The brain drain leaving Britain 'vulnerable'

Our top graduates are shunning jobs as researchers – and we're falling behind in the race to recruit from abroad, according to a report from Warwick's vice-chancellor. He explains why to Lucy Hodges

Are the best and brightest students going into research? If not, what's to be done – and should we worry that Britain could cease to be a global player in future? The answers, according to a report sent to the Universities Secretary, John Denham, and published exclusively in The Independent today, is that some of the best graduates may be quitting academe, and that we are right to be concerned.

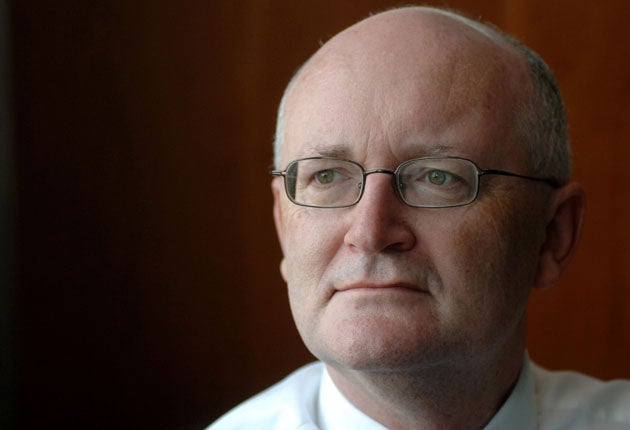

The statistics do not give cause for optimism, according to Professor Nigel Thrift, vice-chancellor of Warwick University and author of the report, which is one of eight investigations the minister has commissioned into key areas. At the moment, the number of researchers for every 1,000 people employed in the UK lags behind the EU and OECD averages, as well as several other European competitors, the US, Japan, Australia, New Zealand and Korea.

"Perhaps more concerning is data which indicates that the proportion of researchers per thousand employed in the UK has increased only slightly over the past 25-year period, whilst in some major competitor countries, the proportion has increased significantly," says the report.

"The world does not stand still. International competition will continue to intensify and the UK may find itself in a vulnerable position if it does not take further action."

Figures show that in all academic disciplines the percentage of researchers under 35 has decreased. In the future, things will not be helped by the fact that the British student population is expected to shrink in line with the birth rate.

To stimulate demand, we need to introduce schoolchildren to the idea of a career in academic research, says Thrift. And at university, undergraduates need to be given more idea of what a research career entails. The number of PhD researchers has continued to rise only slightly and the rate of growth has slowed noticeably, according to the report.

Growth in overall PhD numbers can be mainly attributed to overseas students. Indeed, some subjects rely on overseas students for postgraduate numbers. Recently the British Academy reported that the number of UK students applying for science PhDs had fallen from 65 to 57 per cent in the last 10 years, compared with a 79 per cent growth in doctorates overall, says the report.

This reliance on overseas students, though welcome, makes us vulnerable. Almost half of all postgraduate research students in the UK come from abroad. Some are concentrated in vital subjects, such as engineering, physics and chemistry, and Britain is heavily dependent on postgraduate recruitment from just seven countries, particularly China.

That is worrying because of the big effort that some countries are now making to recruit overseas students. Both the US, our main competitor, and mainland Europe have undertaken drives to increase postgraduate numbers from abroad. The US, EU member states, Australia and New Zealand all have attractive packages to win a bigger share of this lucrative market. By contrast, Britain gives funding to fewer than 10 per cent of international postgrads.

Worse, the UK is actually cutting bursaries for overseas postgrads, with the axing of the Overseas Research Student Awards Scheme and the reduction in the number of Chevening scholarships. This is short-sighted, in Thrift's opinion. Instead, he says, we probably need a new national scholarships scheme, to pull together the arrangements that exist at present.

"This is more important than people think," he says. "There is a real and genuine competition for the very best people around the world. On the whole we have done well in the past, but whether we will in future is another matter."

He recommends a national scheme to enable academic researchers to spend time in industry, and for researchers in industry to come into academe. "The more different people are exposed to one another, the more chance you have of getting good ideas."

He also wants to see better nurturing of researchers early on in their careers. Young researchers can have a lonely and insecure existence, moving from one contract research job to another, not knowing if they will be employed from one year to the next and uncertain of their career prospects.

"Researchers are more mobile than ever before and a 'brain drain' of both promising and elite researchers from the UK continues to be a clear and present danger," says the report.

The funding problem: researchers have their say

*James Legget has a PhD from Nottingham University and works as a postdoctoral researcher at the Henry Wellcome Labs for integrated neuroscience and endocrinology at Bristol University.

"I originally wanted to be a vet but found my research project so fascinating in my final year doing animal science at Nottingham that I decided to stay on for a PhD. It was hard work and not very well paid, but I got the doctorate in three years and moved to a postdoc contract that lasted three years. I am now in my second postdoc position at Bristol. I love my career and

Bristol is great but it is hard work.

Funding is the most difficult problem for young researchers. You can't apply for your own funding, so you have to find senior researchers to work with. The idea is to apply for research funding with someone more senior than you, because problems arise when you cannot guarantee to a research council that you will be employed by the university for the whole period of the research contract. There is a lot of uncertainty and that can be stressful, but I'm still doing it, so it can't be that bad.

I would like to apply for a fellowship but you need a good publication record, and mine isn't good enough yet. I think Britain definitely loses a lot of good researchers because the career path is so tough and there are only so many places at the top of the pyramid."

*Charlie Hindmarch, 30, works as a research assistant for the department of neuroscience at Bristol University.

"My first degree was from Plymouth University in marine biology. I did a Masters in biochemical pharmacology at SouthamptonUniversity and decided I wanted to do research. First I worked in industry - for Pfizer - and then I got a job as a research technician at Liverpool University before moving to Bristol.

The hardest thing to cope with is the funding. It becomes more competitive as you move up the pyramid, and you have a panic attack about your job after three years, because although your salary is small, it is essential.

I am married with a mortgage and a child, so the prospect of not being able to compete is frightening. In one way it is very unstable, but in another it is quite stable because you know when your money is coming to an end and you have the choice of asking your boss to seek funding for you or to look for a job.

As you move up the ranks you get to learn how to work the funding system. This university is good at nurturing your skills by laying on courses and mentors.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks