The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

2016: The year that the volcano of inequality exploded

Brexit, the election of Donald Trump and the capitulation of Matteo Renzi in Italy: many have concluded that 2016 was the year the “left behinds” of the Western world struck back. But is this interpretation correct?

This was the year that the “left behinds” of the Western world struck back.

Or, at least, that’s the lesson that politicians, economists and commentators have taken from the series of volcanoes that have erupted over the political planet in the past twelve months.

Brexit, the election of Donald Trump and the Italian referendum were all, of course, different contests with very different propositions at stake.

One was a once-in-a-generation decision on whether to continue with Britain's 43 year membership of the European Union.

The second was a four-yearly election to decide who will occupy the White House.

The third was a plebiscite on constitutional reform in Italy called by a young and hubristic prime minister, Matteo Renzi, who saw so little chance of losing that he promised to resign if the people voted no.

But uniting them all was that each involved a populist surge against the political establishment and a campaign animated by disaffection with a form of globalisation rigged, we were told, in the interests of a privileged minority of economic “elites”.

Barack Obama has said that Donald Trump’s unexpected victory in November over Hillary Clinton was propelled by a “suspicion of globalization, a desire to rein in its excesses, a suspicion of elites...a fear [among people] that their children won’t do as well as they have.”

Similarly, our own Prime Minister Theresa May has argued that Britons are upset at “the emergence of a new global elite who sometimes seem to play by a different set of rules”.

And Ms May has talked more about the importance of reducing inequalities in her five months as prime minister than previous Conservative politicians did in their entire terms of office.

In Italy analysts noted that the poorer regions of Italy voted overwhelmingly against Renzi’s proposed reforms in this month’s referendum.

And there was a similarly pronounced split in the UK between well-off and less well-off regions in the Brexit vote.

In the US the traditionally Democrat-voting Rust Belt states, home to many communities that have been hollowed out by de-industrialisation, swung unexpectedly and dramatically to Trump and the Republicans.

Trump himself claims he was carried to victory by “the forgotten men and women” of America.

But is this story correct?

Was this a global democratic backlash against widening income inequality and rampant economic unfairness?

In several important respects the answer is no; it is too simplistic.

There are awkward facts that don't fit the narrative.

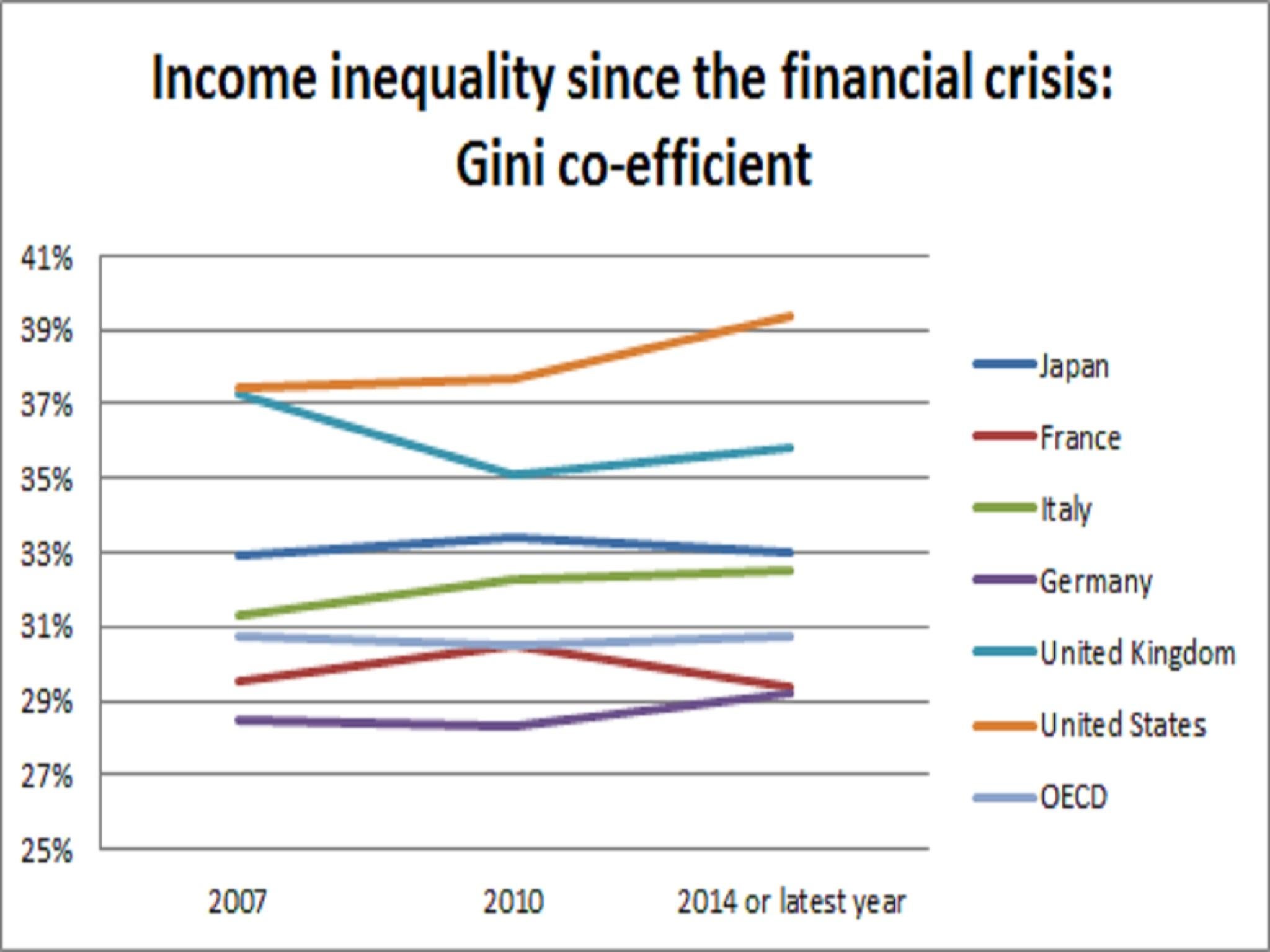

The standard statistical gauges of income inequality and wealth inequality in much of the Western world have not, actually, shown any dramatic increases since the global financial crisis of 2008.

The Gini-coefficient – a statistic that sums up the level of inequality across the entire income distribution - has been flat in the UK since 2007.

In other major economies there have been no dramatic upward moves.

Not so unequal?

Far right parties are also on the march in countries such as Sweden and Finland where income inequality is quite low.

The exit polling from the US general election showed that – contrary to many perceptions – a majority of poor Americans voted for Hillary Clinton rather than Donald Trump.

The average Trump supporter was surprisingly well-off.

Relatively asset-rich homeowners in the UK predominantly voted to leave the EU.

Age was as important as income in this year’s political eruptions.

Large shares of the over 60s voted for Brexit, regardless of their living standards.

Yet a majority of 18-24 year olds voted to Remain.

In their referendum, by contrast, 80 per cent of Italian young people voted no.

The campaigns were not black and white in terms of pitting populists versus elites.

The Italian constitutional reforms were opposed by some influential figures in the liberal political establishment – including the former prime minister Mario Monti – on the grounds that they risked opening the door to untrammelled rule by the populist Five Star Movement.

So we should be wary of mono-causal explanations of complex and multifaceted phenomena such as election results.

And we should certainly be reluctant to explain a host of votes across different countries through a single, simple, narrative.

There are a host of other crucial factors in each of these votes, from simmering racial resentment to anxiety over immigration flows.

Cultural nostalgia played a part, as did, it seems, Russian computer hacking and rampant online misinformation.

Nevertheless, the sense among politicians and analysts that something is wrong economically in Western countries – and that inequality was an influence in this year’s political revolutions – is not baseless.

Polls show elevated levels of economic disatisfaction across a broad sweep of countries.

And there are legitimate grounds for that.

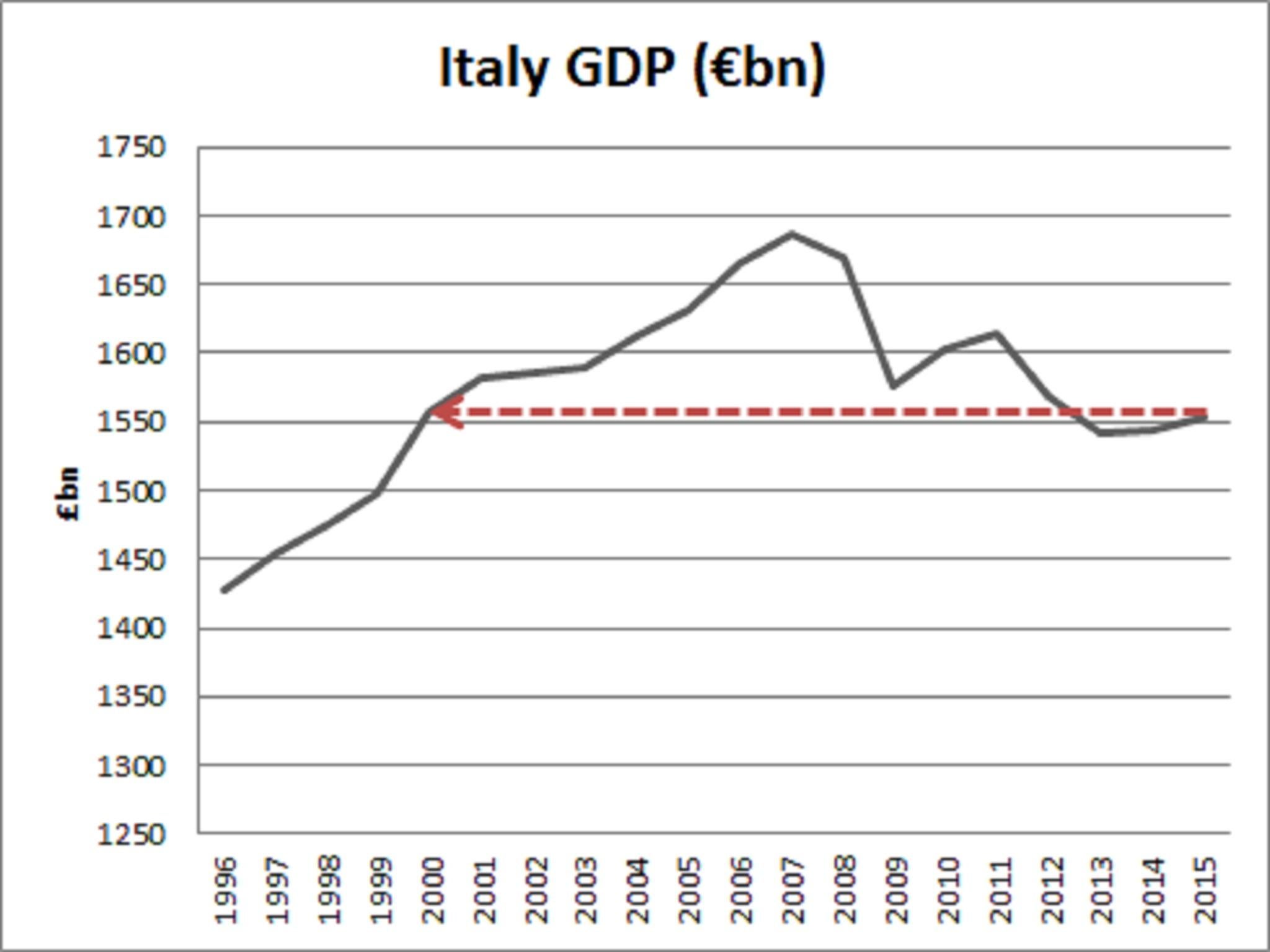

Italy, in particular, is a story of grand economic failure. The level of GDP in the economy is the same as it was in 2000. Youth unemployment is 36 per cent.

Italy's lost 15 years

This reflects the wider calamity of economic policymaking in the eurozone since the financial crisis, where bone-headed austerity has also hammered Greece, Spain, Portugal and even France, resulting in levels of unemployment that ought to be utterly unacceptable.

But policy has failed elsewhere too.

In America the median average inflation-adjusted full-time male wage – despite a very recent increase – is no higher than it was in 1980.

In the UK real average wages are still lower than they were when the financial crisis broke almost ten years ago - and according to the Bank of England this is the weakest decade of wage growth since the 1860s.

Average living standards in Western countries might not have collapsed since the financial crisis but wages and incomes are certainly far below where most families expected them to be a decade ago - and people experience that as a real loss.

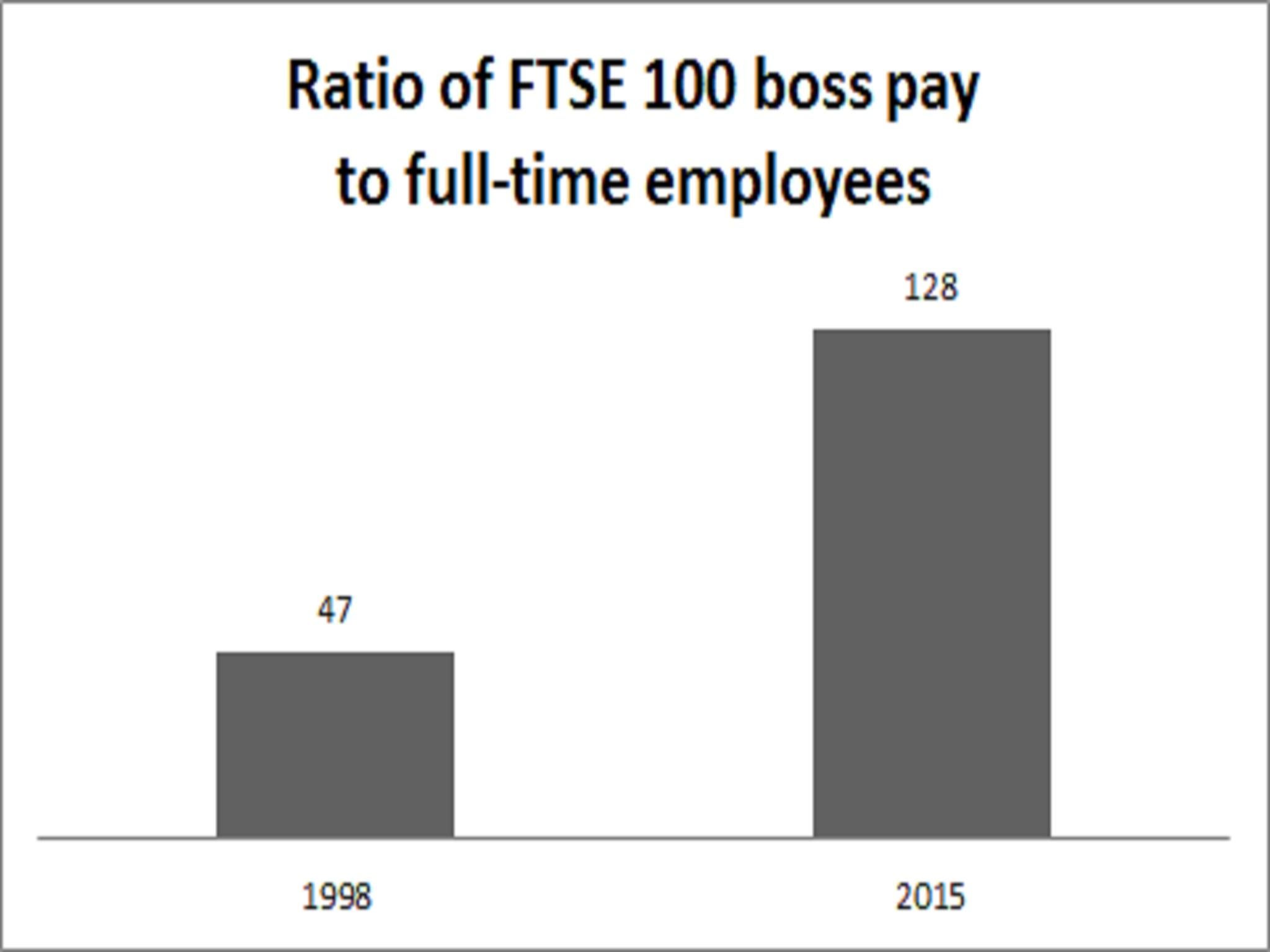

Meanwhile, rewards for a small minority at the top of society are still rising strongly.

The ratio of the pay of the average FTSE 100 company boss is 128 times that of the average worker, up from just 47 times in 1998.

Bosses' pay

In America the situation is even more extreme.

In 2014 the chief executive of Time Warner was paid $34m, 629 times as much as the median worker at the company.

At Microsoft, Satya Nadella, received remuneration worth $84m, 615 times the average pay of his employees.

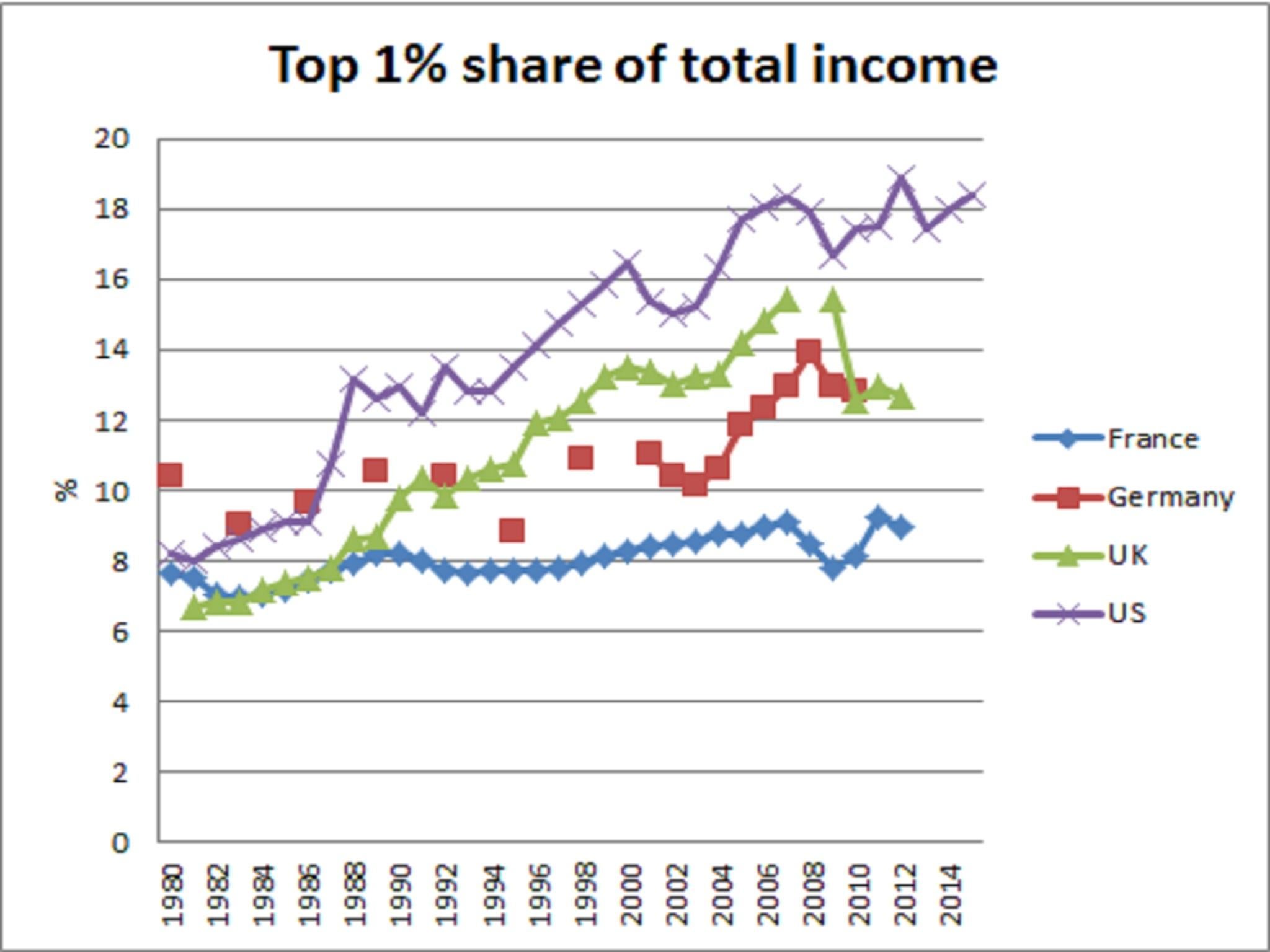

This is part of a long-term trend.

The share of total incomes going to the top 1 per cent of the population has been rising since the 1980s, particularly in the UK and the US.

In America the share is back to levels last seen in the Gilded Age of the 1920s.

Rewards at the top

The idea that these kinds of spectacular rewards for a tiny minority of individuals merely reflect their immense personal productivity is unconvincing as an empirical proposition – and it certainly doesn’t convince the general public.

Underlying the disaffection is the poisonous legacy of the global financial crisis in 2008 and the almost total absence of accountability for the individuals whose greed and incompetence plunged the Western world into its most painful economic shock since the 1930s.

As the former Bank of England financial regulator Robert Jenkins put it last year:

“Investigations have been legion. Large fines are frequent. But no bank has lost its banking license. No senior executive has gone to jail. No management team has been prosecuted. No board or supervising executive has been financially ruined. Many have kept their jobs, their salaries, their pensions and their perks….Is there any wonder that the public has lost faith in finance?”

In Europe this political and regulatory failure to restructure the bloated and ailing Continent's banks - facing up to bad loans and imposing losses on shareholders and debtholders - is a significant contributor to the eurozone's wider economic malaise.

Surveying this bleak landscape, is it really any wonder that so many people are angry?

That they are prepared to vote in ways that may be economically self-harming but which convey that anger at what they perceive to be a rotten system?

No; the political eruptions of 2016 were not solely a consequence of economic grievances.

Yet it would surely be naïve to imagine those grievances did not help to prepare the ground for these shocks.

More can be expected in 2017.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments