André Courrèges: Fashion designer whose stark, white Space Age miniskirts and catsuits helped define the Sixties

Courrèges looked into the future and saw his woman de-sexed, disciplined and monochrome

Two designers dressed the Sixties: Mary Quant in London and André Courrèges in Paris. While Quant led her woman into the playground dressed in a flannel gymslip and a black polo neck, Courrèges orbited his into outer space wearing a stark white catsuit. She reached the Moon with Courrèges in 1964, five years before Neil Armstrong’s small step in July 1969.

Courrèges looked into the future and saw his woman de-sexed, disciplined and monochrome. His strict clothes were arrestingly sexy. To Courrèges woman was not an amalgam of curves but a series of flat planes. On his square-cut clothes the junction of each plane was defined by a welted seam – this sufficed as decoration.

His antiseptically clean-cut, Space Age clothes looked as if they had been designed with a slide rule and cut out with a scalpel. Dressed in either a very short skirt, or, better still, trousers, Courrèges’ modern adventuress was free to move fast.

Courrèges’ vision was the sum of his background. He trained as a civil engineer before taking up fashion and textile design in Paris. He was also passionate about the Basque regional sport of pelota, which he played with considerable skill and agility. The conjunction of precise, architectonic construction and sporty freedom summed up his fashion vision.

What made that extraordinary vision work was the fact that he was a gifted and meticulous craftsman. For 11 years, from 1950 to 1961, he trained as a cutter in the most prestigious and exacting couture house in the world, Cristobal Balenciaga. From the that house he emerged with two essentials that would determine his life as an haute couturier; the skills of a master tailor and the love and inspiration of his future wife, Coqueline, whom he met while working alongside Balenciaga.

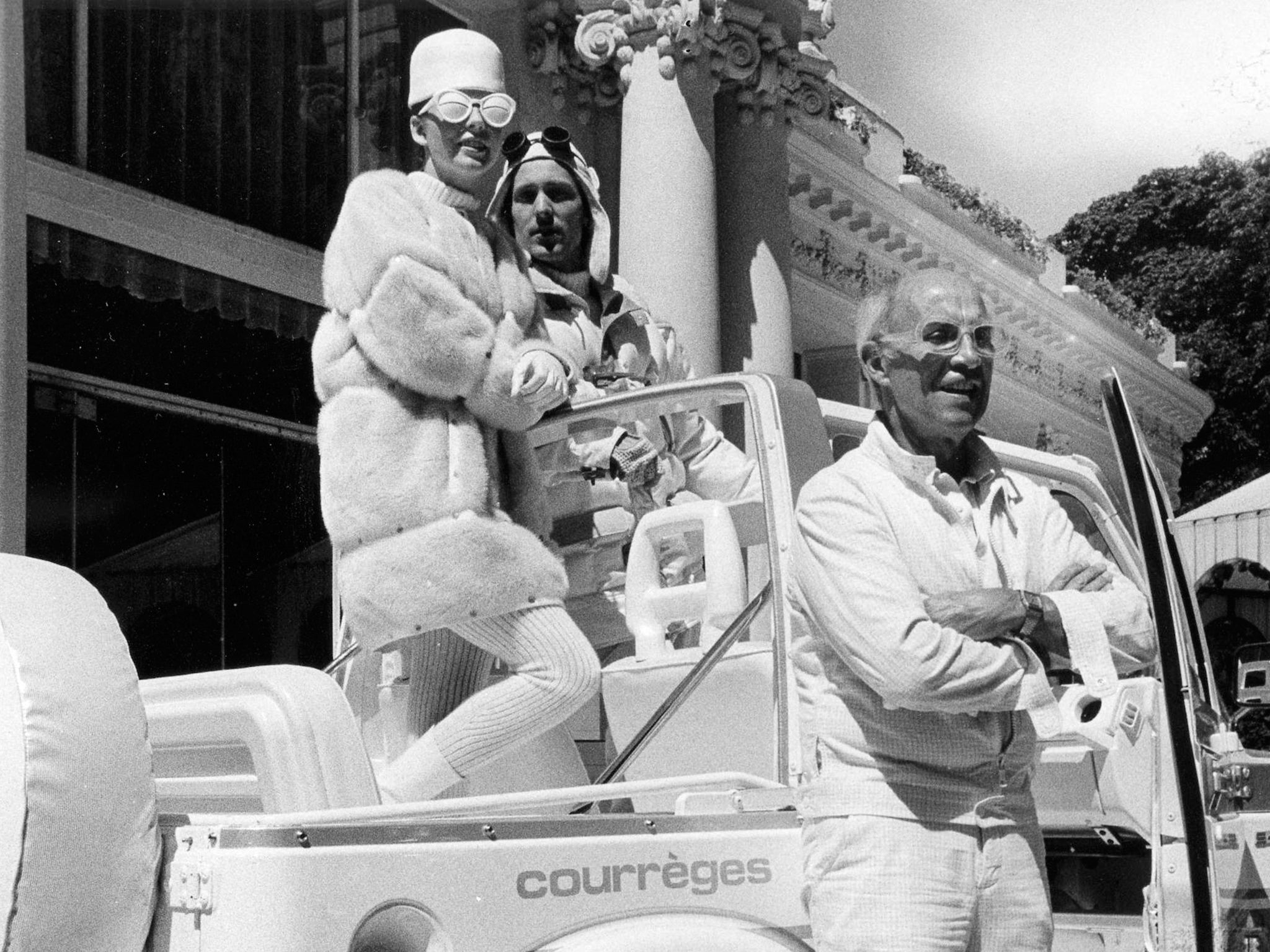

Courrèges opened his own couture house in 1961 and worked from an all-white studio dressed in sports jersey, trousers tucked into kid boots and matching glasses; a monochrome winter-white or sugar-almond pink maestro.

Along with Marc Bohan, then designing for Dior, he was credited with creating the first couture minis; they had already reached the London streets, via art students, thanks to Mary Quant. Initially Courrèges’ style was pure Balenciaga, only abbreviated. He showed neat, strict tailoring in monochrome colours or bold black and white houndstooth checks supplied by the innovative textile house, Nattier.

The vital role of textile designers and fabric houses is invariably unsung in the history of fashion. In fact, there is a strong sense of collaboration between couturiers and fabric designers, for innovative materials often stimulate a designer’s imagination and suggest themes and new possibilities. Nattier (a name adopted by the Italian firm of Azzaro to overcome the prejudice of Parisian couture against foreign manufacturers) introduced Courrèges to triple gabardine.

This heavy cloth, which could be moulded like Plasticine, was directly responsible for the look. Because of its weight, the clothes had to be short and close to the body. Without it, Courrèges could not have achieved his Space Age look.

The look had a mind-blowing impact when he launched his Space Age collection in the spring of 1964. The square shapes were so uncompromisingly square that he was dubbed the “Le Corbusier of Paris Couture” by Women’s Wear Daily. His models, dressed in cardboard-stiff shifts, trouser suits and tabards, walked out on to the runway and transported the audience to an other galaxy. Helmeted in white, eyes shielded behind opaque white sunglasses, hands covered in tight white kid driving gloves, legs sheathed in white kid boots with cut-out toes, the models played out a child-like rendition of an urban astronaut.

Marit Allen, then a young journalist working for British Vogue, was spellbound. She rushed to a pay-phone and called Beatrix Miller, her editor. ‘‘You’ve got to scrap the entire issue and just show Courrèges,” she pleaded. “This is the future of fashion, nothing else matters,” she insisted. The more measured Miller featured the clothes extensively, but not exclusively.

My mother remembered attending the Prix de L’Arc de Triomphe at Longchamps in October 1964. “The arrival of the Courrèges mannequins,” she recalled, “stepping from the usual limousines, seemed more like an outer-space landing and was indeed the most exciting fashion innovation I had experienced for quite a long time. It was mind-blowing female freedom because we were still confined by the unbending propriety of previous decades. His look, like ours, was neat, tidy and controlled, but his promised freedom, not restriction. Like most temptations it was desirable but frightening!”

Courrèges’ vision worked because he caught the optimistic euphoria of the times, epitomised by the Space Race, and because he played up this futuristic vision to the hilt. The future was white, scientific and young, and so were Courrèges’ clothes. Gloves, hats, boots, belts, make-up, all were honed down to Space Age simplicity by Courrèges and finished off with a silver wig, which was worn with the same nonchalance as frosted pink lipstick.

His Space Age look evolved and was juxtaposed with a de-frilled Baby Doll look consisting of round-collared shifts in white or sugar almond-coloured guipure lace, baby caps fastened under the chin, white knee socks and flat white baby sandals tied over the instep. Superficially they may have seemed “ingenue” but the customer who wore these couture togs was as mondaine as one could be. Her tongue-in-cheek innocence was thought wildly amusing by a generation that was playing with the Pill, free love and iconoclasm for the first time.

Space Age was followed by Bare as you Dare, when Courrèges showed the barest back in Paris – a white lace evening catsuit, modestly covered up in front and caught only at the back of the neck from where it plunged naked and sun tanned to the other cleavage. By 1967 Courrèges’ bare midriffs, bare backs and see-throughs had prompted Coty cosmetics to introduce body paint.

High fashion is not protected by patents, and within a couple of years Courrèges’ look was being copied around the world, invariably badly because few understood the importance of triple gabardine. Floppy copies failed, aesthetically if not commercially. In disgust he sold his house to L’Oreal in 1965 and worked for a few private clients.

But by 1967 he had come up with a better solution – to copy himself. He launched three ready-to-wear lines: “Prototype”, “Couture Future” and “Hyperbole”. Exploiting his engineering skills, his ready-to-wear gained the reputation for being the most meticulously produced in Paris. I still wear my mother’s black triple gabardine trapeze dress from the autumn-winter 1967 collection; it’s as band-box smart and iceberg-lettuce crisp as the day she cast fear aside and stepped into it.

Diversification into menswear, scent and accessories ensured Courrèges’ financial survival. In 1973 he went into menswear and opened his first separate menswear boutique in Paris in 1974. Boutiques followed in Europe, the Far East, the Middle East, the Americas and Australia. He also designed computers, cars, scooters, telephones, domestic appliances, children’s clothes and toys. In 1971 he produced his first house perfume, Empreinte, followed by Eau de Courrèges and, in 1977, a men’s fragrance, Amerique, Courrèges in Blue in 1983, and Sweet Courrèges in 1993. From 1970 he was the architect for his own boutiques.

Courrèges’ period of fashion supremacy was short but vivid, spanning five years, from 1963 to 1968. Once the hemline had fallen and hippy retrospection replaced optimistic futurism, his look moved into a fashion cul-de-sac. But that look, like that of Jean Muir and Madam Gries, though immutable, became a fashion classic. It was a triumph of good design over novelty.

In his final decades Courrèges could still be seen in Paris wearing his bubble-gum pink and winter-white sports separates tucked into Space Age boots. He continued to look more modern, more futuristic and more optimistic than the grey- flannelled bureaucrats and businessmen past whom he walked on his way to his all-white studio.

He invited a younger design optimist and futurist whom he admired, Jean-Charles de Castelbajac, to become the design director of his house, which left him more time to paint, sculpt and dream about his all-white future. In an industry where lazy designers keep rehashing the past in a decadent self-glorification of its own history, Courrèges, a determined futurist and an eager innovator, stood firm and tall.

André Courrèges, fashion designer and architect: born Pau, France 9 March 1923; married 1967 Cocqueline Barriere (one daughter); died Neuilly-sur-Seine 7 January 2016.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks