Hamish McRae: The Bank of England lurches from over-optimism to undue pessimism

Not good, not good at all; but refreshing in its candour and not truly dreadful. The Bank of England's new Inflation Report is much more pessimistic on both inflation and growth than its previous effort in May, itself more gloomy than in the one before that in February. Interestingly, the market reaction was that there was more scope for a cut in interest rates towards the end of this year, more probably early next, than they had previously expected, hence the sharp fall in sterling.

Let's take inflation first, then growth, then the implications for policy, including fiscal policy.

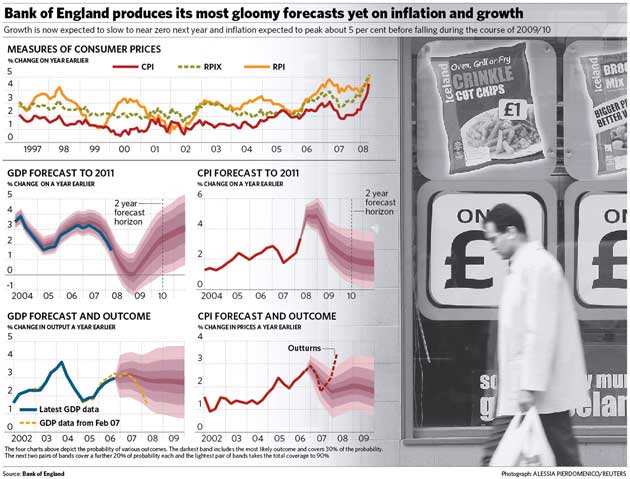

The first thing to say is that the targeted rate, the consumer price index, has started to show the same alarming rise as the retail price index and the old targeted rate, the RPI minus mortgage interest payments. You can see that in the first graph.

You could say that the RPI and the RPIX have given a better feeling for what has been going on and that must be right. It is certainly a shame that the target was switched, against the Bank's wishes, from the RPIX to the CPI. Had that not happened, the Bank would probably have moved a little earlier to head off this inflation crisis. That would have helped a bit, though only a bit.

There is, however, another way of reading that graph, which is to say that we should not be too alarmed by the surge in the CPI because the problem was already evident and the thing to look for will be a fall in the other two measures. If they start heading down, then there will be an intellectual argument for some rate cuts, even if the CPI numbers remain discouraging.

As for the prospects for the CPI and GDP, these are shown in the next two classic "fan" charts that the Bank has pioneered. The good thing about these is that they show probabilities rather than a single number, a much more realistic way of presenting forecasts. The spike in the CPI is significantly higher than in the previous report but does now look more gloomy than many private forecasts, particularly since energy prices are starting to subside. If global food prices come down through the winter this will be hugely helpful, for food is three-to-four times more important in the consumer index than fuel. I think it is quite possible that the inflation outturn will be towards the favourable end of the Bank's range. There is a long tail of higher prices still to come through as a result of the food and energy surge, but virtually no sign that these higher prices are forcing wages up. As long as wages stay under control the scope for rate cuts next year remains intact.

One of the reasons why inflation may turn out towards the favourable end of the range is that the Bank's forecasts for GDP are the glummest I have seen yet. As I have repeated ad nauseam, I am more worried about growth next year than this, and various private sector forecasts of growth in 2009 with a zero as the first digit – say 0.4 per cent or 0.6 per cent – certainly seem plausible.

The Bank does not publish its central forecast but deducing it from the graph, it looks to be closer to 0.2 per cent. That would be consistent with Mervyn King's comment that growth would be "broadly flat". No one, including the Bank, yet has a minus pencilled in for next year as a whole, but once you get down to these levels a technical recession (defined as two successive quarters of negative growth) is on the cards.

Can that be right? Well, it may be, but it may also be that the Bank is over-compensating for its earlier optimism. The Bank's economics team commands great respect, and rightly so, but it has undoubtedly miscalled this cycle. It has been completely frank about this, publishing two tables showing how it got things wrong in its February 2007 report. These are reproduced here. One shows how on inflation what has happened is way outside the extreme end of the projected range; the other shows how growth is at the bottom end – and it looks as though that will be outside the range too.

You can react to this in two ways. One is to ask why anyone should believe the Bank now. The other, more interesting, is to wonder whether having been far too optimistic in the past on both growth and inflation the economics team is being too pessimistic now. We all get things wrong and I have just been checking back to see what I was writing last year to help calibrate what I think now. I did warn about the housing boom and felt the Bank of England should have lent harder against it. But while I did worry about financial instability I thought the problem would be in derivatives and hedge funds rather than in the mainstream banks; and while I thought there would indeed be a global downturn around 2009, I did not see this inflation shock coming.

But now it seems to me to be that the Bank may just be starting to err on the gloomy side, particularly on inflation and maybe also on growth. Put it this way: the Bank is now ahead of the market in its assessment of the likely severity of UK economic problems over then next couple of years. I find that curiously comforting. These people are paid to worry on our behalf. As long as they are fully aware of the scale of the downturn then we can be assured they are on the case. It is when officialdom is in Panglossian mode we should be concerned.

So we can assume if inflation and growth do follow the path outlined, monetary policy will be eased. The lags between a change in interest rates and its impact on the economy take up to two years. So if you want to try and boost demand in 2010 you need to start soon. But the quid pro quo is that if you are confident that inflation will fall during 2010 you can start interest rate disarmament soon too. As soon as there is a window the Bank will act.

But what about the Treasury? This Bank's growth forecast makes a nonsense of its Budget forecast for growth in 2009 of 2.25-2.75 per cent. We all said it was absurd at the time and I feel rather sorry for the poor Treasury minions who had to sign off that forecast because they must have known that too. But they did because on any other growth assumption the Government's borrowing figures would have bust the fiscal rules. Obviously the reputation of the Treasury as a forecaster has been compromised and the next government will have to look at ways of giving the Treasury economics team a greater degree of independence. Meanwhile, the fiscal mess will have to be tackled in the Pre-Budget Report this autumn. I had been wondering whether it could be rolled on to the budget itself but now it can't be.

The bottom line here is that if the Bank is right about growth, the Government's borrowing requirement in 2009/10 will not be the £50bn or so it will be this fiscal year but something more like £75bn. The tragedy is that Gordon Brown has made exactly the mistake he sought all those years ago to avoid: allowing public borrowing to get out of control.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies