Phillip Knightley: A cheap way to deliver quick results as newspapers slug it out in hard times

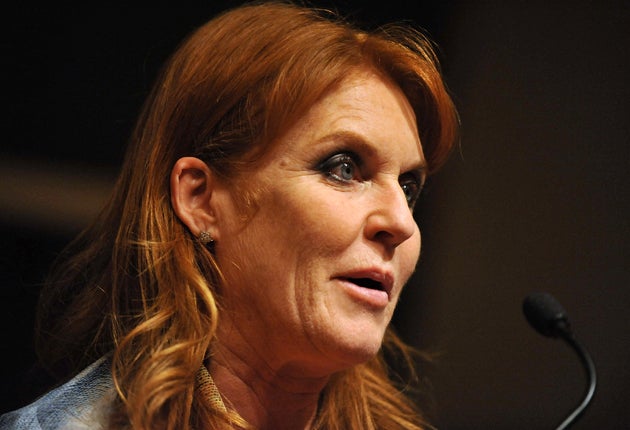

The Duchess of York offers to "sell" her former husband's services to a businessman for a promise of £500,000 and $40,000 in cash now.

The businessman turns out to be "the fake sheikh", the News of the World reporter Mazher Mahmood, and the Duchess finds herself splashed all over the front page of the newspaper.

Lord Triesman, the Football Association chairman, tells a young lady of his acquaintance about an alleged plot by the Spanish and Russians to bribe World Cup referees in South Africa. The young lady has a concealed tape recorder and Lord Triesman finds himself splashed over the front pages of the newspapers.

A good week for undercover reporting? Or a shameful example of invasion of privacy, entrapment and shoddy, lazy journalism?

The ethics about undercover reporting are far from clear. The journalist has to weigh the public interest of the story and the importance of what is being revealed, against the opprobrium of the technique and the victim's feeling, often shared by the reader, that they have been lied to and deceived. Donal MacIntyre, who went undercover many times for the BBC, said: "The golden rule is this: as an undercover reporter you must never encourage anyone to say or do anything they would not otherwise do if you had not been there."

This is a judgement call and without hearing the whole tape – rather than the extracts provided by the newspaper – a difficult one to make. Most of the reporters I worked with at The Sunday Times in the 1980s opposed the use of deception on principle. They took their lead from a statement by Benjamin C Bradlee, executive editor of the Washington Post: "In a day when we are spending thousands of man-hours uncovering deception, we simply cannot afford to deceive."

So why do newspapers do it? Going undercover is considered glamorous. Acting a role that exposes wrongdoing or greedy and bad behaviour attracts some journalists, particularly those seeking to become the heroes of their own stories.

But above all, at a time of falling circulations and editorial financial restrictions it is a comparatively cheap form of journalism with a quick result. Standard investigative journalism is expensive, often open-ended and uncertain. Many stories simply fail to stand up.

All that Mahmood and the News of the World needs is a tip-off that suggests the victim might be susceptible to an approach, and the external trappings to make Mahmood appear believable (a Rolls-Royce, a decent suit, an expensive flat or hotel room) and his own plausible manner.

His success rate is remarkably high. He claims to have helped convict 231 criminals using his undercover approach. But in July 2006 his methods came under scrutiny when three men were cleared at the Old Bailey of plotting to buy radioactive material for a terrorist "dirty bomb".

Similarly, an exclusive about an alleged plot to kidnap Victoria Beckham collapsed after police found that Mahmood's main informant had been paid £10,000 and could not be considered a reliable witness. Roy Greenslade, professor of journalism at City University, London, tried to publish a photograph of Mahmood but the News of the World obtained a temporary injunction claiming it was necessary to protect his privacy.

Wikipedia put the photograph on its website in 2008. Apparently it escaped the Duchess's notice.

Phillip Knightley was a member of The Sunday Times Insight investigative team in the 1970s and 1980s

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments