Hamish McRae: We need an exit strategy from the Bank of England's costly policies

Economic Life

So what's your guess: how long will it be before the Bank of England brings in its first rise in interest rates? One year? Two years? Longer still? I ask the question because we seem set with very low nominal rates for a long time yet, despite the growing evidence that our own economy – and more important the world economy – is starting to swing back towards growth. But near-zero interest rates carry costs, as does the Bank's quantitative easing programme, and both will have to be reversed some day.

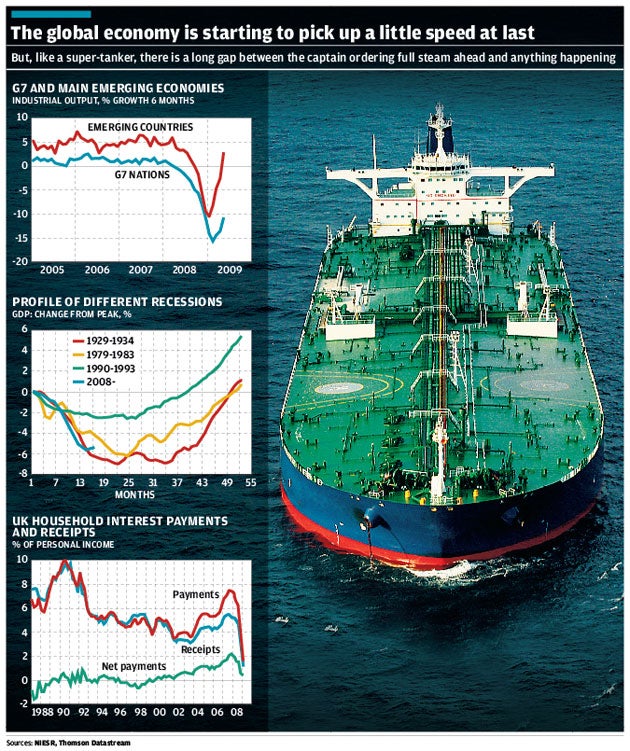

There is little doubt that the super-tanker that is the world economy is starting to pick up headway. The engines have been running flat out for some months but it has only been in the past couple of weeks that there has been real evidence of any forward movement. China and India have kept growing to be sure, with China becoming the world's largest car market in the first half of this year. But growth there has been more than offset by the collapse of output in pretty much the entire developed world. As you can see from the first graph, showing what has been happening to industrial output in the G7 countries and in the emerging world, we still have some way to go before output starts to run above the level of the previous six months, but the emerging world is back to growth.

Even here it is possible, just, that we have seen the bottom of this cycle. The monthly GDP estimates published by the National Institute of Economic and Social Research suggest that growth was up in June and that accordingly May will turn out to be the bottom. The three-monthly average for GDP is shown in the next graph, set alongside the recessions of the early 1930s, early 1980s and the early 1990s. As you can see, what has happened here is clearly very much worse that the 1990s, but if things pick up even quite slowly from now on, this downturn may well turn out to be less serious than the early 1980s. Mind you, we tend to forget quite how bad the early 1980s were: almost as bad as the 1930s, in fact.

Another small positive sign is that the International Monetary Fund has upgraded its global growth forecast in its latest World Economic Outlook. I wrote a few weeks ago during the catatonic gloom of the spring, when all the official forecasters were ripping up their previous efforts and competing with each other to lard on the glum more thickly, that at some stage they would have to start revising their forecasts up. Well, now that is starting to happen. Look for the Bank of England to do the same in its next inflation outlook report in a month's time.

If it does – and I think this is quite possible – then it will have to start rethinking what it does about interest rates and more immediately, quantitative easing. There was some huffing and puffing in the markets yesterday that the Bank had not extended its present easing programme. I expect that it will have to be continued, but there is a decent case for waiting another month to judge whether this is a real turning point. Views as to the effectiveness of the programme are mixed, with some argument that its main effect has been to enable the Government to borrow more cheaply, and that it has been little help to the commercial sector. Others, meanwhile, argue that we need more. My own feeling is that we just don't know. We have no past experience to go on, with the possible exception of the devaluation and money creation post-1931. Then the UK experience was relatively positive. We managed to escape the Depression in better kilter than any other large economy and without significant inflation, though as you can see from that middle graph, it was not until 1933 that things picked up. But the parallels are too distant for that to be much of a guide.

What I think is indisputable, however, is that we need an exit strategy. At some stage, and I expect during the life of the next parliament, there will have to be reconstruction of the National Debt. There will have to be fiscal consolidation, of course; we all know that. But separate from reducing the flow into the debt and starting to pay something back, we will have to deal with the stock of the debt, which seems likely to be more than 100 per cent of GDP. That will be the highest since the 1960s.

Debt reconstruction will have to be done against a background of rising interest rates. What is happening now cannot continue.

The bottom chart looks at the way in which very low interest rates have meant that households on average have seen their income cut by the plunge in rates. Of course the rates have fallen both for borrowers and for savers, but netted out, it is savers who have lost most. This cannot continue because people will adapt. If banks don't offer reasonable returns on spare cash, other institutions will create financial instruments that will offer a better deal. These might include a mix of corporate bonds, for as the company sector returns to reasonable health its debt will become more secure. We might even find mortgages being securitised again, particularly once the housing market recovers. The whole point about the present level of interest rates is that it is artificial and therefore cannot be sustained for long. The market assumption that rates are stuck where they are now for the foreseeable future seems to me to be a questionable one.

That leads to a further point, the balance between financial intermediation by banks and by securities markets. A century ago securities markets were relatively more important vis-à-vis the banks. International trade was largely financed by bills of exchange, cross-border investment by international bonds. Banks by contrast rarely made longer-term loans, restricting themselves to short-term finance. Long-term loans, in Britain at least, were really only for property purchase, and were largely the province of the building societies.

We are going to see more and more restrictions on the banks. That is inevitable. And that will have the equally inevitable consequence that people and companies will have to go elsewhere for capital. That "elsewhere" will be the financial markets. It is hard to see quite how far this trend will continue, but to put it in perspective, it will be a partial reversal of the shift towards bank intermediation that took place in the 1960s, with the development of the inter-bank market and the syndicated term loan. The key point here is that the longer that interest rates are held artificially low, the greater the pressure for people to bypass the banks.

At the moment the authorities are still thinking in terms of how to encourage (or bully) the banks into financing the upturn; or to put it the other way round, how to stop a lack of finance aborting the upturn. My point is that what they will actually do is to make banks less important and markets more important. Not sure they have figured that one out yet. The super-tanker may be moving again but it will take a long time to pick up speed.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies