Patrick Edlinger: ‘The god of free climbing’ who became a national hero in France

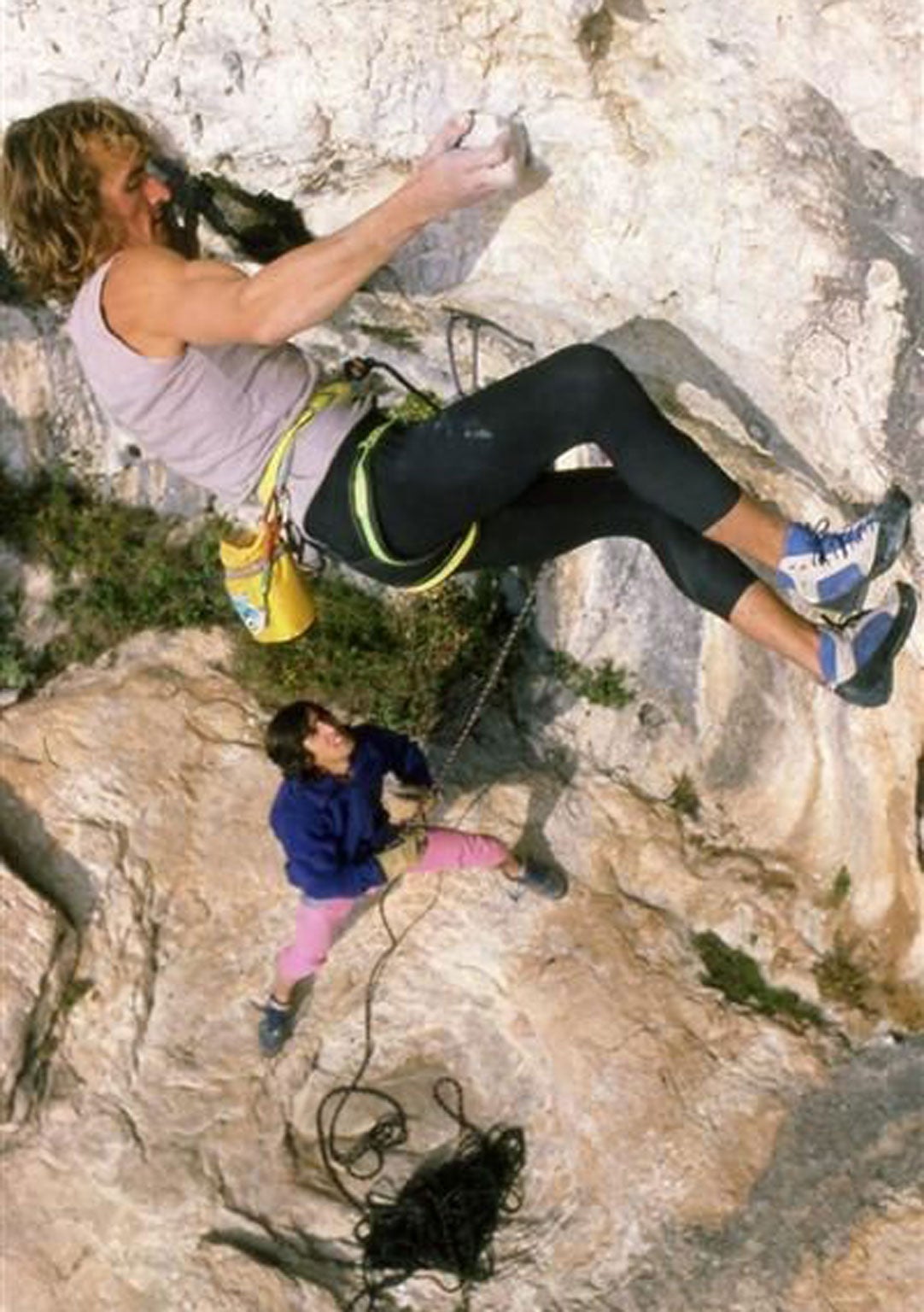

Patrick Edlinger, who has died aged 52 after falling down stairs at his home, was often described as “the God of free-climbing”. Overcoming sheer vertical rock faces and horizontal overhangs, often without safety ropes or even shoes, he was widely known in France simply as “le Blond,” and among his English-speaking fans as “the blond Adonis”.

His exploits helped lead to the craze for artificial rock-climbing, now popular everywhere from sports clubs to luxury ocean liners, although he himself rarely used pre-placed bolts. If he ever needed bolts, he carried one or two with him. Calling himself a “minimalist climber,” he relied on strong fingers and toes, his core muscles, super-flexible legs and fine balance to overcome rock faces most of us see only in our nightmares. Hanging by the fingertips from a horizontal overhang, most of us would see but one option – to pray and let go. Edlinger, however, could swing his feet above his torso and find a grip with his toes or even heels. “It’s a form of yoga,” he liked to say.

Edlinger was a French national hero in the 1980s and ’90s, soon to become a worldwide phenomenon through TV films and documentaries about his exploits in what the French call l’escalade libre, or free rock-climbing. When his wife announced on 16 November that he had been found dead at home earlier that day, the news spread like wildfire on climbing websites and led to tributes in major French newspaper the following day, sending the international rock-climbing fraternity into mourning. Friends said he had in recent years suffered from an alcohol problem although it was not clear whether this contributed to his domestic fall.

He was perhaps best-known for climbing the sheer 1,500ft vertical cliffs of the Verdon Gorge, south-east France’s smaller but still impressive equivalent of America’s Grand Canyon. There he usually climbed topless, wearing only flimsy running shorts, his main prop a leather chalk-sack to give grip to his fingers and toes, and a Rambo-style bandana to contain his long blond hair. He came to fame in the 1980s after the film-maker Jean-Paul Janssen captured his exploits in two documentaries – La Vie au bout des Doigts (1982, later broadcast on the National Explorer Series in the US as Life by the Fingertips) and Opéra Vertical (1986) – films which helped put him, and France, at the forefront of modern rock-climbing.

The former film, which will take your breath away but barely took his, saw him climbing the limestone cliffs at Buoux in south-east France’s Vaucluse region, which now attracts rock climbers from around the world. In the latter, he was climbing the walls of the Verdon Gorge above the stunning turquoise Verdon river.

He went on to win some of the earliest rock-climbing events, including at Bardonecchia and Arco in Italy in 1985-86 and, in 1988, the very first international competition in the US, on a man-made wall on the side of a hotel in the ski resort of Snowbird, outside Salt Lake City, Utah. He was the only climber to reach the roof, where he was magically but appropriately lit by a shaft of non-man-made sunlight, a moment no one present could ever forget. He famously turned to his hero in the audience on a platform nearby, the American climber Henry “Hot Henry” Barber, a legendary climber from the previous generation, and yelled: “That was for you!” Edlinger’s friend and Algerian-born French compatriot, Catherine Destivelle, won the women’s event at Snowbird and went on to be the first woman to ascend – solo – the daunting north face of the Eiger in Switzerland in 1992.

Edlinger was also a driving force behind rock-climbing at Céüse in France, whose grey limestone rock faces, split by a famous waterfall, are now considered among the hardest in the world by sports climbers. It was Edlinger who created what he called “spicy” sports routes at Céüse by placing bolts – almost impossibly distant from one another – up its famous crags. Asked years later why he didn’t place more bolts to make the climbs more user-friendly, he replied: “We didn’t have enough money for more bolts in those days. We had to ration them.”

After a near-fatal fall in 1995 from a steep-sided calanque, or cove, in southern France, after which he suffered brief cardiac arrest, Edlinger slowed down somewhat and helped found the magazine Roc ’n Wall, for a time a kind of bible to the growing European “free solo” climbing movement. He settled close to his beloved Verdon Gorge, where the gîte which he ran with his Slovakian-born wife Matia, Gîte l’Escales in La Palud-sur-Verdon, became a starting-point for rock climbers from every continent.

Patrick Edlinger was born in 1960 in Dax, south-western France, best known for its mud treatment for rheumatism, something he himself, perhaps gratefully, never got round to needing. He was barely a teenager when he started climbing and, after earning his first wages as a lorry driver, decided he loved cliffs more than highways. Such was his image in France that, after his death, the French minister of sports and youth, Valérie Fourneyron, said: “Patrick was a pioneer in France for free climbing at a high level, a man who had a thirst for the absolute challenge. He refused to compromise and disdained conventions. He dedicated his life to his passion – climbing. He was the first to establish climbing as a true discipline of live art, paving the way for many to climb with respect for nature.”

Patrick Edlinger is survived by his wife Matia and their 10-year-old daughter Nastia.

Patrick Edlinger, rock climber: born Dax, France, 15 June 1960; married (one daughter); died La Palud-sur-Verdon, France 16 November 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks