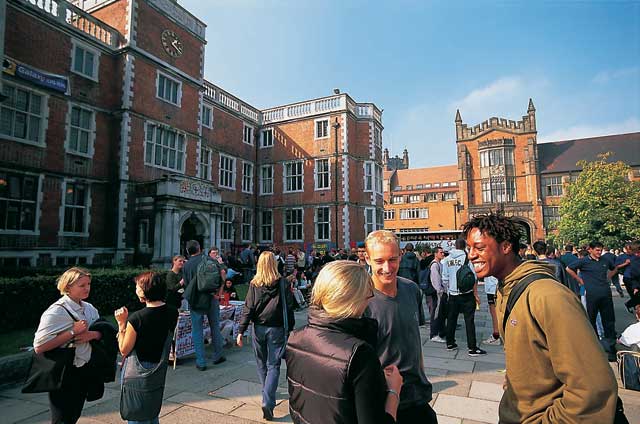

From underachievers to high-flyers: Was Newcastle right to admit students on lower grades?

It is 10 years since Newcastle launched a plan to take local applicants on lower A-level grades. Lucy Hodges looks at its effectiveness

In the sixth form during his final two years at secondary school, Peter Hirst enjoyed himself. Although he was studying three A-levels and was keen to get a degree, he didn't know how to ensure he achieved the good grades to gain admission to a leading university. Neither of his parents had gone on to higher education and his Gateshead school did not have large numbers of boys going on to take A-levels.

"I was underachieving," he says now with the wisdom of hindsight. "I was not very interested in school even though I was always in the top group."

But then Hirst met someone from Newcastle University where a pioneering scheme had been set up to encourage young people to go into higher education – and he never looked back. The Partners Programme offered a university place on slightly lower A-level grades than would otherwise be required and a summer school where young people could demonstrate their potential by completing study projects.

Hirst, now 26, realised it would be the best way for him to attend a good university. He applied and was accepted, passing the summer school programme and getting his A-levels at grades CDE, which were lower than the BBC demanded by Newcastle for his course in applied communications. For Hirst, his three years at Newcastle transformed his life. "I met people from a big range of backgrounds and from all over the country," he says. "I have always been competitive in sport, but I had never been competitive in my academic work. Now I was having to work quite hard to compete. That was good for me, and the social aspect was fantastic as well. I grew up during that time."

He came out with an upper second degree, having spent a good deal of his spare time helping the university with its widening participation measures, and he is now a director of two companies, one of them being Kidology, which provides market research for companies that make products for children.

Manisha Singh, 23, underwent a similar experience. She was able to get into Newcastle to study law with A-level grades of AAC when most applicants are required to have three As. She has now qualified as a barrister and is applying for a pupillage.

The Partners Programme was in the vanguard of widening participation programmes in the UK, enabling teenagers from families and schools that were unfamiliar with higher education to set their sights higher. When it was established 10 years ago, there was a lot of nervousness about whether it was a good idea to lower the entry grades for some students and whether the scheme would work. Newspapers were full of articles about how independent school pupils would be penalised if their potential university places went to state school pupils who had scored lower grades than them. Newcastle got round that criticism by asking for, and being granted, 800 more student places.

"It was quite a leap of faith at the beginning, because we were taking people who looked as though they had lower attainment," says Lesley Braiden, the director of marketing and communications at the university. "But we were reassured because the summer school assessment gave us the extra confirmation that we needed."

The first 41 students from schools on Tyneside arrived at Newcastle University via the Partners Programme in 2000. Since then, more than 1,500 from all over the North-east, Cumbria and parts of West Yorkshire have followed. The number of schools and colleges participating in the programme has grown from 45 to 111, and 4,000 young people from these schools and colleges are applying to Newcastle University each year, including 800 applying through the Partners Programme.

The programme has borne fruit, according to Braiden. If you look at the figures of young people applying to university from the North-east, there has been a rise of 10 per cent between 1999 and 2007, she says. But Newcastle University has experienced a 52 per cent rise in applications from the North-east region in that time. In addition, over the same eight years, the numbers actually entering higher education from the North-east increased by 12.5 per cent, whereas the numbers entering Newcastle University rose by a remarkable 86.9 per cent.

Professor Ella Ritchie, the pro-vice-chancellor for teaching and learning, says that the programme has had a definite "halo effect" on partner schools, meaning that more and more young people have applied to university as the scheme has taken off and proved popular in their local schools.

Both Ritchie and Braiden are hopeful that the coalition Government will continue to fund this important widening participation work. Without it, Sir Martin Harris said in his recent report from Offa, the Office for Fair Access, the percentage of students from disadvantaged backgrounds going to university would be lower than it is.

And without it, Hirst and Singh would not have had the chances that have transformed their lives.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies