George Miller-Kurakin: Anti-communist campaigner who inspired Conservative activists during the Cold War

Intellectual and visionary, liberal and anti-Communist, George Miller inspired a generation of Conservative activists in the 1980s, when the Soviet Union seemed impregnable. His operations were so extensive that few of his associates knew the full picture.

He created the Russian Research Foundation and its Soviet Labour Review. He was a researcher and adviser to Anglo-American think-tanks, including the Institute for European Defence and Strategic Studies and the Adam Smith Institute. Later he worked with Anatoly Chubais, the Russian privatisation minister, while Yeltsin's reformers briefly held sway.

For Miller the demise of Soviet Communism was an absolute certainty, provided that the West remained strong. His vision was tempered with patience and humour. He would liken the regime to an elephant, repeatedly stung between the eyes by a mosquito. The insect would be brushed aside time and again – yet, one day, without warning, the elephant would roll over, stone dead, with its feet in the air. Miller lived to see it happen; indeed, he helped to make it happen.

George Miller was born in Santiago in 1955. His father Boris, an engineer, had migrated from Serbia where his own father, a White Russian émigré, had been murdered by a political gang in front of the family. In Chile Boris met and married Kira Kurakin, of the celebrated St Petersburg family, and in 1959 the family moved to Frankfurt to work full-time for the counter-revolutionary National Alliance of Russian Solidarists. Boris then became its representative in London.

The young George attended Bromley grammar school, Queen Mary College and Essex University – from which he graduated with an MA in Soviet Government and Politics in 1979. The Miller-Kurakin family were committed democrats, and it was as a member of the Young Liberals that Miller accepted an invitation to speak to a conference in Valencia about Soviet violation of the Helsinki Accords.

The European Democrat Students, a federation of Conservative student movements, heard him describe how human rights could be used as a lever to destabilise Communist dictatorships. His effect on the audience was electric. As radicals for change in their own countries, they were captivated by Miller's vision of a democratic Russia. Charismatic, pragmatic and persuasive, he signed them up to his cause. The result was East European Solidarity Youth (EESY), whose activists included the future MSP, Brian Monteith. Couriers carried uncensored mail and anti-Communist literature into Soviet Bloc countries and brought information out – a lifeline for hard-pressed dissidents. Periodically, the youngsters were caught and expelled, making good use of the resultant publicity.

"Before George, we made speeches to each other and took on the Left in students unions; but this was the real thing," one of them recently recalled. This was also the height of the second Cold War, with Solidarity yet to emerge and loosen the Soviet grip. Miller co-wrote a Bow Group paper entitled Prelude to Freedom, and leaflets in the name of his Association For A Free Russia were given to ministers, who looked on them with disdain. The establishment viewed the USSR as a permanent superpower. But Miller never doubted that the system was doomed.

Its downfall depended on Nato remaining strong; so, from 1981 until it passed its peak, Miller worked closely with opponents of Western unilateralism. When the tiny Moscow-based "Group for Establishing Trust between the USSR and the USA" was cited by some as evidence that a peace movement could be built behind the Iron Curtain, Miller sent Young Conservatives with anti-nuclear leaflets to test this on the Moscow metro. One was caught and kicked out in a blaze of publicity. Miller also arranged the visit to London of Oleg Popov, one of the group's advisers, who promptly told the media that, while support from CND and END was appreciated: "Unilateral disarmament is no answer. It is nonsense and potentially dangerous".

Miller never sought personal publicity, but never minded taking a lead. With the Coalition for Peace Through Security, he spent a year planning a lively reception for the 1986 Copenhagen "Peace Congress" – the first set-piece effort in a Nato country by the Soviet-controlled World Peace Council (WPC) since its abortive Sheffield Congress of November 1950.

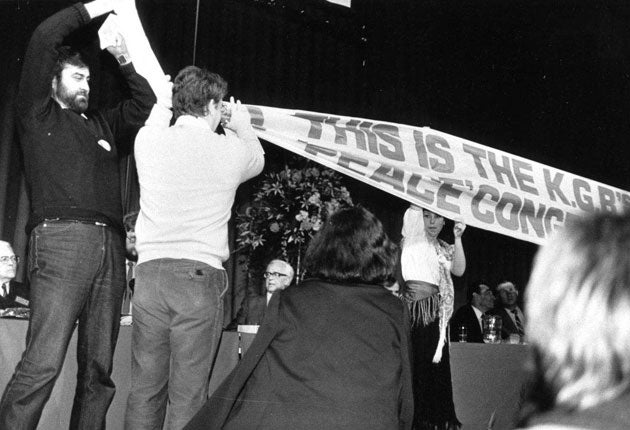

The USSR spent a great deal of hard currency staging the Copenhagen event. It opened with Miller and two others unfolding a giant banner on the platform which declared: "This is the KGB's 'Peace' Congress". On the second day, pictures of him being roughly handled dominated the Danish press. On the final day, dozens of his activists (who had somehow acquired delegates' credentials) mounted a protest against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. The ensuing mayhem achieved worldwide media coverage, throwing new light on the WPC's favourite catch-phrase – "The Fight for Peace".

Miller was both compassionate and courageous. Exploiting a distant Muslim family link, he entered Afghanistan to negotiate the release of captive Russian soldiers who had survived by converting to Islam. When others stood by, he was ready to act – saving a young woman who had slipped from a platform by hauling her to safety as a train moved off. He remained, above all, an inveterate optimist with a magnetic personality. A pillar of the Russian Orthodox Church, he was mystical, spiritual, selfless and humane. A hero of our times.

Julian Lewis

George Miller-Kurakin, anti-Soviet campaigner: born Santiago, Chile 25 April 1955; married 1986 Lilia Zielke (one son, one daughter); died London 23 October 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments