Hamish McRae: The shift to cheap money will not make borrowing it any easier

Economic Life

We are moving to a world where access to credit will be determined by administrative decision rather than by price. You can see that already starting to happen in Britain but it is likely to happen much more widely. It marks an important and inevitable retreat from the flawed notion that markets could correctly price risk.

It is important because it will mean that everyone – individuals, businesses, charities and so on – will be forced into different types of behaviour. They will have, most obviously, to build up good credit records and offer solid security if they want loans. And the shift is inevitable because the markets have failed to price risk properly and they won't be allowed to do it again, or at least not at all freely, for a quite a while.

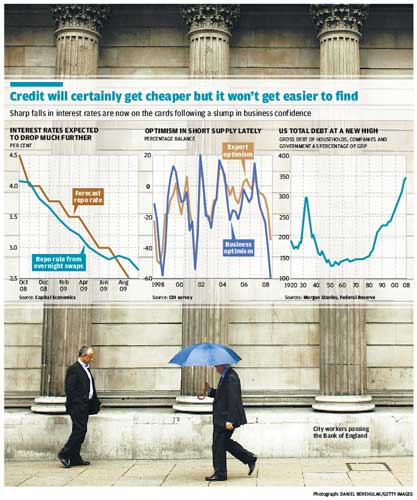

We are just at the beginning of the move to cheap money. The Bank of England's minutes explaining the case for cutting interests rates made it clear that there would be more cuts to follow. The market's reaction is that we will see base rates plunge over the next year and that sterling will fall sharply too, particularly against the dollar. Thus Capital Economics is predicting a fall in base rates to 2.5 per cent (see graphic), while ITEM now expects 3 per cent. As for sterling, it hit a five-year low against the dollar yesterday and the $1.50 level is being dusted down as a possible target.

The reason for this re-think of the interest and currency outlook is not just the Bank of England's changed view but reports from the Confederation of British Industry that show a serious deterioration in business outlook. Some results from the CBI's new survey are shown in the other graph. As you can see, until the middle of the year sentiment was holding up reasonably well. Suddenly in a matter of weeks that has changed, as though a switch has been flicked. That has happened right across Continental Europe too, though it is small comfort to know we are not on our own.

It is natural and inevitable to focus on these conventional indicators of the interest rate outlook and commercial sentiment. To some extent, cheaper money will give some support to the economy. It will not, however, give as much as it would have done in previous cycles because of this reassessment of risk that is being forced upon the financial services industry. At an individual level, it is fairly easy to see that, because it is already happening. The obvious area is mortgage finance, with lenders requiring a much larger deposit for new loans. The greater the government pressure on lenders to avoid repossessions, the more cautious they will become. That will affect not just loan-to-value ratios they will lend at, but they will also pay more attention to the security of the income of the borrower. So people in secure jobs, such as the Civil Service, will find it easier to get a mortgage than those in less secure professions, which I suppose includes journalism. That will change attitudes, not just in the careers that people choose but also, more generally, in the way they manage their finances. People will be forced to be more conservative, saving more, relying less on credit cards, putting more money aside for a pension. You could almost say Britons will become more German or Japanese in their attitudes to saving and spending, and less American – though, of course, Americans will change their habits too.

Naturally, this will not be a complete turnabout for everyone. We will still be allowed to misbehave if we want to and, in any case, any change will be gradual. But the effect of the new financial climate will be to tilt our behaviour back towards something more like the way people behaved before the easy money revolution. Expect the young to be a generation that is more conservative in financial matters than their parents.

It is harder to see how this will affect business life. In the first instance, it will favour larger, established companies rather than smaller, entrepreneurial ones. Something of that is happening already – witness the concern in the Government and among small business representatives that this sector will be squeezed. It will also favour large companies with strong balance sheets, rather than those with weak ones. That is all pretty obvious and, despite the Government's efforts, the result will be some retreat from the entrepreneurial spirit it has sought to foster. It is common sense that if it is harder to get risk capital, fewer businesses will be able to take risks.

But there will be gainers too. Small businesses that have access to capital, perhaps from family and friends, will be able to acquire assets on the cheap. There will be a lot more consolidation among large businesses as the stronger ones snap up the weak. That is happening at astounding speed in banking and will happen in other industries too. So there will be opportunities as well as pain. Both are already evident but the consolidation process in many industries has hardly begun.

It is harder still to try and think through the impact on investment in different asset classes, aside from the obvious. Financial intermediaries that have relied on leverage to produce returns, such as many hedge funds, are in trouble. Property funds will be under a cloud until the price of the underlying assets bottoms out. No one will want to buy complicated financial products for a generation. Simple products, such as equities, will survive, despite the hurricane that has blown through the markets in the past few weeks –if only for the simple reason that a world where there is less debt will be a world that needs more equity. That ought, in theory, to increase equity returns but quite how long that will take to come through (aside from the purely mechanical increase in dividend and earnings yield resulting from the share price collapse) is anyone's guess.

There is a further point. We are moving to a world where investors in established economies will be more risk averse, but that does not mean investors in the emerging economies will follow suit. As a result, they may have more opportunities for achieving high returns than they have had in the past few years. As they take those opportunities, the shift of power from West to East (and Middle East) will continue.

Finally, there are implications for global growth. The last boom was prolonged by the excessive creation of credit, particularly in the US. The final chart shows how, if you add together all types of debt – household, commercial and public – debt levels in America exceed those even of 1929. The world's largest economy will have to spend several years pulling that back, which does mean slower growth than would otherwise be the case. Paying off debt can be done gradually and, encouragingly, the creditworthiness of the US government does not seem to have been too damaged. But more cautious credit decisions will also mean slower growth than would otherwise be the case for the rest of us.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies