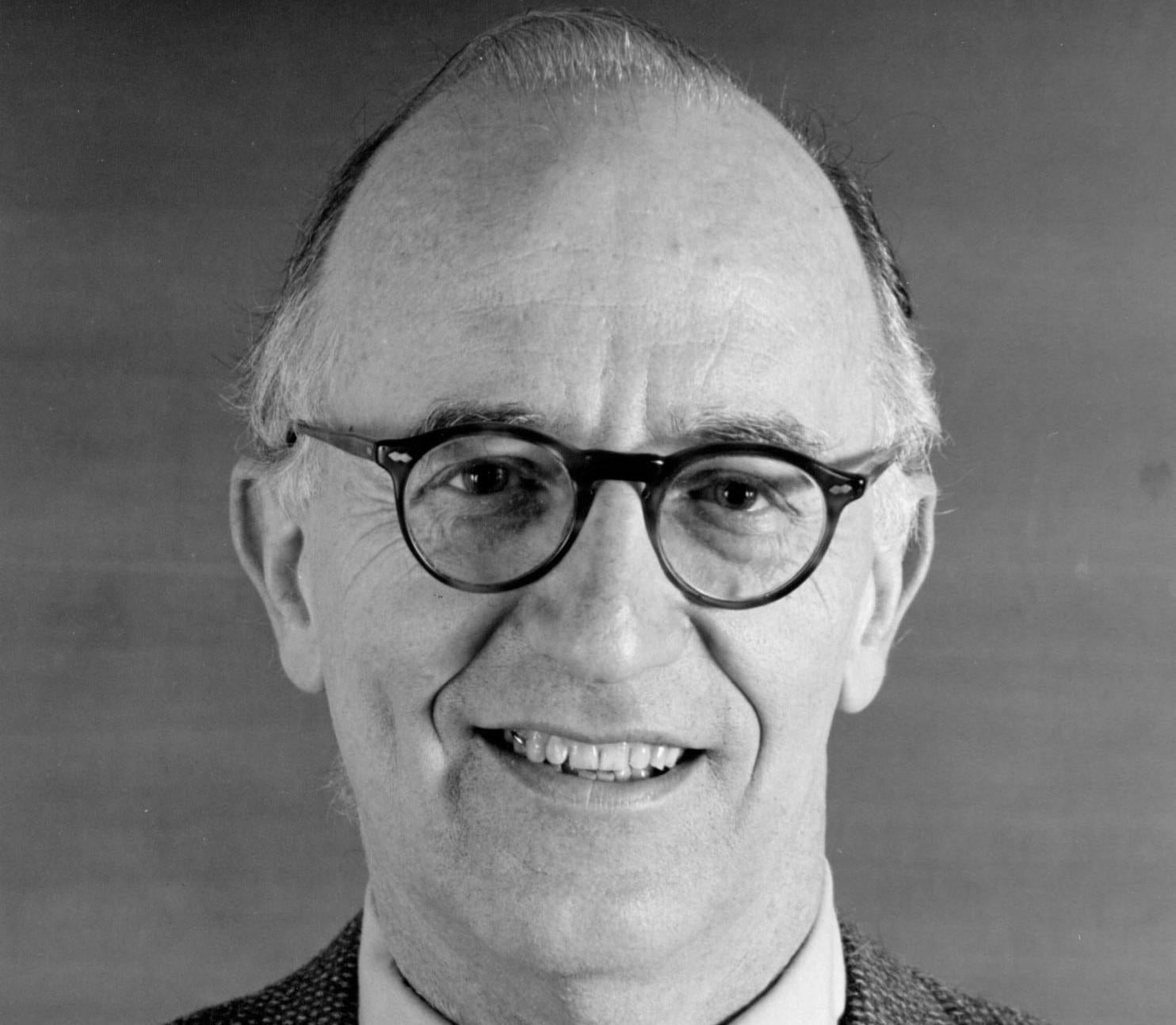

Edward S Herman: Scholar whose radical critiques of US media characterised the fake news caricatured by Trump

Noam Chomsky, co-author of ‘Manufacturing Consent’, told The Independent Herman was an ‘inspiration’ to those following in his footsteps in media studies, ‘exposing hypocrisy and lies’

In 1973, during the final throes of the Vietnam War, publisher Claude McCaleb was summoned to the office of William Sarnoff, his boss at Warner Communications in New York. According to McCaleb, an incensed Sarnoff attacked him for one of the works he was about to publish, calling it “a pack of lies”. Sarnoff announced that the book would not be released, and ordered the destruction of the Warner catalogue listing it.

The book was Counter-Revolutionary Violence: Bloodbaths in Fact and Propaganda, a blistering critique of US foreign policy in Vietnam and elsewhere. The authors were Edward S Herman and Noam Chomsky, neither of whom cared to ingratiate themselves with America’s media elite.

Herman, who has died aged 92, would never attain the fame that befell his frequent co-author Chomsky. But he gained widespread recognition in financial academia for his illuminating studies of power and money, and on the radical left for his persistent deconstruction of the propagandistic filters through which mass media perceive, and present, the world.

His most influential work, first published in 1988 and re-edited twice to great success, was Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media, again co-authored with Chomsky. By analysing the structure of American journalism – its ownership, business model, ideology, sources, and the negative feedback it receives – Herman and Chomsky were able to draw out why the mass media performs the way it does, and what propagandistic interests it serves. It drew on case studies to show how market forces, internalised assumptions and self-censorship function to support the system in place, even without overt coercion.

Three decades on, the propaganda model developed in Manufacturing Consent remains as subversive as it was then. Today, it provides a fierce rebuttal of the claim that “fake news” is a new phenomenon – and that the mainstream press is immune to it.

After Herman’s passing, Chomsky, who was close friends with him for 50 years, told The Independent: “He was an inspiration to those lucky enough to know him personally but also to countless others who have been following in his footsteps in institutional analysis, media critique, exposing hypocrisy and lies, and to the many who recognise him as providing a model of integrity and understanding.”

Edward S Herman was born in 1925 in Philadelphia. A “Depression baby”, as he called himself, Herman’s early outlook was formed by his parents, who were “good liberal democrats”, cousins of his who were more radical, the economic crisis of the 1930s and the events of the Second World War. “All of this made me into a left-winger,” he said.

After the war he went to the University of California in Berkeley to pursue a PhD in economics. He was drawn to Berkeley by such scholars as Robert A Brady, who had written of the propaganda and economic mechanisms of Nazism.

In 1958, he joined the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, an institution he would remain affiliated with in one way or another for the rest of his life. Over the next 15 years he contributed to group studies of financial institutions, with him serving as the resident specialist in issues of power and control. This research culminated in his 1981 book Corporate Control, Corporate Power, in which he investigated the ownership and control of America’s large corporations.

The 1980s were a particularly prolific time for Herman, during which he published five books. The final one, Manufacturing Consent, was largely inspired by Herman’s earlier financial scholarship. Such was Herman’s contribution to the book that Chomsky insisted his name appear first on the cover, contrary to the pair’s habit of alphabetic listing.

In the following years, Herman continued his critical study of the mainstream press. In the first half of the 1990s, he edited and wrote profusely for Lies Of Our Times, or LOOT, a weekly journal publishing sharp takedowns of articles appearing in The New York Times. The publication garnered 5,000 subscribers, he said. In an especially incisive piece, Herman attacked media coverage of the Reagan administration’s decision to pull the US out of Unesco. He argued that the mainstream press, and in particular The New York Times, had accepted US charges against Unesco, and ignored the credible alternative view that Reagan was acting to safeguard US unilateralism.

By the late 1990s, Herman had launched InkyWatch, an online journal following the same model of regularly critiquing a particular newspaper – in this case the local Philadelphia Inquirer. “I never had the resources to build it into something big,” he said, “although I still think this is a great idea – it should be done for each local monopoly paper and maybe TV station.”

The conclusions of Herman’s media criticism were not always convincing. But his best work displayed a thoroughness of research, and a clarity of thought, reminiscent of A Test of the News, Walter Lippman’s classic 1920 study of The New York Times’s coverage of the Russian Revolution. That study found that, as those historic events unfolded, the newspaper published what it wished to see, rather than what was.

Through his various projects, Herman forged links with various like-minded thinkers, who formed networks that shared information and insights not readily available in the mainstream press. In Notes to Eternity, a recently released documentary on the Israel-Palestine conflict, Chomsky referred to these networks as the “dissident margins” of academia. Herman was a prominent, if unassuming, figure on those margins.

Some of his other work, especially relating to genocide, caused severe backlash from parts of both the right and the left. The Politics of Genocide, which he co-authored in 2010, argued that the West made excessive use of the word ‘genocide’, and selectively applied it to fit its political agenda. His writings on Cambodia, Srebrenica and Rwanda in particular were denounced by some as “genocide denial” and “revisionism” – claims he always rejected.

But Chomsky, being the more famous of the two, often took more of a pounding than Herman did. Once asked whether he ever faced harassment from colleagues because of his writings, Herman said: “I did get occasional little anonymous letters through intramural mail, but there were a lot of Wharton people who thought that what I was doing was valuable.”

Herman was known to be generous to fellow scholars and activists, gifting the writer Diana Johnstone her first computer, in the 1980s, taking time to foster interns at LOOT, and supporting many in their research.

In his early years, Herman regularly protested outside the White House and wrote numerous activist letters, but that slackened off as he got older. Overall he was more comfortable in his Wharton office, surrounded by reams of research papers, simply writing. “I was an activist only to a moderate degree even in my physical prime,” he said. “I’ve always been mainly an ivory-tower activist hurling my missives in support of on-the-ground activists.”

In later life Herman continued to write, though at a milder pace. “I start in the morning, not too early,” he said, “and work sporadically till it’s time to drink a glass of wine about 4:30pm. From then on, I take it easy.”

His last published piece, which came out in July, denounced the mainstream American press for succumbing to an anti-Russian frenzy. Herman had lost none of his verve.

At his old house in the leafy Narberth suburb of Philadelphia, he would often feed stray cats. He loved the music of Haydn, Mozart and Scarlatti, the last of which he especially enjoyed playing on the piano. Good French food was his only known self-indulgence. He is survived by his second wife, Christine Abbott. His first wife, Mary Woody, died in 2013, after 67 years of marriage.

Once asked about his dedication to scholarly research, over the kind of on-the-ground work favoured by other activists, he said: “I believe we should let a thousand flowers bloom and that it is fine for a few flowers to concentrate on writing critical stuff.

“Everybody doesn’t have to do the same thing.”

Edward S Herman, media critic and scholar of finance, born 7 April 1925, died 11 November 2017

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments