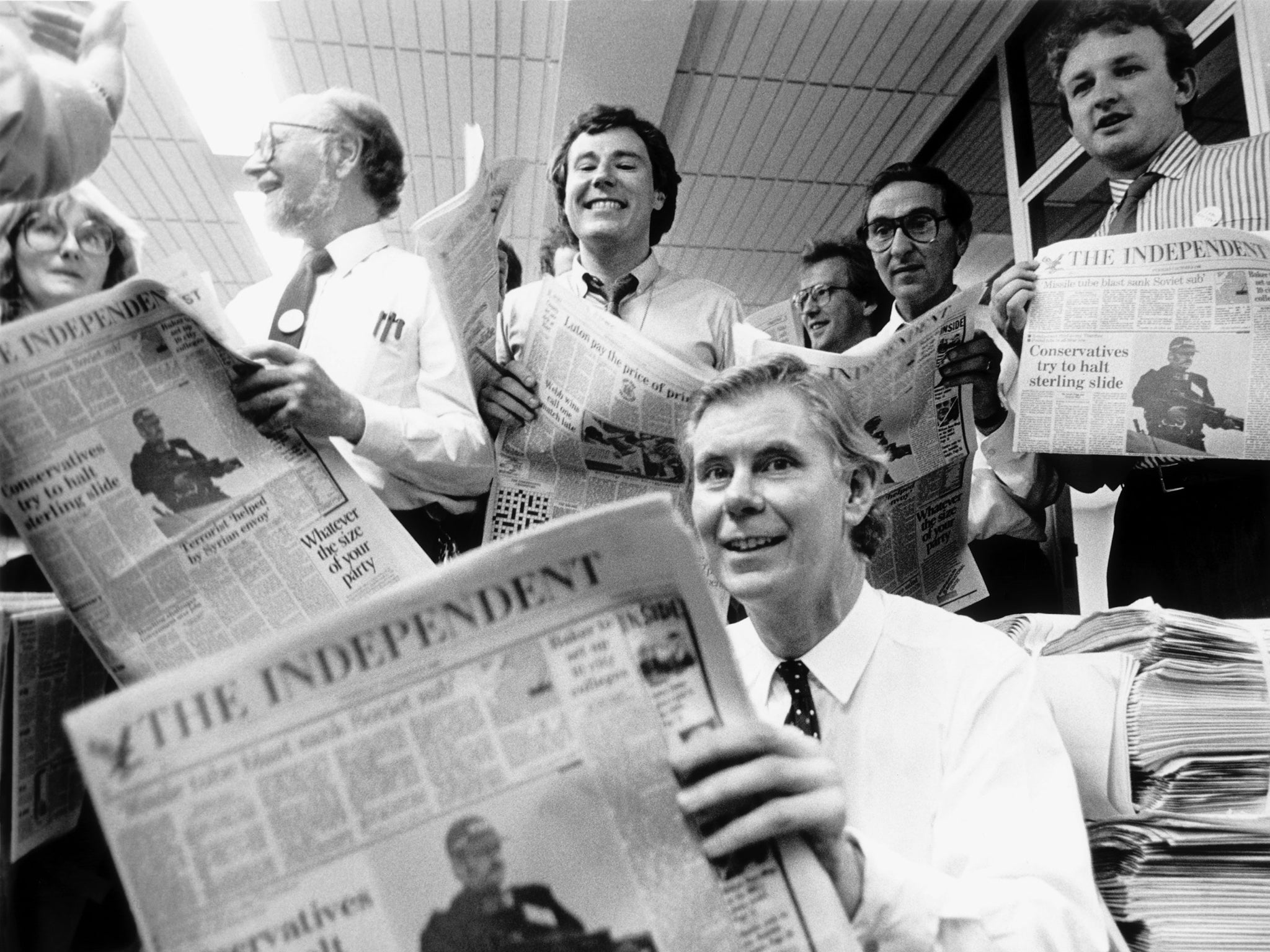

The Independent newspaper's founder on a dream that lasted because readers shared it

To say that somebody is independent minded indicates no particular profile – it simply defines an attitude

We had done everything we could think of to prepare for the launch of The Independent. We had corrected the Saatchi advertising campaign, whose original slogan was “I am. Are you?” Unfortunately, some colleagues who took to wearing button badges with these words received such strange looks when travelling on the Tube that we realised it would have to be changed. It became the famous “It is. Are you?”

We had endured the agony of trialling full versions of the newspaper with potential readers. To begin with they weren’t very impressed, but gradually our approval ratings became more encouraging and our self-confidence improved. We had also organised a full run, half a million copies delivered in bundles to every newsagent, to see whether our distribution system was up to the job. The first time we tried, it wasn’t. But it operated without a hitch when we went live.

Then as we were getting the first issue ready, I suddenly realised that we had failed to prepare a statement of purpose. There would be nothing in the newspaper to tell our new readers what we were about. I asked my colleague Matthew Symonds to turn out something swiftly to put on page three. Matthew, along with Stephen Glover and myself, had left the Daily Telegraph some months earlier to get the project going.

The best of The Independent's photography

Show all 48I have re-read the piece to see how far we have lived up to our dreams. The article began by arguing that journalism of the highest standard could not easily flourish when impeded by the restrictive practices of the printing trades unions or by the political prejudices of the typical newspaper proprietor.

We believed that we had the solutions to both these problems. As to the first, we had arranged for The Independent to be printed in plants outside London where we could share the presses with a local evening newspaper and where labour relations were good. And the editorial team embraced the new computer-based technology from the start, which cut out the old, heavily unionised “hot metal’ typesetting. Admittedly, our advantage here was short-lived for within a year or two, all our rivals had left Fleet Street and its labour practices behind and their editorial teams had jettisoned their typewriters.

As for the dominance of a “typical’ newspaper proprietor, we were proud to state that the ownership of The Independent was spread between more than 30 financial institutions and that no single investor held more than 10 per cent. In any case they were “politically neutral”. The article added that “as long as we provide a return on their investment, they will not seek to influence any aspect of our editorial judgement”. So we would be free to “make up our own minds on policy issues, to expose commercial skulduggery and to query the establishment. We would both praise and criticise without reference to a party line”. I believe we have done that. Our first chairman was Lord Sieff, who had been at the helm of Marks & Spencer for 10 years.

At first things went very well. Circulation grew strongly. The newspaper became profitable. I had almost forgotten the rule I had enunciated at the beginning: “no profits, no independence”. Until one day, just minutes after I had been discussing the newspaper’s good performance with our finance director, The Times made an announcement that was to change everything. The newspaper would conduct an experiment. It would reduce its cover price in certain parts of the country to see how much circulation would benefit. We had overtaken The Times and this was the response. In September 1993, the trial was declared encouraging. The cover price of The Times was reduced from 45p to 30p.

The effect on The Independent was drastic. Either we maintained our cover price and saw our circulation collapse. Or we matched the price cut and saw our profits disappear. In the event, we did both – and suffered both. I should have to live by the rule I had set.

We were able to refinance ourselves and take out our brilliant original backers at a small profit by inviting in new shareholders. It was at this point that I stepped down as editor. The new investors were the Spanish newspaper El Pais and the Italian newspaper, La Repubblica, both founded only 10 years earlier. Shortly afterwards the Mirror Group, followed by Tony O’Reilly’s Irish newspaper group joined the two foreign newspapers.

I had reasoned that if the new shareholders were themselves newspaper publishers, then the chances that they would interfere in editorial decisions were small and so it turned out. The Irish bought out the other shareholders in 1998 and in turn sold the newspaper on in May 2010 to its present proprietors, Alexander and Evgeny Lebedev, who also own the London Evening Standard.

But, oh, the losses! The Independent has not made a profit since 1993. The cumulative deficit up to 2010 amounted to £301m. And losses under the Lebedevs ownership currently total £69m. Yet to repeat, never once in that long period, despite losing tons of money, have any of the successive owners attempted to influence editorial coverage. I use this opportunity to express my heartfelt thanks to them for their support, and I add to their number the brave financial institutions that invested at the beginning. We used to call them affectionately, the “sporting investors”.

We started life with two big trading advantages. One was the immediate embrace of computer technology that I have already mentioned and to which I shall return. The other was editorial innovation. National newspapers had been devoid of new thinking about the product for many years because the print unions always demanded a high price for changes and managements thought the proposed improvements were not worth either the expense or the wrangling. For a newcomer operating outside Fleet Street, this was an ideal situation.

To take full advantage, the first issue promised numerous innovations. “We will carry each week a section on health, education, media and the workplace. We will display a strong bias in favour of the consumer, tackling education from the point of view of parents and students, health from the point of view of patients”.

Later we were the first to publish a magazine with the Saturday edition. But because this range of coverage has now been commonplace in national newspapers for many years, it is hard to realise how pioneering it was.

The trouble with innovations is that competitors immediately follow suit. Yet something important had happened: the need continually to innovate had become part of the newspaper’s DNA. In September 2003, it launched a tabloid version of the newspaper while continuing to publish the broadsheet so that readers could make up their own minds which format they liked. They overwhelmingly preferred the tabloid so the broadsheet was withdrawn. The circulation rose. The Times immediately followed suit and switched to tabloid format. After that, many broadsheet newspapers around the world converted.

Then in October 2010, soon after the Lebedev family acquired control, The Independent launched i newspaper. This was the most successful and significant innovation since the original launch. It was counter-cultural. For in this digital age i was still words printed on paper and, while it was cheap, it was not free. It is now well established with a circulation of more than 200,000 copies per day. And the Daily Mirror with its launch of The New Day has recently followed the example of i.

But neither these improvements, nor the initiatives taken by the rest of the national press, have served to arrest a persistent decline in circulations that has been under way for some 10 years and which can be seen in every newspaper market in the world. The same technology that enabled us to establish ourselves quickly and profitably has, 30 years later, rendered the printed edition of The Independent unviable.

The statement of purpose signed off by remarking that during the month before launch, the team had been producing fully printed “dummy” newspapers. The exercise had lacked, however, one crucial element: the readers. And the article added that it was “your relationship with us” that would “finally determine what sort of newspaper we are.” So who were we and who were you?

To describe us I will use just one statistic. The average age of the editorial team at launch was 31 years. We were refugees from Fleet Street newspapers, with a high proportion coming from The Times. Many subsequently became famous and I pick out only three – the novelist Sebastian Faulks, who was the newspaper’s first literary editor; the broadcaster Andrew Marr, originally a member of the political reporting team; and the poet James Fenton, later Professor of Poetry at Oxford University, who was a foreign correspondent. All were there on the first day.

On an edition-by-edition basis, however, we never thought of these stars as the most important people on the editorial team in spite of their obvious abilities. For the relentless strain of sending off each evening a completely fresh newspaper to the printers means that if a particular job is done badly, it quickly affects the rest of the operation. In this light, every single member of the team is equally valuable.

From the bottom of my heart on this sad occasion, the publication of the last print edition of The Independent, I thank the hundreds of journalists, perhaps over a thousand, who have, in their different ways, contributed to its success. Now, condemned to innovate as we have always been throughout our history, we will in future deliver our editorial coverage by means of three channels, through the iPad daily edition, through the online site updated throughout the day (independent.co.uk) and through i.

As to you, dear readers, I am clear who you are. You are independent minded. I have never analysed you by gender, age, class, education, wealth and the other characteristics beloved of advertisers for whom this information is commercially valuable. To say that somebody is independent minded indicates no particular profile. It simply defines an attitude. You immediately recognise the independent-minded when you meet them.

These are the people we have wished to serve. I thank you, too, for your interaction with us and for your encouragement over the years.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies