Hamish McRae: When Irish eyes are smiling again it will be good news for the UK too

Economic Life: The EC was critical of Ireland's performance but there are small signs that confidence is returning

To what extent does cutting a budget deficit really restrict demand? Yesterday there were better-than-expected borrowing figures for February, suggesting that the Treasury may undershoot its debt forecast. That, of course, is welcome ahead of the Budget next week. It is, however, a measure of the scale of the disaster of Britain's finances that the fiscal deficit this year may turn out to be only about £165bn, about 12 per cent of GDP.

I am afraid it does not change the big picture of a deficit that is the highest in the G7. Nor does it change the task ahead – of eliminating the bulk of the structural deficit over the next four years. We have, after all, to recognise that there will be another economic downturn at some stage in the future and get the country's finances back on to a decent footing before we are struck by that. Realistically, we have to make some sort of start down that path in the coming financial year.

That raises the inevitable question: does fiscal consolidation necessarily curb growth? The problem is that there are two countervailing forces at work. On the one hand, there is the mathematical impact of deficit spending by government. If it borrows, say, an extra £100m and spends it widening a motorway, that money goes into the hands of the company doing the job, its workers, suppliers and so on. They then spend more themselves, further increasing demand. Economists call this the multiplier and, in theory, an extra £100m spent should boost demand by, say, £250bn.

But there is another force pushing in the opposite direction – the impact of such spending on business and consumer confidence. If a policy is known to be unsustainable, people adapt in advance to the consequences. Companies cut back on investment and consumers on their spending (the latter may briefly advance spending if they expect VAT to go up, but that is temporary).

There is some evidence to support this. A survey of executives in this newspaper yesterday showed that the business community would like deficit reduction to start in the coming financial year.

Andrew Sentence, a member of the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee, made an important point when he said: "Progress in putting public finances on a sounder footing can increase confidence and reduce uncertainty about future economic prospects, providing a much better climate for a recovery in private- sector demand."

The trouble is that, while confidence must have some effect, it is hard to quantify how large it is in any particular set of circumstances. What we need is something very hard to do in economics: have a controlled experiment. Well, it is not quite that, but there is some most interesting evidence from across the Irish Sea.

More than 90 per cent of the population of the British Isles lives under one jurisdiction – the UK – but nearly 8 per cent (and some 22 per cent of the land area) is administered by another – the Irish government. The financial structure, pattern of home ownership and other economic variables are quite similar, actually becoming more similar as manufacturing has declined as a proportion of the economy in the UK and financial services have grown in Ireland. There are differences, of course, most notably Ireland's adoption of the euro. Nevertheless, what happens in the Republic does give some sort of guide to what might happen here.

Well, we all know about Dublin's extraordinarily tough budget last December, which cut civil servants' salaries and made other economies. Ireland, unlike Greece and unlike the UK up to now, has taken the tough decisions. Public consumption is being cut by 3 per cent in a country where the unemployment rate is running at 14 per cent. When the budget came out, the Economic and Social Research Institute in Dublin, the country's foremost economic study and forecasting group, allowed for it giving some boost to confidence. But it still expected the Irish economy to shrink by 0.25 per cent this year, with growth in the second half more than offset by continuing contraction in the first half.

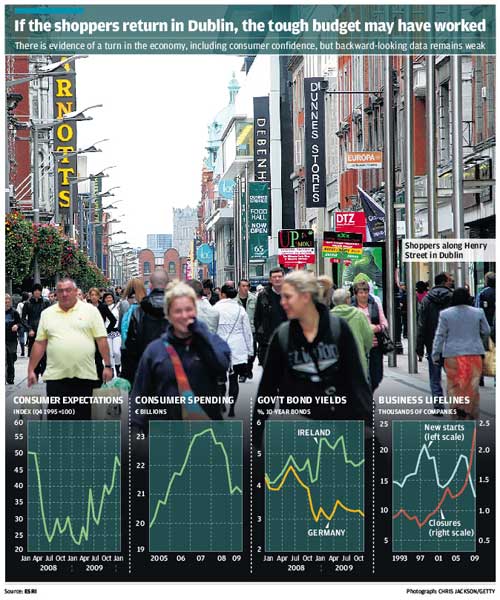

The next ESRI report is not due out for another month and the figures will take longer still to emerge. Meanwhile, the European Commission has been pretty critical of the country's performance. But there are small signs that confidence is returning and a real possibility that Ireland might surprise on the upside this year. The evidence as yet is very thin but it is worth noting. First, there was a sharp rise in consumer sentiment in January, with expectations climbing sharply following the budget. True, they fell back a little in February, as the first graph shows, but the numbers are much higher than through the whole of last year.

Next, there are some signs of life in the housing market. Lettings in Dublin have strengthened, with rental levels up 15 per cent since the autumn, according to agents Sherry FitzGerald. There are reports of bids coming in higher than asking prices, something unheard of for more than a year. The ESRI still thinks prices will decline this year and this stronger market may be just a Dublin thing, but clearly something is happening. Certainly, sales of existing homes are running at three times the (very low) level of a year ago. Third, as one of our thoughtful readers has noticed, there has been a big rebound in goods passing through the port of Dublin: the volume of Ireland's exports is up more than 7 per cent on a year ago. He also spotted that electricity demand was higher in January, which may have been a weather thing, but that it has stayed up year-on-year even as temperatures have increased. Finally, there are other statistics which support the view that "something is happening", including car sales (though helped by the government's vehicle scrappage scheme) and industrial production, up from its very depressed level of a year ago. I would not want to make too much of all this and the long haul remains ... well ... a long haul.

As you can see from the other graphs, Irish consumer spending is back to the level of 2005; the country has to pay nearly 2 percentage points more for its government borrowing than Germany, and business closures are still at very high levels, but this is what you would expect. Most data is a picture of the past and the more comprehensive the statistics, the longer they take to come out. But it is the little bits of data, anecdotal stuff such as the reports of the estate agents, and twitchy little nuggets such as electricity demand, which give a hint of what is happening right now. So we will have wait to see how swiftly the suggestions that confidence is returning will result in a bounce in real demand.

But if the boost to confidence from the Irish budget more than outweighs the additional fiscal drag it has placed on the economy, then that is good news for the UK and indeed for other governments that face severe fiscal retrenchment. If it works in Ireland it might work here too.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies