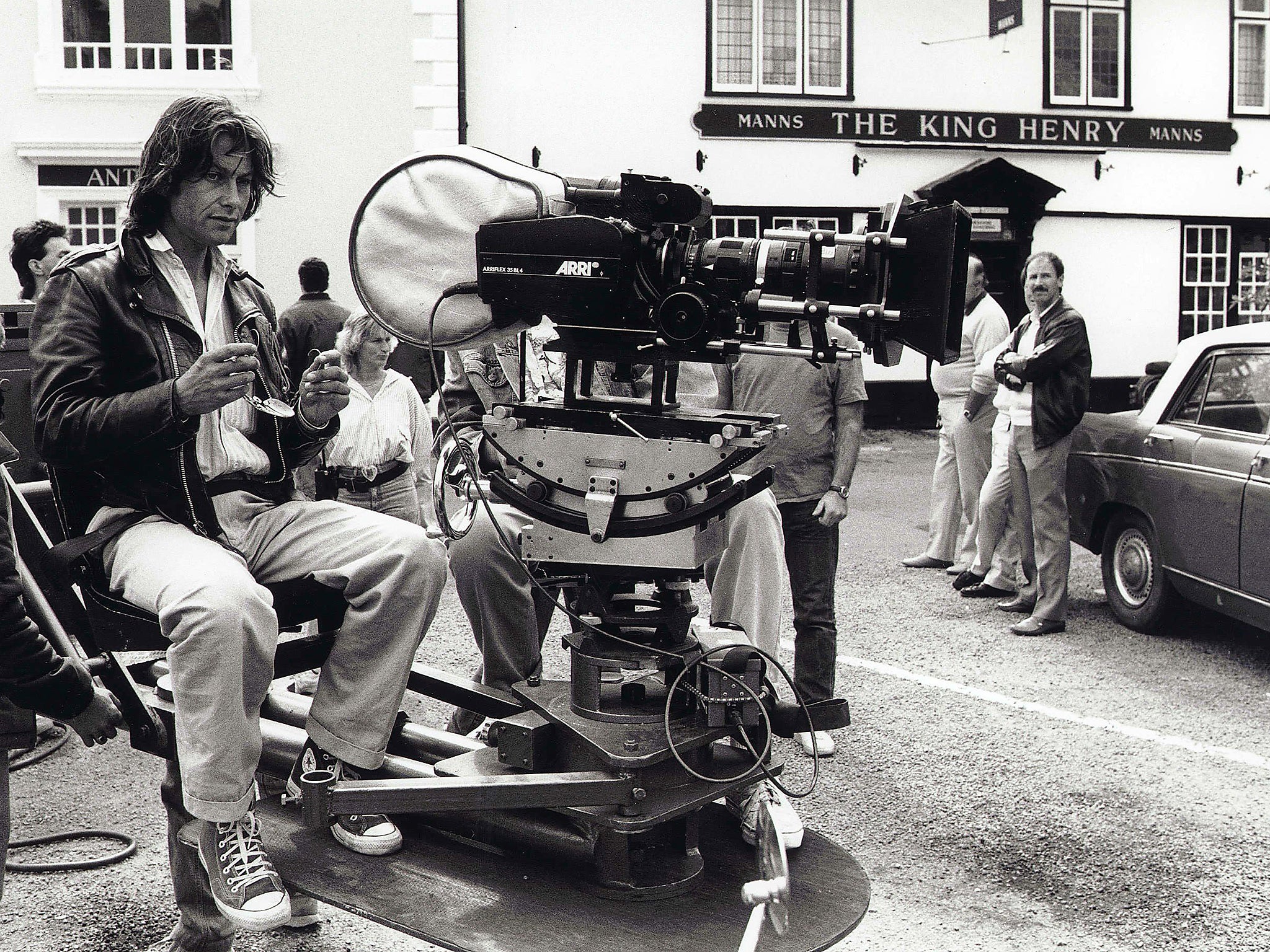

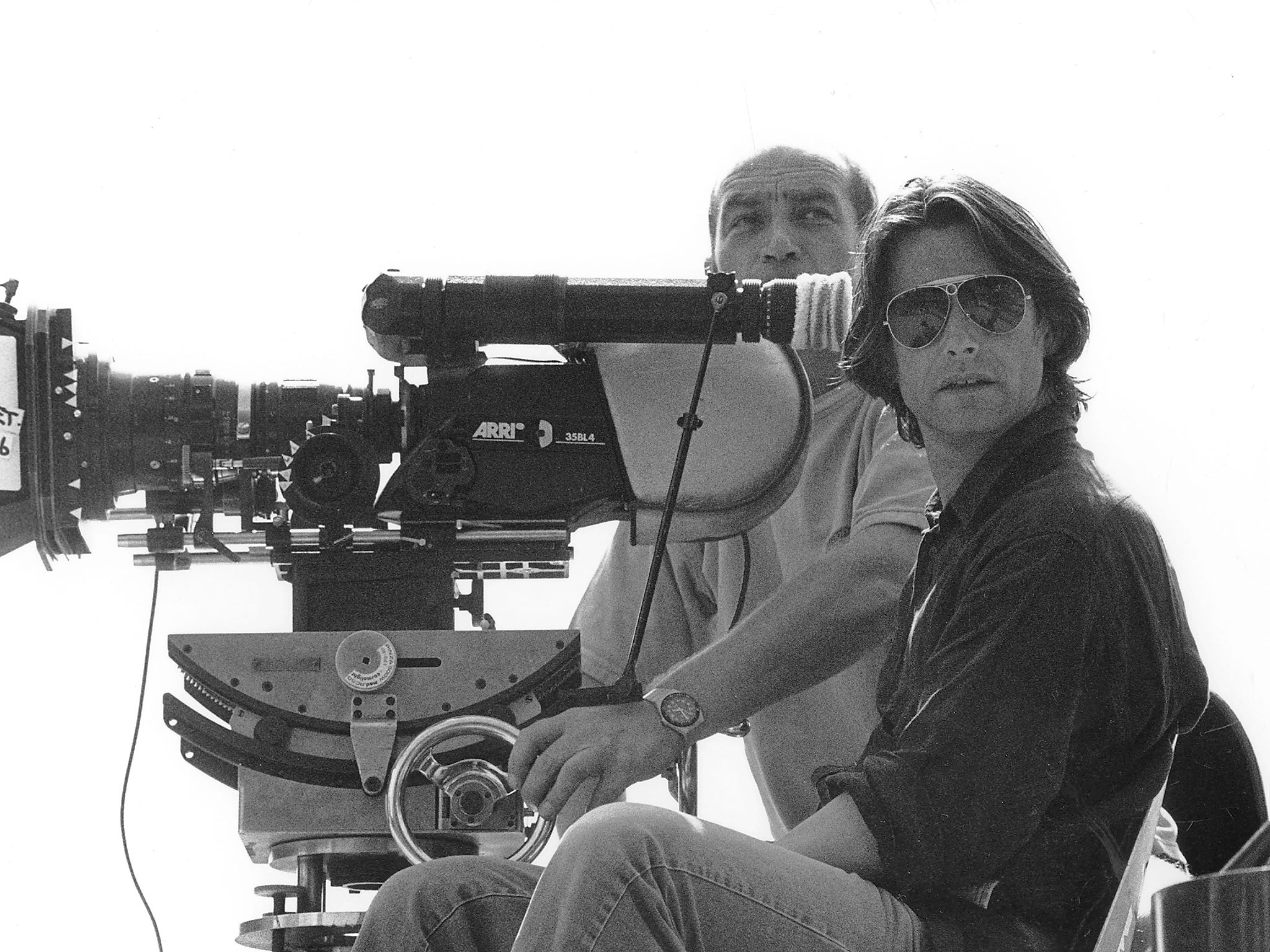

Bruce Robinson on the inspiration behind Withnail, disbelief in politicians and his hatred of smartphones

It's been 30 years since the alcohol-fuelled 'Withnail and I' was released but despite drinking up to five bottles of red a day – and the thread of booze running throughout his work – director and screenwriter Bruce Robinson says drinking doesn't define him. Matthew Barnett meets him to ask why alcohol is such a key motif for his characters

Driving towards the Herefordshire home of writer and director Bruce Robinson was already proving something of an ordeal. Here I was, about to interview the creator of what must be the UK’s and possibly the world’s most iconically cool film, Withnail and I, and I was driving a non-descript VW Polo and feeling distinctly sober. Of course, I should have been in a clapped out 1960s Jag, dragging on a Gauloise and recklessly swigging from a bottle of Haut Brion while listening to Hendrix.

Arriving at the weathered front door of Robinson’s picturesque 16th-century farmhouse, I half expected it to be flung open by Uncle Monty with a cry of ''my dear boy!'' and to be warmly – too warmly – embraced, but instead found myself in front of an elegantly svelte Robinson whose eyes twinkled at me from behind blue tinted specs.

Introduced first to a large and very elderly dog (''he should be dead by now'') and then his artist wife Sophie (''coffee or tea?''), we progressed to an enormous hall-like room where we sat on low sofas. I was immediately struck by a large portrait of Keith Richards with fag dangling from a pendulous lower lip. "Oh, that’s by Johnny Depp," Robinson informs me. "It's painted on cigarette papers. Actually, along with his other talents he’s a bloody good artist." I agree.

He regales me with an anecdote concerning the famously louche Stones guitarist, who was Depp’s friend. "We meet for a drink and he's leaning on the bar, smoking. He says, 'well you smoke, do you wanna fag?' I politely tell him that it’s not legal to which he replies 'who's gonna stop us?' And, of course, no one’s going to stop Keith, but they will stop me!'' We both laugh and I say "that sounds like Withnail" to which Robinson replies '"actually he is!"

It’s 30 years since Withnail and I was first screened and it remains Robinson’s (somewhat frustratingly to him) magnum opus. Describing it as '‘like a colostomy bag'’ that trails around with him, his attitude towards the film is almost that of an early and never-to-be-recaptured love affair: poignant memories of newly kindled passions and freshly felt sensations, the pang of lost youth. And lost friends. His muse and flat-mate Vivian MacKerrell, who provided so much of the inspiration for Withnail, died more than 20 years ago aged 50. It was he who famously inspired the moment when Withnail relieves his desperate need for a drink by swigging lighter fluid.

And that's one of the all-pervading leitmotifs in much of his work, drink. It permeates not only Withnail but also his other major film, Hunter S Thompson’s novel The Rum Diary, which Depp asked Robinson first to read, then turn into a screenplay and then direct. Both describe essentially bibulous worlds populated by figures that are out of control and running out of time.

I ask him whether this is true?

"Oh absolutely, the two elements that are central to all of my work are drink and shit. The Peculiar Memories of Thomas Penman [Robinson’s autobiographical novel] is about the latter. I had a curious childhood in that I never knew who my real father was and never saw a photograph of him until I was 68. Turned out he was an American lawyer my mother had known during the war. She never revealed his identity to me: a bizarre form of cruelty.

"What is strange is how I may have subconsciously perceived the truth. When I was around 12 or 13 I used to buy Dell comics and then began to imitate an American accent – my mother must have wet herself! It’s come through the genes! Sperm filled with an accent!"

Robinson ascribes his deep-seated hatred and distrust of the establishment to his mother’s betrayal and the fact that he had no father figure to admire or aspire to. "That’s why I never believe any of these politicians and so called leaders because I never believed the primary authorities in my life – my parents." His recent book, a monumental exegesis of Jack the Ripper – They All Love Jack – amounts to a sustained critique of establishment hypocrisy, nepotism and malfeasance, all of which he feels is as real now as it ever was.

So what about drink? Withnail and I is, at one level, a gloriously anarchic, alcohol fuelled romp that begins in a shabby genteel London flat and moves to a remote shabby genteel farmhouse, with all the antics and chaotic capers of a latter day Sterne. It is the film’s quality of sustained hysteria and illogicality that makes it so extraordinarily funny, compelling and also so tragic. An eschatological wind blows through it from beginning to end.

I mention an anecdote concerning Stephen Fry, who once told me that he never drank while writing and was amazed at how people such as Scott Fitzgerald could drink so much and write so well.

"The day red wine ever got in the way of my writing I would stop drinking, but it is the oil of what I do. I can go to my office and rage and rant, but booze doesn’t define me – it’s just a bottle of red wine. I’ve never lost a day’s work through drinking red wine."

Nonetheless, I had read that he was drinking up to four of five bottles of red a day and would have got through one by 10 in the morning. Was this true?

"Oh easily, yeah, but I have an enormous tolerance of it I suppose – though only red wine. I have no interest in Guinness and gin, whisky or vodka. And anyway, why is it considered such a fucking evil? What I consider to be evil are these pissing smart phones – I’d rather my 13 year-old child were drinking a Chambertin or an Haut Brion than constantly looking at a filthy fucking phone. Anyway, I don’t drink a lot, just enough to make the words work."

And indeed, it does seem to be a peculiarly effective creative fuel in Robinson’s case. It was after a long period of abstinence and while starting work on the script for The Rum Diary that he came off the wagon.

"What are you going to do if you’re sitting in a room for 10 or 12 hours a day, on your own? You can’t converse with anybody, have the radio on or listen to music, you’re there with this fucking piece of white in front of you and if you can’t hear the words you better have some red wine. That’s how I get into the creative process. You know how it is, you go to a party and they’re all standing there – stiff-arsed with their backs against the wall – and an hour later they’ve had a few gins and they’re trying to fuck each other and roaring with laughter. It’s crazy, but in a sense this is what red wine can do for a writer, it puts you in a place where you can start hearing the voices again. It’s a daft way of describing it but that’s how it is for me."

Was this also true when he was writing Withnail?

"Oh absolutely, 1000 per cent. Vivian and I would go around the bins in Camden and Kentish Town, collecting used Guinness bottles worth four pence each. When we had two suitcases full we’d go to the nearest off-licence where we’d swap them for an eleven-and-six bottle of Greek plonk, or some other filthy shit. Then back to the flat where we’d drink and discuss and fall asleep, then wake up and go round the bins again. It was madness."

Once again the memory of MacKerrell drifts into the room, like a ghost. I suggest that some people’s lives, though empty and even tragic, are lived poetically and provide inspiration. Was this true of his friend?

"He absolutely inspired me. I have never had such intense conversations in my life as I had with Viv. He was a public school boy from an upper middle-class background, while I was a secondary modern kid who didn’t even know what poetry was. He used to start the day with a cup of black coffee, honey and hashish: what he called the Baudelaire Principle ..."

With this in mind we briefly discuss another of Withnail’s immortal characters, Danny the Dealer, who drawlingly challenges the protagonist to try some of his wonderfully named pheno-dihydrochloride-benzorex before being told to "shove it up your arse for nothing and fuck off while you’re doing it". Robinson’s rendition is so brilliant that we both start laughing and I compliment him on its accuracy. "Well I bloody well taught him the accent. I was going out with Lesley-Anne Down who had a hairdresser who spoke exactly like that [he repeats the accent], and it just entered the creative mix."

For a moment Robinson is distracted by something and gets up to look through a window towards a distant hillside. Returning he laughingly tells me that he thought he could see what looked like "a sheep eating a pheasant".

"Do you know," he continues, "in those days – and it’s never been the same before or since – I used to go out every night with pals and have something to eat and drink and have a laugh, but I’d be aching to get back to this little Olivetti portable that I had – I wanted to write that story. I just couldn’t stop it."

There’s a pause and he looks reflective. "Anyway, I’m yakked out for the moment and need a piss."

It’s the perfect cue for a break…

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments