Frances Oldham Kelsey: Scientist who blocked the sale of thalidomide in the US, saving countless unborn children from its dire effects

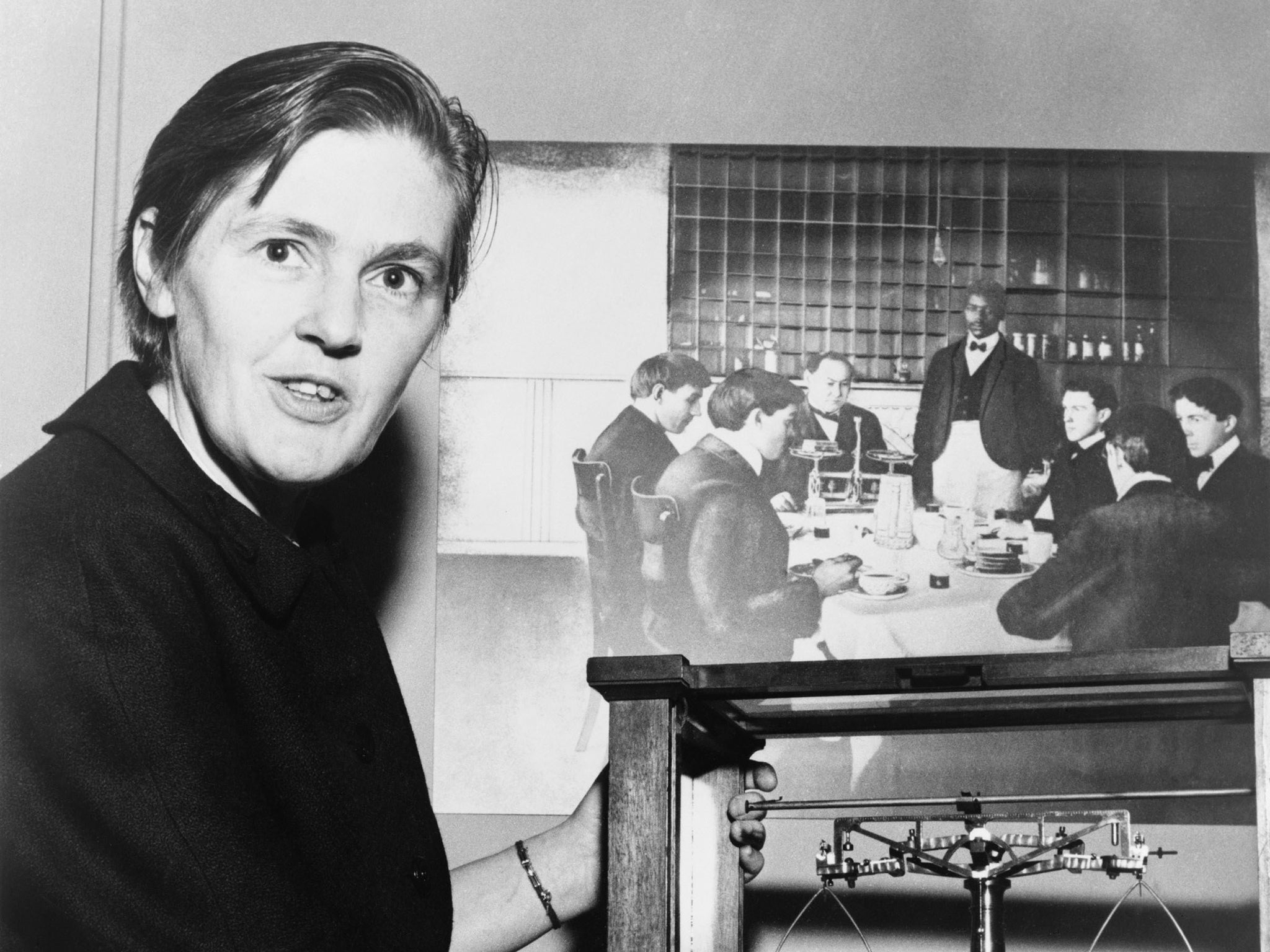

President John F. Kennedy presented Kelsey with the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service

Dr Frances Oldham Kelsey was the pharmacologist whose courage and determination protected pregnant women and their unborn children from the effects of thalidomide, by ensuring that the drug never obtained approval in the US.

Frances Oldham was born in 1914 on Vancouver Island, British Columbia and attended Victoria College. She studied pharmacology at McGill University, Montreal, obtaining her bachelor’s degree in 1934 and her master’s the following year. In 1936 she joined the team of Dr Eugene Geiling, who had founded a new pharmacology department at the University of Chicago.

She soon became involved in research into 107 deaths caused by a sulfonamide medicine. Kelsey and her team established that the fatalities were related to the use of diethylene glycol as a solvent. She later worked on finding a synthetic cure for malaria and discovered at this time how drugs are able to pass through the placenta into the unborn child.

Kelsey began work with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1960, one of a team of only 11 doctors then working on the safety evaluation of new pharmaceuticals. The FDA had originally been established to respond to food contamination incidents and was not well equipped to deal with the post-war boom in drug research. Mandatory safety-testing had been in place since 1938, but even so, the FDA’s responsibility had been to prove that a drug was unsafe, rather than that it was safe.

During her first month at work, Kelsey was assigned the task of evaluating the safety of thalidomide, a drug developed by the German company Chemie Grünenthal and marketed since 1957 for morning sickness and insomnia. Thalidomide was already being sold in the UK by the Distillers Company, under the brand Distaval, and had been licensed to the US company Richardson-Merrell as Kevadon.

Richardson-Merrell were pushing aggressively to have the drug on the market within a year. Kelsey recalled: “At that time, we had 60 days after receipt of the NDA [New Drug Application]... If we had no objection or if we forgot that the 60 days had elapsed, the drug automatically became approved and the company could put it on the market.”

“The claims made in the NDA for thalidomide were too glowing,” Kelsey wrote in a later memoir. “That was the initial thing that led us to require more substantiation. The claims were just not supported by the type of clinical studies that had been submitted in the application.”

Prompted by the company’s claims and her doubts about their accuracy, Kelsey requested data proving the drug’s safety and efficacy. The company refused to provide any test results, but remained insistent, making six requests demanding that the drug be approved. But Kelsey stood firm and refused to approve thalidomide for use in the US.

FDA historian, John P. Swann, said, “It’s fascinating to see how many letters and communications went back and forth. She was asking for additional data, and what they were sending was, in her eyes, insufficient to answer the questions she was raising. She was increasingly pressured by the sponsor to get the drug approved. She didn’t back down.”

In November 1961 the German newspaper Welt am Sonntag reported on the link between the use of thalidomide and deformities in children. Within 10 days, thalidomide had been removed from the market. Enquiries and lawsuits began. The drug was also withdrawn in the UK, but not before some 2,000 babies had been born with thalidomide-induced impairments, including shortened limbs and extra fingers and toes.

In July 1962 the Washington Post ran the front page headline “Heroine of FDA Keeps Bad Drug Off Market”, together with a report by the journalist Morton Mintz on the harm which had been caused by thalidomide. By October, and in considerable part due to Kelsey’s work, President John F. Kennedy signed into law the Kefauver Harris Amendment. The new regulations required that pharmaceutical companies operating in the US prove the efficacy of their products and advertise accurate information about them and their potential side-effects.

Kennedy presented Kelsey with the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service, the highest recognition possible for a civil servant. She continued to work for the FDA until her retirement in 2005, aged 90.

Dr Ruth Blue, secretary of The Thalidomide Society, which campaigns on behalf of those affected, told The Independent: “Frances Kelsey’s dogged determination to rebuff Richardson-Merrell’s pressure to authorise the distribution of thalidomide in the US has changed the course of thousands of US lives.

“Based on the scale of effects experienced in the UK and Germany, it is reasonable to surmise that there could have been well over 16,000 thalidomide deaths and 11,000 thalidomide survivors in the US. Her enduring legacy also encompasses the formulation and implementation of stricter regulation of the pharmaceutical industry.”

Frances Kathleen Oldham Kelsey, pharmacologist: born British Columbia, Canada 24 July 1914; married 1943 Dr Fremont Ellis Kelsey (two daughters); died London, Ontario, Canada 7 August 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments