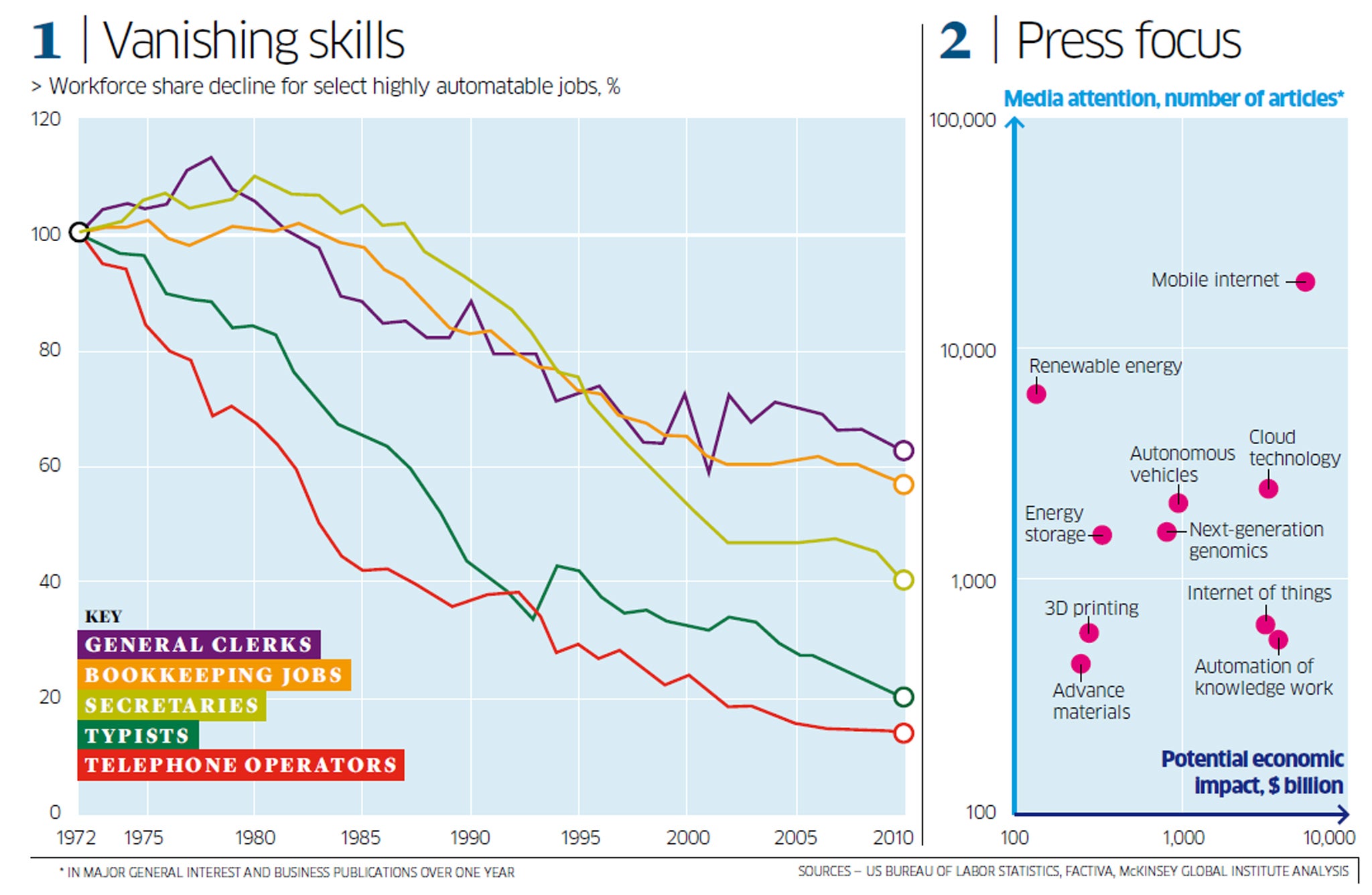

First, a look backwards. The main graph shows how some types of job have over the past 40 years been almost completely automated away. The most extreme examples are typists and telephone operators, for we all do our own typing now and connect our own calls. One of the astounding social changes has been the near-demise of the fixed-line phone as a way of contacting each other – a change that has its downsides as well as upsides. Many such changes are a result of the development of the internet and associated technologies, but note that the decline in both those types of job was well under way by the time that the net took off in the middle 1990s.

Now flip this forward, for under the head of "automation of knowledge work", the increases in productivity that can be obtained in the future by automating what was previously done by human beings, is one of the main categories of advance. For example, by 2025 what we think of as a doctor's appointment might be entirely automated, with a sensor feeding information about our day-to-day health to a computer, which would then advise on the appropriate treatment or call in a human doctor if that were necessary.

Other categories of activity where technology can be expected to transform our lives include some obvious ones, such as mobile telephony and energy storage, some that have received a lot of publicity such as printing and renewable energy, and some that seem to have been around a lot time but have not developed in quite the way predicted, such as robotics.

One striking thing is that the amount of publicity given to technologies does not square with their potential benefits as assessed by McKinsey. The right-hand graph shows the numbers of relevant articles on a number of these technologies on the vertical axis and the potential benefits on the horizontal one.

Top of both lists comes the mobile internet, as you might expect, but the automation of knowledge work and the internet of things attract much less attention, yet have almost as great potential benefits. The first of these two are obvious enough but, for me, the internet of things was a new one. What it means is getting machines that are connected to the net to communicate with each other without human intervention: sensors that track performance or location, transmitting that information to other sensors that then change what another object is doing. We use it at the moment in supply chains and in power grid management, but it is a revolution that has barely begun.

By contrast, we read a huge amount about renewable energy but the potential benefits might bring are relatively small. Advanced oil and gas recovery are also ranked quite low in potential. That does not mean they are not worth doing; just that there are other technologies that are likely to bring greater benefits.

Do these technologies, taken in total, achieve the sort of levels of increased productivity that we need to keep economies of the advanced world growing? Or, to put the point that is worrying a lot of people now more directly: will our children have a lower standard of living than we do?

There is no easy answer. What I think you can say is technology develops in bursts, when it moves very quickly, but after that burst, incremental advance continues for many years. It also takes a long time, after the initial invention, to figure out ways of applying it. You can also say that if we are to go on increasing living standards, productivity increases have to come mainly in the service industries, for they represent 70 per cent of final demand. Working in the rest of the economy won't help enough.

Surely you have to take a pretty gloomy view of humankind to think that the ingenuity that has developed mobile telephony is somehow less active, less vigorous, less effective than the ingenuity that developed the motor car.

So we should be able to carry on improving living standards, even if it is hard to see quite how.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks