The retail giants of yesteryear have fallen - but cheering feels wrong

Global Outlook

It’s difficult to look at the proposed $6.3bn (£4.1bn) purchase of Office Depot by Staples and not get the feeling that the deal is a rearguard action against a world that no longer wants or needs either of them.

These office supplies companies are like two old drunks propping themselves up outside the pub, getting their breath back while the party continues indoors.

There was once a time when these two businesses commanded such a hold on their market that American authorities prevented them from merging. That was in 1997. Now the chances of their proposed merger being stopped are virtually zero, and rather than being an attempt to corner the market, it seems more like a desperate last throw of the dice.

On the face of it, these are still two big businesses – something approaching $27bn in combined annual revenue and almost 60,000 employees in stores across the US. That’s a lot of people selling a lot of office supplies. The trouble is, the bottom line for both has ceased to grow and a big top line is no guarantee that a business can survive.

If you want to know why these two companies are under the cosh then tune in to any American radio station. There’s a Wal-Mart advertisement playing on a loop at the moment in which the world’s largest retailer touts its lines. “Some office supply stores have closed their doors,” the voiceover goes, as if they’ve shut just to annoy people. The truth is that many office supply stores have closed their doors because of Wal-Mart, and before that because of Office Depot and Staples themselves.

It is not just because of competition from Wal-Mart and other big retailers like Costco and Target, which also sell office supplies. Office Depot and Staples also face stiff competition from Amazon, and as a result margins have moved in ever-decreasing circles over the last decade.

The market is full of smaller players too, offering everything from funky business card design and printing to shabby-chic furniture. After all, no self-respecting modern entrepreneur wants an office that actually looks anything like an office.

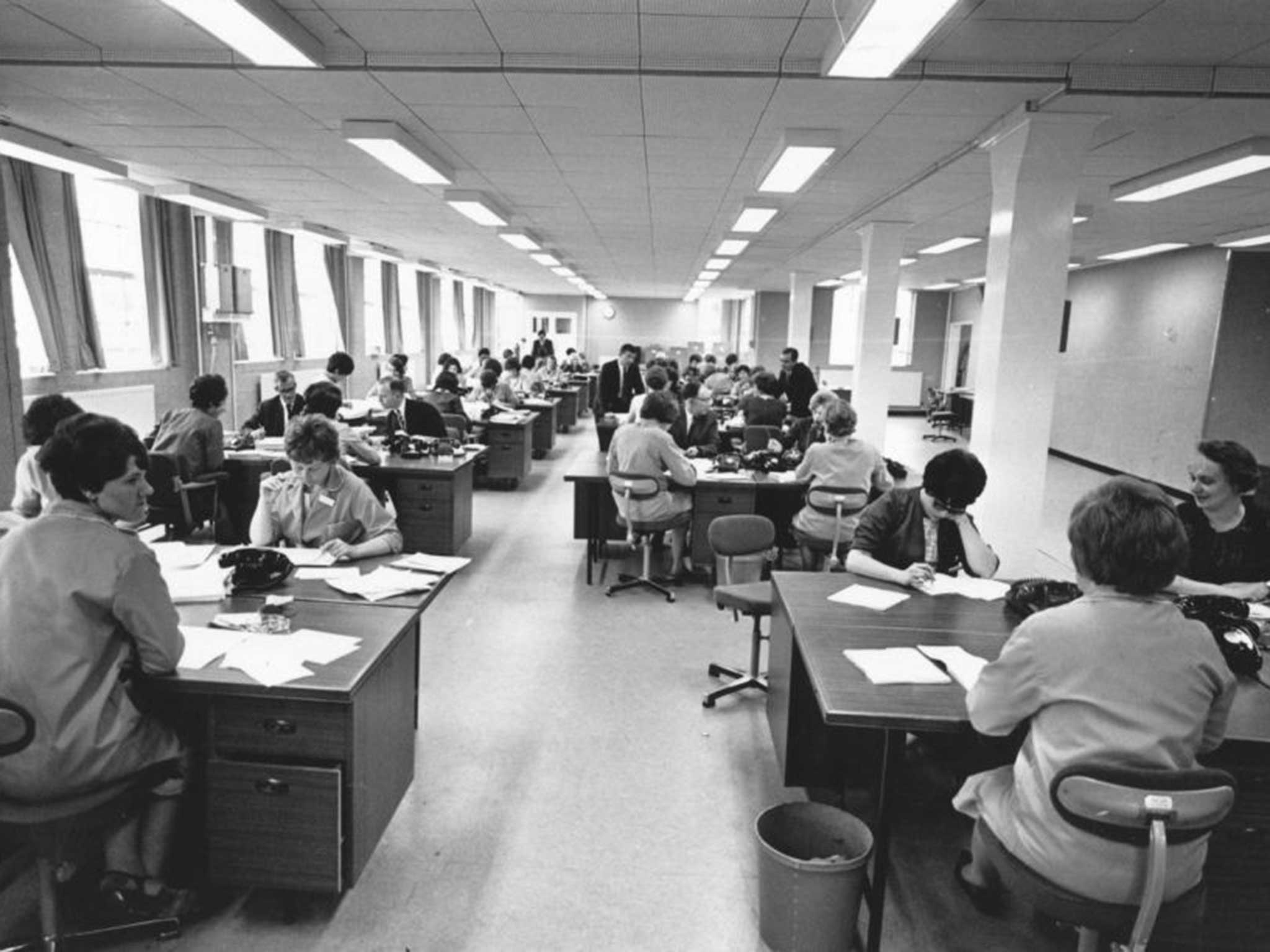

Office Depot and Staples’ business models are also being challenged in another way. Technology might simply change demand for what they are selling to the point of obscurity. Go into a Staples or Office Depot and you’ll find everything that someone starting a business would need ... 15 years ago – rows of landline phones, answerphones, envelopes and Rolodexes. Smart phones and downloadable software have maimed this kind of business just as much as Amazon or Wal-Mart.

Merging the two businesses is probably the only sensible route to take – they’re not quite moribund in the same way that Blockbuster or Circuit City were in their last months, and Staples might just have management who are aggressive enough to take the steps needed to save the businesses. Sadly, that means closing underperforming stores and streamlining. It also means a lot of people losing their jobs.

I hope that together Staples and Office Depot can survive. I have my doubts and part of me feels like they are fighting a losing battle against the inexorable march of time. That’s how much the world has changed: Staples and Office Depot put most small office suppliers out of business; now the same thing is happening to them.

Cheering for Staples and Office Depot feels wrong. But before we know it, all we will be left with is Wal-Mart and Amazon. And much as I dislike shopping, that’s not a pleasant thought.

Share buybacks: what are they really good for?

As part of the deal to buy Office Depot, Staples announced that it would suspend some of its financial activities, including its share buyback programme. We hear about buybacks all the time, and they have become as accepted a part of the financial landscape as petulant bankers or Donald Trump’s hair. But are they really all they’re cracked up to be?

The idea is that unless they are going to invest it, companies can and should return some of their cash to shareholders. This is generally done by paying a dividend or buying its own stock. The stock is purchased in the open market through a broker, then cancelled – thereby leaving fewer shares, and increasing earnings per share and theoretically the share price too.

I’ve never been particularly convinced, especially if Warren Buffett’s two key buyback principles are applied: first, that the capital is genuinely excess or can be borrowed without a significantly impact on balance sheet risk; and second, that the stock is fundamentally undervalued.

The former is the easy bit, so Apple borrowing $6.5bn last week to pay dividends and fund buybacks was perfectly sensible, despite the $170bn in cash it has tucked away around the globe. It’s the latter bit that’s difficult and where my faith in stock buybacks comes unstuck.

I have never once met an executive who didn’t think their company’s shares were undervalued. Never, not even during the first dot-com boom, have I come across an executive who didn’t declare that their stock was “good value” – or some such patter.

And when the bubble burst and the market was tanking, the mantra simply became “the market doesn’t understand our business”.

The trouble is, many business executives don’t really understand the market either. Once a share buyback plan has been announced, companies are pretty much committed to it – regardless of where the market happens to be at the time the buyback is put into action. So we can end up with companies spending millions, in some cases billions, buying their own stock while the market is making an exaggerated move in either direction.

Lehman Brothers was still buying its own stock when everyone else knew it was doomed. If a Wall Street titan can get it so wrong, why are buybacks treated with such complete certainty?

More and more buybacks are used as a short-term prop for the share price rather than as a part of a larger capital management programme. Meanwhile the S&P 500 index yields a paltry 1.9 per cent.

If companies have cash to return, dividends are significantly more appealing to investors. So investors need to demand more of them.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies