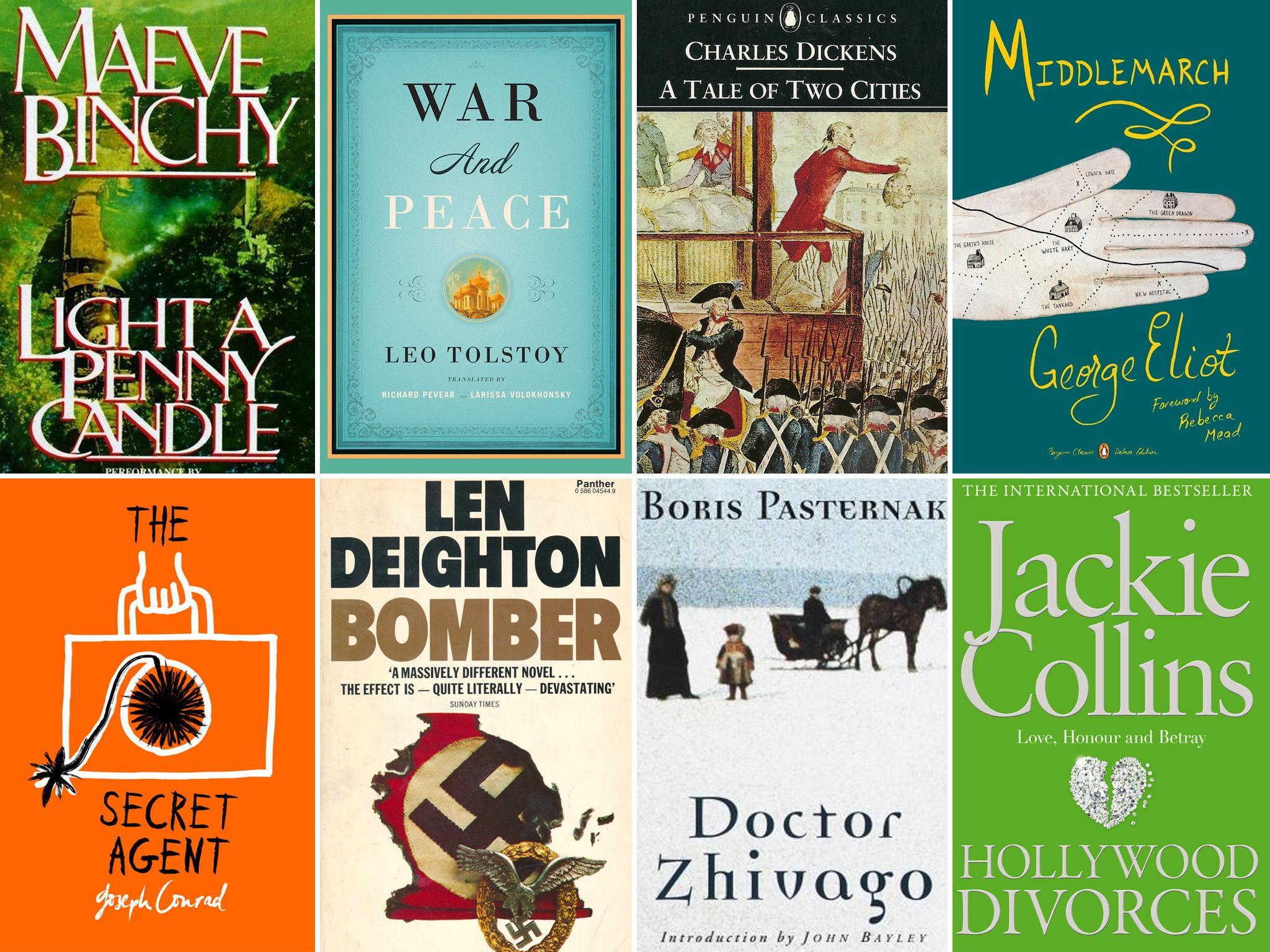

Paperback writers: Can ‘pop-lit’ give literary classics a run for their money?

In the traditional pantheon of ‘great literature’ there is no room for authors such as Maeve Binchy and Len Deighton, whose rollicking reads meet with mass-market appeal but critical snobbery. Self-confessed history man Robert Fisk questions why their work should suffer in comparison

In the very early 1980s, a most accomplished Irish writer and journalist would sit in her little home in the County Dublin village of Dalkey, hammering away on her first novel. It told the story, starting in the Second World War, of two families and of two young women, one Irish, the other English. Opposite the novelist, on the other side of Sorrento Road, in another little cottage, was a Trinity College Dublin PhD student who was writing his thesis on Irish neutrality in the Second World War. Each night, around 11pm, the novelist and the student would look through the curtains across Sorrento Road from each other to see if the other was still at their desk. If one was still at work, the other would go on writing for another hour.

The novelist was Maeve Binchy. The student was me. And when Maeve published Light a Penny Candle in 1982, she handed me a copy of her book in the middle of the narrow road between our two cottages. “In memory of the long days and nights of typing at windows opposite each other,” she wrote on the first page. Her book was 540 pages long. When I published my thesis under the title In Time of War a year later, it was just over a hundred pages longer. Maeve became a best-selling novelist. Tens of millions of copies of her books have been sold in 37 languages, and they are, as we journos like to say, “a great read”.

They are not “great literature” of course, because they are far too popular and grasp the hearts of too many people. Light a Penny Candle’s theme of love and betrayal – especially betrayal – touched the simple fears of Irish and British women in a chauvinist world moving out of the fear and austerity of war. By strange coincidence, Maeve’s book and my own work on the Second World War had something in common. Elisabeth, Maeve’s principal English heroine – neither of us used “hero” for women – is sent by her parents to neutral Ireland in the war, because it is safe from air raids. A theme of my own work was that in the Second World War, neutral Ireland was not very safe at all; according to an Irish minister, “Eire” was in “a condition of limited warfare” with both Britain and Germany, both of which had plans to invade the newly independent country.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.