National Insurance U-turn: How much will it cost? And where will the money come from now?

What is the size of the hole this opens up? And where does this cost rank in terms of other fiscal U-turns by the Government in recent years?

The Chancellor, Philip Hammond, on Wednesday announced that he would scrap the planned increase in Class 4 National Insurance contributions for self-employed workers that he had announced in last week’s Budget.

This would have affected an estimated 2.5 million workers, although, in conjunction with the simultaneous scrapping of Class 2 NICS, no one earning less than £16,250 a year in 2019-20 would have been worse off.

How much will this U-turn cost? Where might the new money come from instead?

And how does this cost rank in terms of other fiscal U-turns in recent years?

How much will this cost?

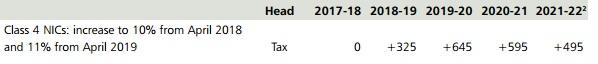

According to the Budget’s documents this take hike was due to bring in £325m in 2018-19, £645m in 2019-20, £595m by 2020-21 and £495m, in 2021-22.

So a total of around £2bn over four years.

Is this a lot?

Jeremy Corbyn called it a “black hole” in the House of Commons at Prime Minister's Questions. But this is an exaggeration.

The hole in 2021-22 amounts to less than 0.06 per cent of the total projected tax take in that year of £869.5bn.

The bigger problem is that this minor reform was hoped to be the first step towards equalising the tax treatment of the income of the employed, the self-employed, and people who are owner-managers of their own businesses.

The Office for Budget Responsibility last year forecast that the increasing trend towards "incorporations" alone could open up a £3.5bn hole in tax receipts by 2021-22.

And in last week's Budget upward revisions to the OBR's self-employment level forecast pushed down projected tax receipts by £1bn a year by 2020-21.

The overall cost of the lower NICS rate paid by the self-employed relative to the employed is estimated at around £5bn a year.

How does this compare to other Budget U-turns in size?

In May 2012 George Osborne U-turned on his plans to introduce VAT on hot takeaway pasties after a backlash.

The Treasury estimated at the time that the pasty U-turn itself cost £40m a year. A separate climb down on levying VAT on static holiday caravans at the same time cost £30m a year.

Much more substantial was Mr Obsorne’s 2015 U-turn on a planned cut to tax credits, which would have cost around 3.3 million households an average of £1,300 a year.

This reversal meant the Government would raise £9bn less over the five years to 2020-21 than it originally hoped, according to the official Autumn Statement costings.

The cost in 2016-17 alone from this reversal was £3.38bn.

How might Mr Hammond fill the fiscal hole?

The figure is so (relatively) small that it will not be particularly hard for the Chancellor to offset it by fiddling with other taxes.

For some context, in the Summer 2015 Budget Mr Osborne unveiled a host of stealth tax rises on areas such as insurance and dividends that raised £5.7bn a year by 2020-21.

And in last week's Budget Mr Hammond raised £930m a year by 2021-22 by lowering the tax-free allowance on dividend income from £5,000 to £2,000.

Alternatively, helpful upward revisions in tax income forecasts from the OBR might lead the Chancellor to decide he doesn’t need to bother offsetting the U-turn at all.

That’s what Mr Osborne did over tax credits in 2015, when he pointed to £27bn of extra fiscal room over five years.

So it's really no major fiscal drama?

The danger inherent in the U-turn is not the particular fiscal damage from the reversal but rather the politics of it and what it implies for future tax policy.

If such a minor (and socially progressive - all of the cost of the total NICS reform would have been borne by the top half of the income distribution according to the Resolution Foundation) increase in the national tax base cannot be delivered, the chances of providing the public services that people demand, while also balancing the budget, look bleak.

Also ominous for the direction of the public finances is that the Conservatives are committed in their 2015 manifesto to raising the threshold for higher rate income to £50,000 by the end of this Parliament and also hiking the tax free personal allowance to £12,500.

The OBR has not scored these because they are not yet official Government policy, but it does warn that, together, they would imply a cost of up to £3bn a year by 2019-2020 in foregone tax revenues.

A lesson from this U-turn is that Theresa May seems to want to take manifesto tax pledges seriously - even when they make no fiscal sense.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments