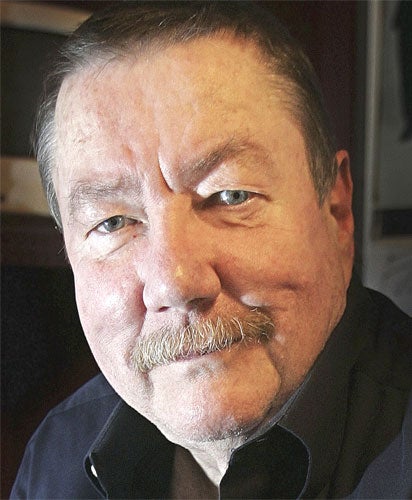

Robert B. Parker: Crime writer best known for the 'Spenser' series of novels

For those of us who cut our teeth on Dashiell Hammett's Sam Spade and Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe, it was a very long wait until the right knight-errant came along to go down those mean streets with. In the 1960s I thought it might be Bart Spicer's Carney Wilde or Ross MacDonald's Lew Archer, and in the '70s I was seduced for a while by John D. McDonald's Travis McGee, but good though they all were, they just weren't quite.

And then in 1974 came The Godwulf Manuscript. The writer was Robert B. Parker, the private eye was no-first-name Spenser, the opening sentence was: "The office of the university president looked like the front parlor of a successful Victorian whorehouse." And I was hooked.

One by one I found all the Spenser novels and devoured them in single-sitting heaven. It came as no surprise to me when the Mystery Writers of America voted Promised Land the best mystery novel of 1976, but what did surprise me was that the author was virtually unknown in England – in fact, his most recent books hadn't even found a publisher. So I wrote and told him I'd like to do something about it. He gave me an update: Piatkus Books was going to publish Looking for Rachel Wallace, and Mills & Boon were taking on the earlier Spensers to launch a new paperback imprint called Keyhole Crime. And I took it from there.

Smack in the middle of a career as a thriller writer myself, I knew a bit about the publishing business, so I got on to Judy Piatkus and Mills & Boon's Heather Jeeves and invited them to become founder members of a new and hyper-exclusive club: the RBPFBDSWSRCCOE ( 'Robert B Parker for Best Detective Story Writer Since Raymond Chandler' Club of England). My plan was to enrol everybody who was anybody in the crime-writing/reviewing biz – ranging from pals like Bob Ludlum and Dick Francis, John Gardner and Ken Follett to key book columnists in national and regional newspapers, and enlist their help in spreading the word about this terrific writer.

A year or so later Penguin took him on, but it wasn't a good fit. Bob came over to do TV, radio and newspaper interviews, plus a series of writers' workshops with his friend Stephen King, at one of which, I remember, as he mentioned Moby Dick, he took time out to patiently "explain" to Steve that it was a novel, not a disease. When I told him about the RBPFBDSWSRCCOE and what I was up to, Parker shook his head sadly, put his hand on my shoulder, and gravely informed me I was clearly, certifiably mad. Of his prospects in the UK he said only, "If it weren't for you, I'd begin to suspect the Jerries won the war."

In 1985 Spenser became a television series, Spenser: For Hire, starring Robert Urich, which kick-started a series featuring Spenser's cool, amoral, dangerous sidekick, A Man Called Hawk. Meanwhile, under the guidance of Seymour "Sam" Lawrence at Delacorte Press in New York, Parker began to branch out – notably in Wilderness, a Hemingwayesque novel that didn't feature Spenser, Love and Glory, a romance that took its cue from the song "As Time Goes By," and Three Weeks in Spring, a touching memoir of his wife's successful battle with breast cancer.

There was even a double-length Spenser, A Catskill Eagle, which persuaded some of us, and perhaps Parker, that twice as much of his Jewish-therapist squeeze Susan Silverman wasn't necessarily twice as good. Spenser's problems with Susan in that novel echoed the Parkers' marriage (after a period of separation they lived in the same house again, but on separate floors). It's almost a cliché to add that all his books are dedicated to his wife Joan (who he claimed to have first met when she was three).

By 1989, when Phyllis Grann persuaded him to join Putnam ("for zillions" as he put it) Parker had become seriously Big Time. And went on to become one of the bestselling writers of his generation, just as, I believe, he had always known he would. I say that because Parker had – while working variously as a technical writer, in advertising, as film consultant, teaching fellow, instructor and assistant professor, not to mention a two-year stint as a GI in Korea and getting his bachelor's in 1954 at Colby College, his masters in 1957 and PhD in 1971 at Boston University – signalled clearly where he was going with his dissertation, "The Violent Hero, Wilderness Heritage and Urban Reality: A Study of the Private Eye in the Novels of Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler and Ross MacDonald."

Having formed a production company with his wife in 1988, Parker – when not kicking around projects with the likes of Steven Spielberg, Michael Douglas and Richard Dreyfuss – wrote for the TV series B.L. Stryker (1989-90), starring Burt Reynolds, and got an Emmy nomination for one script. Urich returned as Spenser in four TV movies from 1993-95, with the Parkers writing some of the scripts, while three more TV movies featured Joe Mantegna as the detective.

None of this slowed Parker down – if anything, he became even more prolific. He completed Chandler's unfinished Marlowe novel, Poodle Springs (1989), and wrote a sequel to The Big Sleep called Perchance to Dream (1991), but neither was a real success. Another novel, All Our Yesterdays (1994), a multi-generational saga he thought his finest work, was highly praised but is probably his least known. In 1997 came a new hero, ex-baseball player Jesse Stone (Parker was a Boston Red Sox nutter), a police chief in Paradise, Mass., and two years later, Sunny Randall, created at the request of his friend, the Academy Award-winning actress Helen Hunt, who asked him to write a novel with a female investigator for a film which never got made. Eight more stories about Stone and five about Sunny followed.

With three nominations and two Edgar awards already to his credit, the Mystery Writers of America made Parker a Grand Master in 2002, and he was such an institution in Boston that tours of Spenser locations became popular with tourists. In publicity photos he posed "as Spenser" in a leather jacket, with a Red Sox baseball cap and Pearl the short-haired German pointer – there was a succession of dogs in his life called Pearl, not to mention a Welsh Corgi called Benni.

Later, he tried his hand at a series of westerns, one about Wyatt Earp in love called Gunman's Rhapsody, and Appaloosa, (2005) featuring Virgil Cole and Everett Hitch, which became a 2008 movie directed by and starring Ed Harris. Resolution (2008) and Brimstone (2009) followed, with Blue Eyed Devil still to come. Also in there somewhere were books about weightlifting and horse racing and even a pictorial guidebook to Spenser's Boston. Behind this torrent of words was a disciplined and immoveable work ethic: every day, five days a week, 50 weeks a year, he wrote five pages – even, I believe, while making cross-country promotion tours. It was on one of those that I first met him face to face. He was sitting at a table signing books and I walked up and said, "You don't look so tough to me." He looked up and grinned. "I am, though," he said.

And he was.

Frederick Nolan

Robert Brown Parker, writer: born Springfield, Massachusetts 17 September 1932; married 1956 Joan Hall (two sons); died Boston 18 January 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks